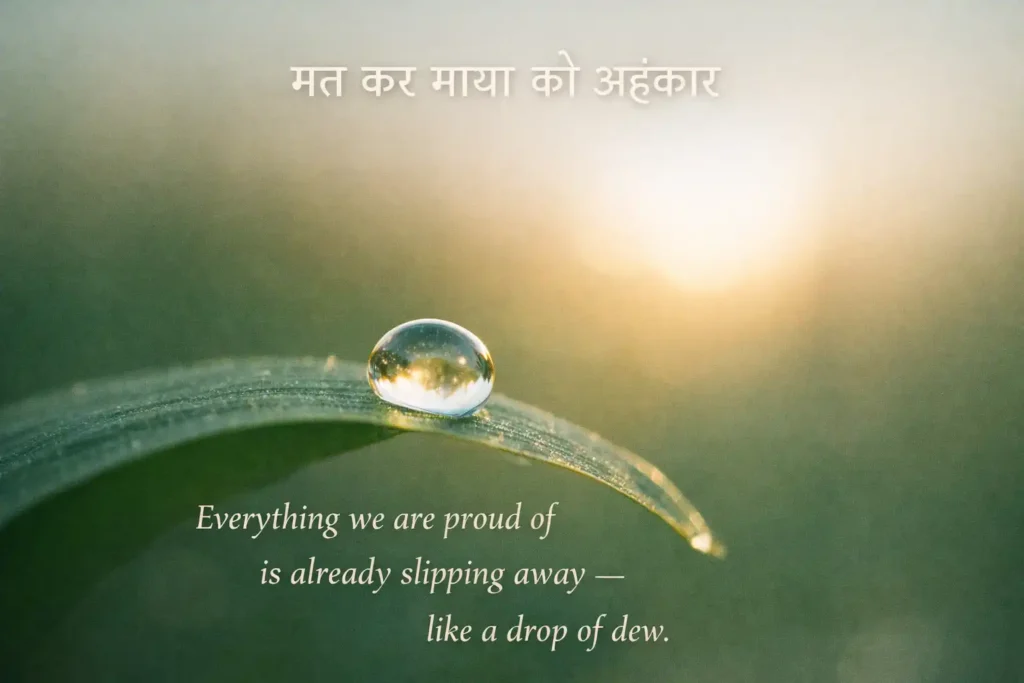

Indian devotional poetry has a unique way of confronting the deepest human illusions — not through fear, but through quiet clarity. Mat Kar Maaya Ko Ahankar is one such traditional bhajan. It does not shout warnings or threaten punishment. Instead, it gently reminds us of a truth we often forget: nothing we cling to is permanent.

“Everything we are proud of is already slipping away — like a drop of dew.”

In a world obsessed with identity, achievement, wealth, and the body itself, this bhajan asks uncomfortable questions. What remains when power fades? What survives when the body fails? What is truly ours?

Using simple metaphors — clay, wind, a lamp, and a drop of dew — the bhajan dismantles ego layer by layer, finally pointing toward liberation through wisdom and grace.

Read More in Poetry Section

Mat Kar Maaya Ko Ahankar

Original Hindi Lyrics: Mat Kar Maaya Ko Ahankar

मत कर माया को अहंकार,

मत कर काया को अभिमान,

काया गार से काची।ओ काया गार से काची,

हो जैसे ओस रा मोती,

झोंका पवन का लग जाए,

झपका पवन का लग जाए,

काया धूल हो जासी।ऐसा सख्त एक महाराज,

जिसका मुल्कों पे राज,

जिन घर झूलता हाथी।

जिन घर झूलता हाथी, उन घर दिया ना बातीझोंका पवन का लग जाए,

झपका पवन का लग जाए,

काया धूल हो जासी।खूट्यो सिन्दड़ा रो तेल,

बिखर गयो सब निज खेल,

बुझ गयी दिया की बाती।झूठा माई थारो बाप,

झूठो सकल सब परिवार,

झूठी कूटता छाती।बोल्या भवानी हो नाथ,

गुरु ने जो सर पे धरया हाथ,

जिनसे मुक्ति हो जासी।

English Translation: “Like a Drop of Dew”

Do not be deluded by Maaya,

Do not take pride in the body.

It is fragile like unfired clay,

Like a trembling drop of dew.A single breath of wind,

The faintest passing gust,

And the body turns to dust,

Vanishing like a drop of dew.There once was a stern king,

Renowned across many lands;

Elephants swayed in his royal court —

Now there is no lamp at that royal courtA single breath of wind,

The faintest passing gust,

And the body turns to dust,

Vanishing like a drop of dew.The clay lamp was filled with oil,

From it this worldly play arose;

The flame burned bright within the lamp,

Shining like a drop of dew.When the oil was finally spent,

The play of life fell apart;

The lamp went dark, the flame was gone,

Extinguished like a drop of dew.Mother and father — illusion.

Family bonds — illusion.

Tears and beating of the chest — illusion,

All dissolving like a drop of dew.Says Bhavani Nath:

“My Guru placed his hand upon my head.

Through that grace, liberation is mine.”

Line-by-Line Meaning of Mat Kar Maaya Ko Ahankar and Philosophical Interpretation

1. Do Not Be Proud of Wealth or the Body

The bhajan begins by dismantling two illusions that form the foundation of human ego: maaya, the sense of ownership over wealth and worldly success, and kaya, the belief that the body is a permanent and reliable identity. Both appear stable because they stay with us for long stretches of life, long enough for the mind to mistake continuity for permanence. Yet neither is truly ours.

Wealth is not created in isolation. It flows through circumstances, inheritance, opportunity, social structures, and sheer chance. What arrives through conditions can depart when those conditions change. A single decision, a market shift, illness, or time itself can erase years of accumulation. The bhajan does not condemn wealth; it exposes the illusion of control we attach to it.

The body is an even subtler illusion. Because we inhabit it every moment, we confuse presence with possession. We speak of the body as “mine,” yet we have no authority over its aging, its illnesses, or its final collapse. Strength fades, senses dull, memory fractures — all without our consent. The bhajan reminds us that the body is not an achievement, but a temporary instrument.

From these misunderstandings arises pride. Ego is born not from what we have, but from the belief that what we have is secure. When wealth or youth is mistaken for permanence, identity hardens around it. The bhajan quietly breaks this rigidity by pointing to time — the one force that does not negotiate.

By exposing wealth and the body as borrowed, the bhajan offers a liberating insight: that which is impermanent cannot define the self. What truly belongs to us must remain when possessions fall away and the body itself returns to dust. Everything else, no matter how intimate or impressive, is only passing through.

“The body stays long enough to deceive us,

wealth shines long enough to blind us,

and time arrives quietly to return both to dust.”

2. The Body as Fragile Clay

The comparison of the human body to raw clay is neither poetic exaggeration nor pessimism — it is a precise observation. Clay can be molded into countless forms, admired for its shape and function, yet it remains fundamentally fragile. Until it is fired, it carries no lasting strength. A single impact is enough to shatter it. In the same way, the body appears resilient only while conditions remain favorable.

Health gives the illusion of permanence. Routine masks vulnerability. As long as pain is absent and energy flows freely, we assume continuity. But the bhajan reminds us that the body’s strength is conditional, not inherent. Illness, accident, or the quiet erosion of time can dismantle it without warning. What seemed reliable suddenly reveals its limits.

This imagery is not offered to provoke fear or despair. Fear arises from attachment; understanding dissolves it. By recognizing the body as clay rather than stone, arrogance loses its foundation. Pride in appearance, strength, or youth fades when we see the body as a temporary vessel rather than a permanent identity.

The bhajan does not ask us to reject the body, but to relate to it truthfully. When the illusion of durability is removed, care replaces pride, humility replaces vanity, and gratitude replaces entitlement. In this clarity, the body is no longer a source of ego — it becomes a reminder of impermanence and a teacher of restraint.

“Clay does not fail us;

it simply reminds us that we were never meant to last.”

3. The Drop of Dew: Beauty Without Permanence

The image of a drop of dew lies at the very heart of the bhajan’s vision. Dew is not ugly, weak, or insignificant. It is luminous, pure, and quietly enchanting. Resting on a leaf at dawn, it mirrors the vastness of the sky within its fragile surface. For a brief moment, it seems complete, self-contained, and perfect.

Yet its beauty exists only because of its impermanence. The same sun that reveals the dew’s brilliance also dissolves it. There is no violence in its disappearance, no struggle, no resistance — it simply vanishes when conditions change. The bhajan chooses this image deliberately, not to suggest tragedy, but to illustrate truth without bitterness.

Human life follows the same pattern. Youth glows for a while, achievements sparkle, power appears commanding, and identity feels whole. But like dew, these forms depend entirely on circumstance. Time, change, and decay are not external enemies; they are intrinsic to the design. What shines is already passing.

By repeating this metaphor, the bhajan trains the mind to see beauty without clinging. It does not urge rejection of life’s brightness; it urges recognition of its nature. The dew teaches us how to admire without possessing, how to celebrate without demanding permanence. In doing so, it transforms beauty from a source of attachment into a doorway to understanding.

“We suffer not because beauty fades,

but because we demand that it stay.”

4. Power and Kingship Are Also Temporary

The bhajan then turns its gaze toward worldly authority, the most seductive and convincing form of ego. Power, more than wealth or the body, creates the illusion of permanence because it reshapes the world around it. A king ruling over nations, commanding armies, and living amidst elephants — the ultimate symbols of royal strength and dominance — appears untouchable, insulated from ordinary human fragility.

Yet the bhajan places this image alongside the same truth it applies to all things: authority, too, is temporary. History bears silent witness to this fact. Empires that once dictated the fate of continents now exist only as broken stone and fading names. Palaces crumble, thrones vanish, and the memory of absolute power dissolves into archaeological footnotes.

What makes this insight powerful is its restraint. The bhajan does not mock kings, nor does it rage against power. It simply observes that time recognizes no hierarchy. Crowns and commands hold no authority over decay. The same wind that reduces a fragile body to dust also erases the mightiest reign.

In asserting that power does not negotiate with time, the bhajan offers a sober clarity: authority may control others, but it cannot control impermanence. The moment this truth is seen, domination loses its illusion of eternity, and humility becomes unavoidable.

“Power can command the world,

but time commands power.”

5. The Clay Lamp and the Illusion of Continuity

Life is compared to a clay lamp, an image both intimate and precise. The lamp is humble, easily overlooked, yet central to the unfolding of light. Its flame appears steady, even dependable, but it survives only as long as the oil allows. The bhajan uses this image to remind us that life, too, runs on a finite reserve.

While the oil lasts, the flame burns and the “play” continues. We assume roles, build relationships, pursue ambitions, and construct identities. The continuity of the flame creates the illusion of stability. Day after day, the light persists, and we begin to believe it always will. The play feels complete, as though it has a guaranteed ending written into it.

But when the oil is exhausted, the flame does not negotiate. It does not linger for closure, nor does it wait for final conversations. The play collapses in an instant. Projects remain unfinished. Words remain unspoken. Departures are unannounced. Life does not conclude — it simply stops.

This observation is not meant to darken the heart. It is not pessimism, nor a denial of meaning. It is realism stripped of comforting illusions. By seeing life as a borrowed flame rather than a permanent light, urgency replaces complacency, presence replaces postponement, and sincerity replaces performance. The lamp teaches us not to despair, but to pay attention while the light is still burning.

“What matters is not how long the flame burns,

but how attentively we live in its light.”

6. Death and the Shattering of Attachment

When the bhajan refers to parents, family, and even mourning as “illusion,” it is not rejecting love, nor diminishing human bonds. Instead, it draws a crucial distinction between love and permanence. Love is real, deeply human, and transformative. What is illusory is the belief that these relationships can escape time and loss.

Attachment becomes suffering not because we care, but because we demand eternity from what is inherently temporary. We do not grieve only the person we lose; we grieve the collapse of the future we assumed would exist. Death shatters not just bonds, but expectations — and it is this rupture that causes unbearable pain.

The bhajan’s language may sound severe, but its intention is compassionate. By naming family ties as illusion, it exposes the hidden contract we unconsciously sign: that those we love will always remain, unchanged and available. When reality breaks that contract, the heart experiences shock.

The bhajan does not instruct us to withdraw from love or suppress grief. It invites us to love without the illusion of possession, to grieve without the demand for permanence, and to accept loss without resentment toward existence itself. In this clarity, love becomes purer, less fearful, and more spacious — no longer chained to the impossible promise of forever.

“Grief hurts not because love ends,

but because permanence was expected.”

7. Guru and Liberation: The Turning Point

The final verse marks a decisive turning point. After repeatedly invoking images of fragility — clay, wind, dew, extinguished flame — the bhajan deliberately abandons all metaphors of impermanence. The familiar refrain disappears. Liberation is no longer compared to a drop of dew, because liberation does not dissolve. It does not fade, scatter, or vanish. What is eternal requires no fragile imagery.

At this moment, the focus shifts from the world to the source of understanding itself. The guru’s grace is introduced not as emotional comfort, but as the transmission of insight — a knowledge that does not age, erode, or submit to time. Unlike wealth, the body, power, or relationships, wisdom does not depend on conditions. It remains when everything else falls away.

This distinction is crucial. The bhajan does not propose liberation as an escape from life, but as freedom from confusion. Where the world dissolves, clarity remains. Where forms disappear, understanding endures. Liberation is not something acquired; it is something recognized when illusion drops away.

In this quiet conclusion, the bhajan offers its final teaching without ornament or urgency. What is temporary must be seen clearly, without denial or attachment. What is eternal cannot be held outwardly — it must be realized inwardly. And once that realization occurs, nothing else needs to be said.

The Core Philosophy of the Bhajan

- Everything material is temporary

- Ego is rooted in illusion

- Suffering comes from attachment to permanence

- Freedom comes from understanding impermanence

- Liberation is timeless, not fragile

Why This Bhajan Matters Today

Modern life magnifies ego through status, productivity, and visibility. Social media rewards permanence we do not possess. This bhajan cuts through that noise with ancient clarity.

It does not ask us to renounce life — only to see it truthfully.

To live like a drop of dew is not to disappear.

It is to live lightly, without fear, without false pride.

Conclusion: Living Without Illusion

Mat Kar Maaya Ko Ahankar is not a rejection of the world. It is a rejection of deception. It teaches us to participate fully — while knowing that nothing we touch is permanent.

And in that knowing, something remarkable happens:

fear loosens its grip,

ego softens,

and freedom begins.

This is a traditional Indian devotional bhajan.

The English translation and commentary are original and written for ThePoemStory.

Continue Reading Poetry

Some poems stay with us longer than others. If these words lingered, there are many more waiting—quiet, thoughtful, and written for moments just like this.