In this post, we look into the book “A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost“. Let us review and discover the soul of a Poet. Let us review A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost written in year 1913.

Let us explore: Themes in A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost and Analysis of A Boy’s Will.

Do you know that one of America’s greatest poets published his very first collection of poems when he was 39 years old? It is interesting to know that Robert Frost’s debut book “A Boy’s Will” (1913) wasn’t just a collection of verses – it was a spiritual autobiography that would establish him as one of the most beloved voices in American literature. When I read this remarkable collection, I am continuously amazed by how Frost masterfully weaves together themes of youth, isolation, nature, and the eternal human quest for meaning and connection.

Published in London by David Nutt in 1913, “A Boy’s Will” contains 31 poems that trace what Frost himself called “the story of five years” of his life. The title itself comes from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “My Lost Youth”: “A boy’s will is the wind’s will / And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts”. This collection would prove to be Frost’s literary breakthrough, earning praise from literary giants like Ezra Pound and William Butler Yeats, who declared it “the best poetry written in America in a long time”.

Keywords: A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost, A Boy’s Will, All 32 Poems in A Boy’s Will, Poems in A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost, Poems in A Boy’s Will

A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost (1913) – Discovering the Soul of a Poet | Book Review

Keywords: A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost, A Boy’s Will, All 32 Poems in A Boy’s Will, Poems in A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost, Poems in A Boy’s Will

The Genesis of Poetic Greatness ~ A Boy’s Will

It is interesting to know that Frost admitted much of the book was autobiographical, describing it as “pretty near being the story of five years” of his life. The title itself, borrowed from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “My Lost Youth,” suggests the wind-like nature of a boy’s will and the “long, long thoughts” of youth. This collection wasn’t just poetry—it was Frost’s emotional and artistic autobiography, chronicling a young man’s journey from isolation to connection, from uncertainty to understanding.

A farmer mowing a field with a scythe in a rural setting, reflecting the themes of Robert Frost’s poem ‘Mowing’ in ‘A Boy’s Will’

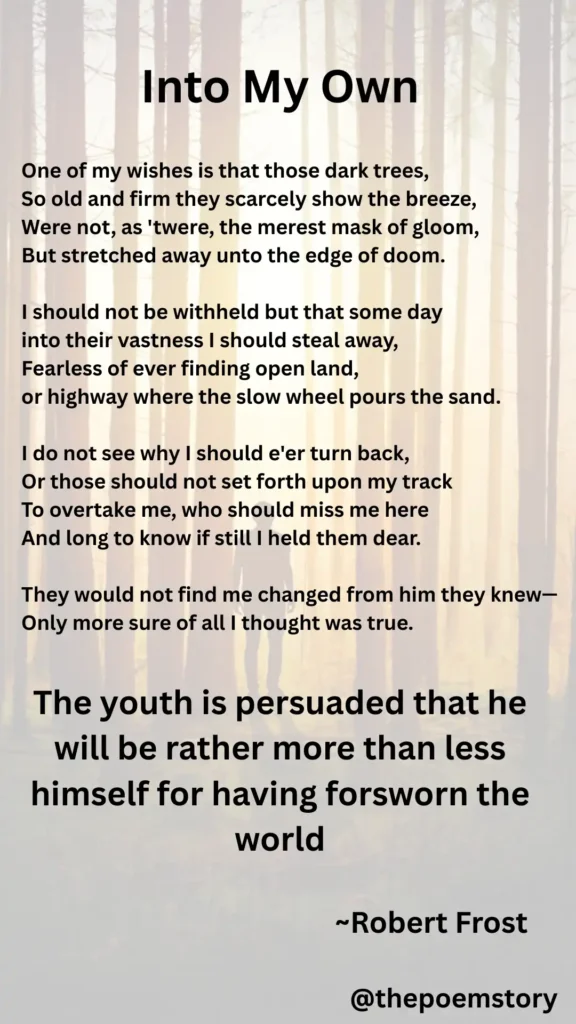

When I read his poem “Into My Own,” the opening piece of the collection, I am immediately struck by the fearless declaration of independence that would define Frost’s entire poetic career. The poem begins with an almost mystical longing:

“One of my wishes is that those dark trees,

So old and firm they scarcely show the breeze,

Were not, as ’twere, the merest mask of gloom,

But stretched away unto the edge of doom.”

This opening sonnet serves as both an invitation and a manifesto. The speaker yearns to “steal away” into the vastness of dark trees, “fearless of ever finding open land”. I love to read this poem again and again because it captures that universal moment of transition from youth to adulthood, that desire to venture into the unknown while maintaining one’s essential identity.

The Literary Architecture of “A Boy’s Will“ by Robert Frost: Understanding the Collection’s Structure

It is fascinating to discover that Frost organized his poems with remarkable intentionality. The collection is divided into three distinct parts, each representing a different stage of the speaker’s emotional and spiritual development. When I examine this structure, I see how brilliantly Frost crafted what scholars now recognize as a “spiritual autobiography” modeled after Tennyson’s “In Memoriam”.

A Boy’s Will – Part I: The Retreat from Society

The first section begins with the powerful opening poem “Into My Own,” where the young speaker declares his intention to withdraw from the world:

“One of my wishes is that those dark trees,

So old and firm they scarcely show the breeze,

Were not, as ’twere, the merest mask of gloom,

But stretched away unto the edge of doom.”

When I read these lines, I feel the restless energy of youth yearning to escape into the vastness of nature. The speaker continues: “I should not be withheld but that some day / Into their vastness I should steal away”. This poem establishes the central tension of the collection – the desire to forge one’s own path while maintaining connections to those we love.

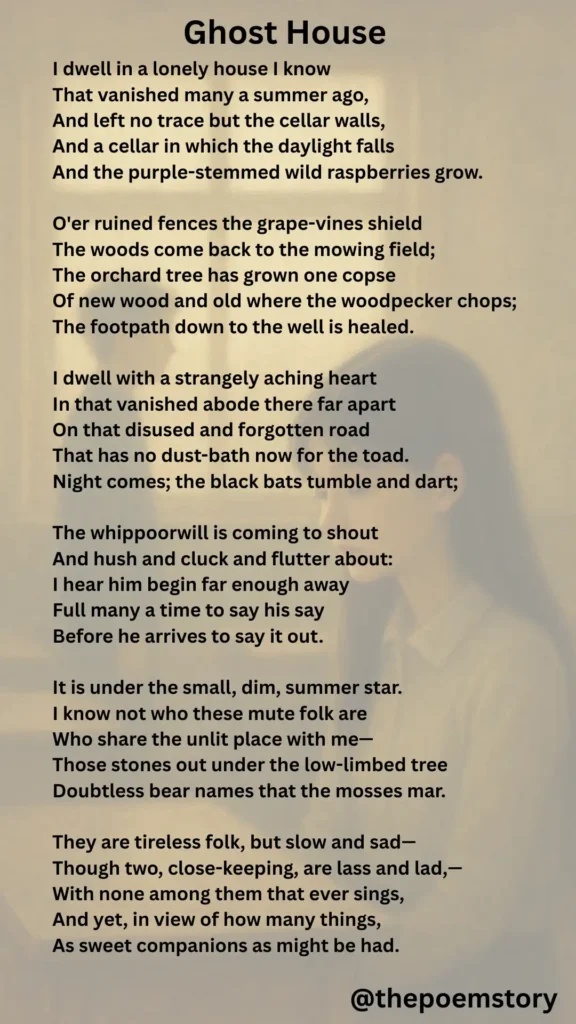

Following “Into My Own,” we encounter “Ghost House,” a haunting meditation on abandonment and isolation:

“I dwell in a lonely house I know

That vanished many a summer ago,

And left no trace but the cellar walls”

Do you feel the melancholy beauty in these lines? Frost’s speaker finds himself in a place where civilization has retreated, leaving only nature to reclaim what was once human habitation.

The Emotional Landscape: Key Poems of Part I

“My November Guest” – Embracing Melancholy

I love to read this poem again and again because of how Frost personifies sorrow as a companion who finds beauty in desolation:

“My Sorrow, when she’s here with me,

Thinks these dark days of autumn rain

Are beautiful as days can be”

It is remarkable how Frost transforms depression into a guide who teaches us to see beauty in barren landscapes. The speaker learns from his sorrow that “the love of bare November days” has its own profound beauty.

“Love and a Question” – The Moral Dilemma

This narrative poem presents a newly married man facing an ethical crisis when a stranger seeks shelter on a cold night. When I analyze this poem, I see Frost exploring the tension between personal happiness and moral obligation. The bridegroom must choose between protecting his intimate love and extending compassion to a stranger:

“But whether or not a man was asked

To mar the love of two

By harboring woe in the bridal house,

The bridegroom wished he knew.”

“Storm Fear” – Nature’s Threatening Voice

One of the most powerful pieces in the collection, “Storm Fear” reveals nature’s darker face:

“When the wind works against us in the dark,

And pelts with snow

The lower chamber window on the east,

And whispers with a sort of stifled bark,

The beast,

‘Come out! Come out!'”

This poem chills me with its portrayal of nature as a predator threatening the family’s survival. The speaker counts their meager strength: “Two and a child” against the overwhelming force of the storm.

A Boy’s Will – Part II: The Quest for Understanding and Connection

The second section marks a turning point where the speaker seeks to understand himself and his place in the world. This includes some of Frost’s most celebrated early work.

“The Tuft of Flowers” – Finding Brotherhood in Solitude

I am continually moved by this poem’s message of human connection transcending physical presence. The speaker goes to turn grass that another has mown, initially feeling profoundly alone:

“‘As all must be,’ I said within my heart,

‘Whether they work together or apart.'”

But then a butterfly leads him to discover flowers the previous mower has deliberately spared, revealing their shared aesthetic sensibility:

“The mower in the dew had loved them thus,

By leaving them to flourish, not for us,

Nor yet to draw one thought of ours to him,

But from sheer morning gladness at the brim.”

This discovery transforms everything. The speaker realizes: “Men work together, whether they work together or apart.” It is beautiful how Frost shows us that human connection can exist across time and space through shared values and appreciation of beauty.

“Mowing” – The Philosophy of Work

When I read “Mowing,” I hear the actual sound of the scythe through Frost’s masterful use of onomatopoeia. This sonnet explores the relationship between labor and meaning, suggesting that work itself can be a form of meditation and connection with nature.

A Boy’s Will – Part III: Acceptance and Wisdom

The final section shows the speaker gaining wisdom and preparing to re-engage with the world, culminating in “Reluctance.”

“Reluctance” – The Refusal to Surrender

The final poem of the collection serves as a powerful conclusion to the spiritual journey. After describing a landscape where autumn has given way to winter’s approach, the speaker asks:

“Ah, when to the heart of man

Was it ever less than a treason

To go with the drift of things,

To yield with a grace to reason,

And bow and accept the end

Of a love or a season?”

I find this conclusion deeply inspiring because it affirms the human spirit’s refusal to accept defeat, whether in love or in life’s natural cycles.

The Complete Catalog of A Boy’s Will: All 32 Poems in “A Boy’s Will”

Keywords: A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost, A Boy’s Will, All 32 Poems in A Boy’s Will, Poems in A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost, Poems in A Boy’s Will

For readers who want to explore each poem individually, here is the complete list of All 32 Poems in “A Boy’s Will” from the original 1913 edition:

Poems in A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost – Part I:

1. “Into My Own” – The youth is persuaded that he will be rather more than less himself for having forsworn the world

This opening poem is a sonnet about growing up and striking out alone. Do you know it’s about turning towards independence? Frost wrote it as a young man imagining the adult he will become. The speaker feels nervous excitement about entering his own world.

He pictures himself following a path into a dark forest, saying “I shall be telling this with a sigh” about choosing his way. The poem’s rich nature imagery – “quiet trees, and shimmering hills” – shows his anticipation of maturity. When I read this poem, I sense both the wonder and the anxiety of heading into the unknown. Frost reminds us that stepping out on our own is inevitable: “growing up is a mixture of anxiety and anticipation”

2. “Ghost House” – He is happy in society of his choosing

Ghost House captures the eerie loneliness of an abandoned home. It is interesting to know that scholars say this poem is “a meditation on the passage of time and the inevitability of loss”. Frost was living in a farmhouse when he wrote it, and he imagines its empty rooms haunted by memories. He writes about fairies and ghosts moving through the silence, turning a tumbledown house into a symbol for our own past. When I think of this poem, I picture an old parlor at twilight and feel the bittersweet sense that all houses – even people – eventually become memory. It encourages us to cherish the present before it, too, becomes a ghost.

3. “My November Guest” – He is in love with being misunderstood

In this poem, November itself becomes a companion. Frost personifies his sadness as a woman – “Sorrow” – who walks with him on a cold day. Do you know he talks directly to “her,” praising how even barrenness can be beautiful? As the poet says, she finds silver on the gray trees: “Simple worsted gray is silver now with clinging mist” (we see frost admiring November’s beauty). The speaker listens to Sorrow’s praise of the faded landscape.

I love this gentle, odd friendship: it’s as if Frost is telling us that even sorrow has its own joy. The poem shows we can learn to see beauty through pain. When I read it, the quiet November world feels full of mystery, and I remember that solitude and sadness sometimes bring unexpected solace.

4. “Love and a Question” – He is in doubt whether to admit real trouble to a place beside the hearth with love

In this poem, November itself becomes a companion. Frost personifies his sadness as a woman – “Sorrow” – who walks with him on a cold day. Do you know he talks directly to “her,” praising how even barrenness can be beautiful? As the poet says, she finds silver on the gray trees: “Simple worsted gray is silver now with clinging mist” (we see frost admiring November’s beauty). The speaker listens to Sorrow’s praise of the faded landscape.

I love this gentle, odd friendship: it’s as if Frost is telling us that even sorrow has its own joy. The poem shows we can learn to see beauty through pain. When I read it, the quiet November world feels full of mystery, and I remember that solitude and sadness sometimes bring unexpected solace.

5. “A Late Walk” – He courts the autumnal mood

This short lyric beautifully captures the last breaths of autumn. Frost writes in the voice of someone going out far too late in the year: he walks and finds every flower gone, birds flown, just a single aster to pluck. The line “I love to see the blue point of light / That beats against the falling snow” (in Frost’s own words) suggests the last golden flower he brings in. When I read it, I feel the chill of early winter and the lingering warmth of autumn. It’s a poem I love to read again and again because it captures the fleeting moment before winter’s hush, much like saving one beautiful bloom at the door of winter.

6. “Stars” – There is no oversight of human affairs

“Stars” paints a winter night sky where the stars shine solemnly on the snow. What’s remarkable here is how Frost emphasizes their indifference to us. The analysis notes these stars have “neither love nor hate,” just cold, “snow-white marble eyes without the gift of sight”. It is interesting to know that Frost portrays the stars as “beings onto themselves without humanistic qualities”. Reading this, I feel a mix of awe and loneliness: the stars are present, beautiful, yet not reacting to human life. Frost invites us to consider that nature’s grandeur simply is, apart from human emotions or concerns. It’s a contemplative, almost mystical piece about our place under the vast sky.

7. “Storm Fear” – He is afraid of his own isolation

This poem is a fierce, tense scene. A father tends his wife and baby inside their cabin as a blizzard howls outside – the storm is likened to a wild beast at the door. Frost himself experienced such storms and channels real fear: he imagines the wind pelting the roof and chases his children to safety. As one commentator notes, “a violent winter storm haunts a rural family, symbolizing both real danger and emotional struggle”. When I read “Storm Fear,” my heart races. I can almost hear the wind’s howl in the poetry. It’s a dramatic reminder of how small we are against nature’s fury and how courage emerges in the hearth of home.

8. “Wind and Window Flower” – Out of the winter things he fashions a story of modern love

Do you ever feel like your love is just out of reach? In this allegory, Frost sets up a winter wind and a bird-in-a-cage (the “window flower” on a sill). The cold breeze tries with all its force to reach the flower, but the glass holds it back. Analysts say the wind is cold and powerless, and the flower is trapped and oblivious.

I love how Frost shows unrequited love: the wind sighs and shakes at the window, but the flower only notices after the wind has given up. When I read it, I feel a tender sadness. It’s a conversation in symbol: Frost seems to say sometimes love goes unrecognized, leaving a kind of regret. Yet it’s so nicely told with everyday images of a windy day and a caged bird.

9. “To the Thawing Wind” – He calls on change through the violence of the elements

Frost turns to spring in this poem, almost like giving a pep talk to the warm winds. He joyfully calls the south wind to come thaw the snows and wake the flowers. The imagery is lively: melting frost, birds awakening, “buried flower” rising up. According to critics, Frost even suggests that this thawing storm can rouse the artist himself: a playful line hints the wind might “turn the poet out of door” – implying creativity needs a little turbulence. When I encounter this poem, I’m energized: it’s hopeful chaos, the kind that precedes spring renewal. Frost captures the excitement of change – urging us to welcome disruption because it brings new life.

10. “A Prayer in Spring” – He discovers that the greatness of love lies not in forward-looking thoughts

Here Frost gets simple and sincere. The speaker offers a prayer – not for rain or harvest, but for the gift of enjoying today. He asks only to be thankful and peaceful right now. As one analysis notes, he asks for “pleasure in the flowers to-day” and joy with the bees, rather than fretting tomorrow’s problems. This poem is so lovely because it feels humble: instead of seeking grandeur, the speaker just wants contentment. I often repeat its lines to myself on hectic days: it reminds me to pause, smell the flowers, and find gratitude in the present moment. Frost shows that sometimes “asking for roses” is enough by itself.

11. “Flower-gathering” – nor yet in any spur it may be to ambition

This charming poem is like a snapshot of domestic love. A man plans an early morning walk to pick flowers, and his wife asks to join. He gently tells her to wait home, promising “the flowers to seek and bring” from the fields. It’s sweetly mysterious whether he literally means flowers or the poems he creates for her. What stands out is the tenderness: he says their separation, however brief, makes the hours feel like “ages” apart. I love the sincerity in it – it celebrates small acts of devotion (gathering flowers, writing verse) and how even a short outing can feel long when someone you love is waiting.

12. “Rose Pogonias” – He is no dissenter from the ritualism of nature

Now Frost paints a hidden sanctuary. In a hot afternoon they find a secluded glade where rare orchids (pogonias) bloom. He and his friend bow in wonder at the “sun-shaped, jewel-small” blooms and pluck a few. The poem even has them raise “a simple prayer” hoping the mower will miss that spot. It is interesting to know that the orchid meadow here feels almost sacred, a precious ‘treasure-house of the sun’ that they dare not lose. When I read it, I feel transported to that secret circle of wildflowers. It celebrates the fleeting beauty we stumble upon – and our instinct to protect it. Frost’s quiet reverence makes me want to honor those little pockets of beauty in nature.

13. “Asking for Roses” – nor from the ritualism of youth which is make-believe

In this pastoral poem, Frost illustrates carpe diem through flower imagery. A couple finds an old house with blooming roses and wonders if it’s rude to gather a few. They gather courage, knock at the echoes of silence, and silently beg “for roses”. As critics note, Frost uses it to say nothing is gained by not taking beauty when you can. This has always felt like a gentle life lesson to me: why stand on ceremony when simple joys are within reach? I love the hopeful tension of the scene – will the roses be denied, or generously given? It ends with that affirmation: “that be not denied!” – a line that encourages us to embrace life’s petals while we may.

14. “Waiting Afield at Dusk” – He arrives at the turn of the year

This quiet poem shows a lone figure in a harvested field at dusk. Frost’s language is peaceful: twilight birds, dry grass, a harvest done. As night falls, the speaker thinks of a loved one who’s far away. It’s an intimate moment of longing. Do you know Frost often sets longing against nature’s calm? Here the tranquil scene makes the speaker’s memories of love even sharper – it ends feeling as if the stars and the bats witness his tender mood. Reading it, I feel serene yet poignantly aware of absent friendship or love. It’s a reminder that in stillness, our hearts often become most active.

15. “In a Vale” – Out of old longings he fashions a story

This is a dreamy, nostalgic piece. Frost looks back to a marshy valley of childhood. He mentions “misty fen” and “strange and sad” maidens who once guided him. Analysts say these “pale maidens” gave him secret knowledge of nature’s workings. The poem claims he alone “knows why the flower has odor, the bird has song” thanks to them. It’s whimsical and mystical – like a fairy tale memory. When I think about it, I picture Frost as a boy by a misty creek, learning nature’s mysteries. It reads as if life’s wonder was given in those nights, and I find the tone almost like a lullaby for lost youth.

16. “A Dream Pang” – He is shown by a dream how really well it is with him

Frost turns to longing again here, but in an almost playful way. The poem describes the speaker walking in woods singing, when someone appears and hesitates at the edge – perhaps a lover or friend. Neither crosses the threshold, and both slip away. In the last lines Frost speaks of the “sweet pang” of that lost meeting. It’s a delicate, bittersweet piece: after reading it, I feel the ache of missed chance. It captures the feeling of catching sight of someone across a park and then the moment evaporating. Frost leaves us with that residual pang – a quiet sorrow that lingers when something beautiful almost happened.

17. “In Neglect” – He is scornful of folk his scorn cannot reach

Here Frost explores abandonment wryly. He starts, “They leave us so to the way we took,” meaning friends or society give up on the speaker and his companion. Left “in a wayside nook,” they even try to “feel forsaken”. But then Frost notes the twinkle in their eye – “mischievous, vagrant, seraphic” – as if they sort of enjoy their outcast freedom.

I find this poem curiously uplifting.

It says: even if people disregard you, you can carry on with a sort of defiant contentment. It’s about making light of neglect – taking control of your solitude. When I read it, I feel a bit of that mischievous pride Frost describes, as if saying “No, I won’t just feel sorry – life goes on.”

18. “The Vantage Point” – And again scornful, but there is no one hurt

This poem plays with perspective. The narrator seems to be a wild creature on a hilltop, watching humans below. He tires of mankind’s bustling world and looks down to see flowers – “Bluets” (tiny blue flowers) – springing on the hillside. From this high “vantage point,” he notes humans look as small as ants. It’s clever: Frost imagines nature’s eye looking at us.

When I read it, I feel a playful humility. It reminds us that from the big picture (or nature’s view), our troubles shrink. Frost encourages us to step back sometimes – he literally climbs a hill to do just that. The final image of towered flowers vs. ant-like people gives me a smile and a sense of balance between humanity and the natural world.

19. “Mowing” – He takes up life simply with the small tasks

This simple yet rich poem shows a farmer happily working alone. Frost himself once wrote about hearing nothing but the sound of his scythe. The speaker listens to his scythe’s hiss in the field, and imagines it whispering a secret. He jests that the only listener is himself – no faeries or muses are needed; the truth of honest work is enough.

One key line is: “And that has made the sound forsaken / Of answering something almost gone” – meaning the scythe’s song is pure truth, “no message but the dream of the world”. To me, it’s a celebration of labor’s satisfaction. When I read “Mowing,” I’m soothed by its rhythm, feeling that Frost admires the peace and meaning found in simple toil. We don’t need myths – just mindful work under the sky, Frost seems to say.

Poems in A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost – Part II:

20. “Going for Water” – He resolves to become intelligible, at least to himself

A charming, adventurous piece! The well is dry, and the children are eager to fetch water from a brook. But Frost shows they love the task: they run joyfully “because the autumn eve was fair,” the woods were theirs, and there was excitement in the quest. This poem reminds us that even chores become fun when done with a sense of freedom.

It’s interesting how Frost says any task can be enjoyed in nature. Reading it makes me smile – the young speakers treat the simple errand as an outing. I love how Frost finds magic in everyday moments. “Going for Water” teaches that happiness often depends on attitude: an errand can be uplifting if we carry a sense of wonder.

21. “Revelation” – and to know definitely what he thinks about the soul

This poem feels more philosophical. Frost begins, “The world was already the world / and we were looking for ourselves,” which captures the universal search for identity. The central image is tying our names like “slices of concrete… to our feet for security” – as if we need heavy anchors (names, stories) to feel grounded. It suggests these anchors are more burden than help.

As the poem continues, Frost moves from stories of folks gone missing to a strangely political finish. He concludes by implying true revelation comes in simple human moments – “the light in her smile, or the… moment she touched his hand” – rather than from power or intellectual games. When I dive into “Revelation,” I feel Frost’s urge to find meaning in small human connections. It reads as if he asks, are we too busy building concrete anchors to see the real light around us?

22. “The Trial by Existence” – about love

This is a grand, mystical poem – much more epic than Frost usually writes. It depicts souls on a cosmic journey: they awaken “to find valor reign… not dissemble their surprise”. In other words, even brave people are amazed to see heroism rewarded after death. The poem speaks of a heavenly trial for souls, where earthly deeds are measured. It says that once a soul enters this fate, it remembers nothing of choice – indicating a surrender of ego. Frost even compares it to Dante’s vision.

One memorable line is: “the utmost reward of daring should be still to dare”, implying eternity offers yet more courage. Honestly, reading this fills me with awe and a touch of mystery. The Trial by Existence stretches beyond Frost’s usual farm fields; it shows his philosophical side – wondering what life, and afterlife, really mean.

23. “In Equal Sacrifice” – about fellowship

In this lesser-known piece, Frost retells a Scottish legend. It recounts Sir James Douglas carrying the heart of his king (Robert the Bruce) to battle. Douglas says “heart or death!” and leaps into the fight. Frost uses this tale to highlight ultimate loyalty and self-sacrifice. The closing lines encourage the reader: “So may another… Give a heart to the hopeless fight… In equal sacrifice”. It’s stirring and almost patriotic. When I read it, I feel transported to the crusades: it’s dramatic and inspiring, showing Frost’s interest in nobility of spirit. This poem stands out in the collection as a historical narrative – it’s about courage being passed on to others who will fight “with the heart he bore.”

24. “The Tuft of Flowers” – about death

One of Frost’s best-loved early poems! A mower finds himself after a neighbor’s left the field. For a while he feels alone – “I must be, as he had been, alone”. But a butterfly floats by, leading him to a bright tuft of flowers spared by the other man’s scythe. Suddenly the mower realizes: “the mower in the dew had loved them thus, by leaving them to flourish”.

In that moment, he feels a bond with the absent farmer. Frost calls it a “message from the dawn” that connects them through nature. When I read this, it’s like sharing a smile with someone far away. It’s mystical yet simple: even if people aren’t physically together, they can share love for nature. This poem has always given me hope that human connection can appear in unexpected ways – even in a cleared field of flowers.

25. “Spoils of the Dead” – about art (his own)

A haunting and unusual poem. Frost imagines little fairy-boys playing on a corpse, amused by the “glittering things” (a ring and chain) they find. The tone shifts sharply when the speaker interrupts: he hates the faeries’ naive joy. He says he recognized death with sorrow and dread when he saw the dead man. Essentially, Frost contrasts innocent ignorance with human grief. It makes me shiver: the fairies take worldly objects from death as toys, while Frost’s speaker mourns what’s truly lost. After reading this, I feel the weight of mortality. It’s a powerful meditation on how different beings encounter death – with innocence or sorrow. Frost leaves us pondering: do we approach loss naively or empathetically?

26. “Pan with Us” – about science

This whimsical poem brings the Greek god Pan to a New England hillside. Pan, gray and rugged from the woods, stands under the sun playing his pipes for nature. But he sees no smoke, no houses – humanity has left this wild place. Frost writes that the world has “found new terms of worth” and Pan’s old music “kept less of power” now. Finally Pan flings down his pipes, lying on the earth and wondering, “Play? Play? – What should he play?”.

Reading this, I feel a gentle sadness: the old ways of nature’s music have no audience. It’s an evocative commentary: sometimes progress and change can leave even mythical spirits feeling out of place. I find it beautifully lonely – Pan finds peace again with nature’s own sounds (the birds, the wind) instead of human ears.

27. “The Demiurge’s Laugh”

This short poem is a quiet blow to self-delusion. The speaker chases a “Demon” that he thinks might be some hidden truth. But Frost immediately notes “what I hunted was no true god” – he was pursuing an illusion. In the end the “Demon” laughs at him, half sleepy and half mocking. The idea is that sometimes we passionately chase false idols or answers that turn out to be nothing. Frost is saying: we often follow shadows of our own making.

After reading it, I felt humbled and thoughtful. It’s like Frost gave me permission to laugh at myself when I realize something I sought so hard was maybe just wishful thinking. The poem’s final resignation (sitting alone under a tree) perfectly captures the feeling of letting go of a fool’s errand.

Poems in A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost – Part III:

28. “Now Close the Windows” – It is time to make an end of speaking

This poem has a tone of quiet resignation. The speaker literally tells winter to stop: “Now close the windows and hush all the fields” – shut out the noisy world. No birds, no wind sounds; let the cold beauty lie undisturbed. The analysis points out that he’s preparing for solitude, for a long silence before spring. Interestingly, the last line asks us to “see all wind-stirred” while not hearing it – as if experiencing the world internally rather than through raw sound. When I read this, I feel the stillness and a sense of inner focus.

It’s contemplative: Frost seems to be accepting that winter is here, and instead of battling it, he chooses to turn inward. It’s melancholic but also oddly comforting – like snuggling under a warm blanket of thought while the world sleeps outside.

29. “A Line-storm Song” – It is the autumnal mood with a difference

This is a passionate poem of love facing adversity. The speaker describes a wild storm raging around, then repeatedly invites his love to “Come… and be my love in the rain”. Each stanza paints storm clouds, wet roads, shattered flowers, and then he says: no matter the wind or darkness, her presence is what he wants. It’s like saying: if love is a refuge, let it flourish even amid storm. I love this piece because it’s both romantic and optimistic: he acknowledges “All song of the woods is crushed” by the storm, yet still calls her to embrace it with him.

The rain becomes a symbol – of trials – and he says he doesn’t mind getting “wet-shod” if she stands with him. It’s an adventurous, beautiful call to perseverance in love. When I read it, I imagine dancing together in the rain, come what may.

30. “October” – He sees days slipping from him that were the best for what they were

Ode to October! Frost’s words are like a prayer to a perfect autumn day. “O hushed October morning mild,” he begins, savoring the mellow quiet and colors. He begs the day to “Begin the hours of this day slow.” Every line says: slow down, let me enjoy this. He even asks for one leaf to fall at dawn, another at noon – “Slow, slow!” – so that even the grapes’ last ripening won’t be ruined by frost. An insightful commentary on the poem observes that Frost might be speaking as someone in life’s autumn years: enjoying one’s harvest while wanting time to stretch.

Indeed, I read this with a very bittersweet feeling – the beauty is rich, yet ephemeral. It has become one of my favorites for its perfect mix of hope and resignation, celebrating the best things in life and the wish that they’d linger just a moment longer.

31. “My Butterfly” – There are things that can never be the same

A very personal elegy, this poem mourns something precious. Here Frost addresses a butterfly, now dead, in heartbreak. The imagery is vivid: he recalled the butterfly dancing in sunlight (like a fairy-tale flower) and then finds a broken wing among the leaves. The poem is about the shock of realizing beauty can vanish. It portrays a quiet, intimate loss – perhaps of a child or cherished friend – through the butterfly symbol. When I read this poem, it feels like someone is softly crying.

Yet it also gently reminds us: everything beautiful in life is fleeting. Frost’s lush descriptions of the butterfly’s flight (“tossed, tangled, whirled… in love”) make the final discovery all the more poignant. It’s bittersweet: a reminder to treasure each moment, because “nothing lasts forever.”

32. “Reluctance” – The final acceptance and refusal to surrender

Finally, Reluctance feels like Frost’s own farewell to youth and summer. The speaker wanders back home but finds his world winter-worn: “The leaves are all dead on the ground,” and his fields are bare. It’s as if life’s vibrancy has ended. However, instead of surrendering, Frost ends with defiance: “Was it ever less than a treason… To bow and accept the end of a love or a season?”. He argues that one must fight for what they value – not quietly yield to change. It’s an inspiring stance on endings. When I read it, I’m struck by that final question – it makes me want to resist giving up, whether in nature or love.

Frost doesn’t let autumn just take our hearts; he reminds us to hold onto wonder a little longer. It’s a powerful, determined close to the collection, urging us to cherish beauty and strive for it.

Each of these poems in A Boy’s Will shows a facet of Frost’s early genius – from the dew of morning lawns to the darkness of old houses, from youthful longing to bold legends. I hope this brief tour has whetted your appetite to read them yourself. Frost’s writing is conversational and rich with nature, so remember you can almost hear him speaking to you. And if these glimpses moved you, don’t miss our full Biography of Robert Frost: The Voice of Rural America and the Heart of Modern Poetry on our site. It will lead you deeper into Frost’s life and works. Happy reading – and watch for frost under your feet as you go!

The Literary Achievement: Why “A Boy’s Will” Matters

It is remarkable to consider that this collection established virtually every major theme that would define Frost’s career. When critics examine this work, they note how it introduced Frost’s characteristic voice – deceptively simple yet philosophically complex, rooted in New England rural life yet addressing universal human concerns.

The poems in “A Boy’s Will” differ radically from the late 19th-century Romantic verse with its “ever-benign view of nature”. Instead, Frost presents nature as complex and sometimes threatening, wearing “two faces” – sometimes healing, sometimes dangerous.

Contemporary critics immediately recognized the collection’s significance. F.S. Flint praised Frost’s “ear for silences” and his ability to achieve “direct observation of the object and immediate correlation with the emotion”. Lascelles Abercrombie warned that the simplicity of Frost’s language didn’t imply simplicity in his poetry – rather, “the selection and arrangement of the substance do practically everything”.

The Biographical Context of Poems in A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost: Art from Life

Keywords: A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost, A Boy’s Will, All 32 Poems in A Boy’s Will, Poems in A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost, Poems in A Boy’s Will

When we learn that Frost admitted the book was highly autobiographical, covering “the story of five years” of his life, we begin to understand the emotional authenticity that makes these poems so powerful. The collection draws heavily from Frost’s experiences on a thirty-acre farm in Derry, New Hampshire, where he lived for ten years before moving to England.

It is particularly moving to know that many scholars interpret the collection as mourning not just the rural life Frost had left behind, but also grieving for his eldest child, Elliott, who died of cholera at age three in 1900. This biographical context adds profound depth to the collection’s pervasive atmosphere of loss and longing.

The Technical Mastery in Poems in A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost: Form and Sound

What continues to amaze me about Frost’s technique is how he perfected what he called “the sound of sense” – “the abstract vitality of our speech…pure sound—pure form”. In poems like “Mowing,” we literally hear the swishing of the scythe; in “Storm Fear,” we feel the wind’s threatening whisper.

The poems employ various forms – sonnets, quatrains, heroic couplets – but always in service of meaning rather than mere technical display. Frost’s innovations in capturing natural speech rhythms within traditional meters would influence generations of poets.

Legacy and Influence of Poems in A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost: The Foundation of Greatness

Looking back over a century later, we can see how “A Boy’s Will” established the foundation for everything that followed in Frost’s career. From this first book came anthology staples like “Storm Fear,” “The Tuft of Flowers,” and “Mowing”. The themes explored here – the relationship between solitude and community, the complexity of moral choice, the healing and threatening aspects of nature – would be developed throughout his subsequent collections.

It is worth noting that without “A Boy’s Will,” Frost could not have gone on to write the “large number of immortal poems of the later books”. This collection proved that an American poet could achieve international recognition while remaining true to distinctly American experiences and landscapes.

Reading “A Boy’s Will” Today: An Invitation

As I conclude this exploration, I encourage you to read “A Boy’s Will” not just as a historical artifact, but as a living document of the human experience. These poems speak to anyone who has ever felt the tension between belonging and independence, who has found solace in nature’s beauty while acknowledging its indifference, who has struggled with moral choices that have no clear answers.

Each poem in this collection deserves individual attention and analysis. In future posts, I will be diving deep into each of these 31 remarkable poems, exploring their individual themes, techniques, and meanings. I invite you to join me on this journey through one of American literature’s most significant debut collections.

Do you feel the same sense of wonder that I do when reading Frost’s work? These poems remind us that the questions of youth – about identity, purpose, love, and mortality – never truly leave us. They simply evolve as we gain experience and wisdom.

It is my hope that this exploration of “A Boy’s Will” will inspire you to seek out not just Frost’s complete works, but to explore the rich tradition of American poetry that he helped establish. For more insights into Frost’s life and work, I encourage you to read my biography piece: Biography of Robert Frost: The Voice of Rural America and the Heart of Modern Poetry.

When you next find yourself in a moment of solitude in nature, remember Frost’s young speaker discovering that butterfly and those spared flowers. Remember that even in our apparent isolation, we are connected to all those who have shared our appreciation for beauty, our questioning of existence, and our reluctance to accept easy answers to life’s profound mysteries.

The boy’s will may be the wind’s will, but in Frost’s masterful hands, that restless energy becomes the foundation for a lifetime of poetic achievement and a body of work that continues to speak to readers more than a century after its first publication.

Keywords: A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost, A Boy’s Will, All 32 Poems in A Boy’s Will, Poems in A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost, Poems in A Boy’s Will, A Boy’s Will analysis, Robert Frost A Boy’s Will, A Boy’s Will poems analysis, Robert Frost poetry collection, Into My Own Robert Frost, The Tuft of Flowers, Mowing poem Robert Frost,

My November Guest meaning, Robert Frost poem summary, Wind and Window Flower analysis, Nature poems by Robert Frost, Early poetry Robert Frost, American poetry classic, Modernist poetry America, Best poems by Robert Frost, Biography of Robert Frost, Rural life in poetry, 1913 poetry collections, Frost’s first book, Spiritual journey poetry, Youth and self-discovery poems, Themes in A Boy’s Will by Robert Frost, Symbolism in Robert Frost’s poems, Nature and isolation in Frost poetry, Analysis of A Boy’s Will, Famous Robert Frost poems, American modern poetry, Poem meanings Robert Frost, Literary criticism Robert Frost.