The Birth of Hinduism is not marked by a single date, a founding prophet, or one defining revelation. Instead, it is the story of a civilization slowly discovering meaning — through rituals, philosophy, nature, and lived experience. Hinduism did not appear suddenly in India; it took shape over thousands of years, shaped by changing societies, evolving ideas, and continuous questioning about life, duty, and the universe.

To ask about the Birth of Hinduism is not to look for an origin point in time, but to trace a long process of transformation. From early ritual practices of ancient settlements to the philosophical depth of the Vedas and Upanishads, and later to devotional traditions and temples, Hinduism emerged gradually — absorbing, adapting, and redefining itself across generations.

This exploration looks beyond myths and assumptions to understand how Hinduism came into effect in India — not as a fixed system imposed at once, but as a living tradition shaped by history, culture, and human thought.

Explore History and Biographies category.

Table of Contents

Birth of Hinduism: A Question That Has No Single Date

When did Hinduism begin?

This question seems simple, yet it resists a simple answer. Most major religions can be traced to a historical moment — the life of a founder, a revelation, or the writing of a sacred text. Hinduism does not fit into this framework. There is no single individual who can be identified as its originator, no fixed year that marks its beginning, and no singular event that announces its arrival.

The Birth of Hinduism is therefore not an event in history, but a process in civilization.

Why Hinduism Has No Founding Moment

Hinduism developed in a region that supported continuity rather than rupture. The Indian subcontinent, with its rivers, fertile plains, forests, and seasonal rhythms, allowed cultural practices to persist, adapt, and layer upon one another. New ideas did not erase older ones; they were absorbed, reinterpreted, and preserved alongside them.

Because of this, Hinduism grew through:

- inherited rituals passed orally across generations

- evolving social structures and occupations

- philosophical inquiry into life, death, and consciousness

- everyday practices shaped by geography and community

Rather than being defined by a single doctrine, Hinduism became a network of traditions, unified not by uniform belief but by shared cultural memory.

Religion as Lived Experience, Not Sudden Revelation

In its earliest phases, what we now call Hinduism was not recognized as a religion at all. There were no temples, no standardized prayers, and no organized priesthood. Spiritual life was expressed through seasonal rituals, respect for natural forces, and symbolic acts tied to survival and social order.

Over time, these practices gained structure. Rituals became formalized, philosophies emerged to question their meaning, and stories were told to explain the relationship between humans, nature, and the cosmos. Each phase added depth, but none replaced the previous one entirely.

This continuity is why Hinduism appears layered rather than linear.

Stepping Away from Modern Labels

The word Hinduism itself is a modern construction. Applying it retrospectively to ancient practices can create the illusion of a unified system that did not exist in the same way thousands of years ago. Early communities did not identify themselves as “Hindus,” nor did they conceive their practices as belonging to a single religious identity.

Understanding how Hinduism came into effect in India therefore requires stepping away from present-day definitions. It requires viewing history not through fixed categories, but through gradual cultural evolution — where belief systems emerge from daily life, respond to social needs, and mature through reflection and reinterpretation.

A Civilization in Motion

Hinduism did not begin because it did not need to. It grew as Indian society grew. It changed as people questioned ritual, explored philosophy, and sought meaning beyond survival. What we see today as Hinduism is the result of centuries of accumulation — not invention.

The Birth of Hinduism, then, is not a moment to be dated. It is a continuum to be understood.

Before Hinduism: Spiritual Life in Ancient India

Long before the word Hindu existed — and long before religious identity became formalized — the Indian subcontinent already displayed signs of complex spiritual life. These early expressions were not shaped by doctrine or scripture, but by environment, survival, and symbolic meaning.

The earliest clear archaeological window into this world comes from the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 2600–1900 BCE), one of the world’s oldest urban cultures.

The Indus Valley Civilization: Ritual Without Religion

Excavations at sites such as Harappa and Mohenjo-daro reveal a society that was highly organized, technologically advanced, and symbolically expressive. While no religious texts survive from this civilization, material evidence points to structured ritual behavior.

Archaeological findings suggest:

- Ritual bathing, most notably the Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro, indicating purification practices that carried symbolic or communal significance

- Seals and iconography depicting animals, trees, and human-like figures in seated or meditative postures

- Reverence for fertility and nature, reflected in recurring motifs linked to animals, plants, and possibly mother-goddess symbolism

These elements suggest that spiritual meaning was embedded in daily life rather than separated into a religious institution.

What Is Absent Matters Just as Much

Equally important is what the Indus Valley does not show:

- no temples or monumental religious structures

- no evidence of a priestly class or centralized religious authority

- no known scriptures, hymns, or theological systems

This absence is significant. It indicates that while ritual and symbolism existed, organized religion had not yet taken form. There was no codified belief system, no hierarchy controlling spiritual life, and no formal separation between the sacred and the social.

Ritualistic Spirituality, Not Organized Religion

The spiritual life of the Indus Valley appears to have been ritualistic rather than doctrinal. Practices were likely tied to seasonal cycles, fertility, water, and protection — concerns rooted in survival and community cohesion.

Rather than worshipping defined gods with fixed identities, people likely engaged with symbols and forces they believed influenced nature and human life. Meaning was expressed through action and symbol, not belief statements or theology.

Before Religion Took Shape

This stage of Indian spiritual history represents a world before religion crystallized into structured systems. There was spirituality, but not religion as we recognize it today. No clear boundaries existed between ritual, culture, and daily existence.

These early practices did not disappear. Instead, they formed a cultural substratum — influencing later developments when rituals became formalized, philosophies emerged, and belief systems took shape.

Understanding this phase helps explain why Hinduism would later emerge not as a sudden invention, but as a continuation and transformation of older ways of understanding the world.

The Vedic Phase: The Structural Foundation (c. 1500–1000 BCE)

The next major transformation in India’s spiritual history came with the Vedic period. This phase did not mark the birth of Hinduism, but it laid the structural and conceptual foundation upon which Hinduism would later develop.

For the first time, spiritual practices began to take a more defined and transmissible form — not through institutions or temples, but through ritual, language, and memory.

Composition of the Vedas

The earliest identifiable layer of Hindu thought appears in the Vedas, a collection of hymns and ritual texts composed and preserved orally over many centuries. Among them, the Rigveda stands as the oldest surviving record of early Indian religious thought.

These texts were not philosophical treatises or moral codes. They were practical, ritual-oriented compositions meant to be recited, not read. Knowledge was preserved through precise oral transmission, where sound, rhythm, and memorization were considered sacred in themselves.

Core Features of Vedic Religion

The Vedic worldview revolved around maintaining harmony between humans and the cosmos. This relationship was managed through ritual action rather than personal belief.

Key characteristics included:

- Hymns addressed to natural forces, such as Agni (fire), Indra (storm and strength), and Varuna (cosmic order)

- Oral transmission, with no reliance on written doctrine or scripture

- Yajnas (sacrificial rituals) performed by trained priests to sustain cosmic balance

These rituals were not symbolic alone; they were believed to actively maintain the order of the universe.

Cosmic Order Over Personal Faith

At this stage, belief centered on the concept of ṛta — the cosmic order that governed nature, seasons, and moral balance. Human responsibility lay in supporting this order through correct ritual performance.

Importantly:

- gods were impersonal forces, not personal saviors

- devotion was secondary to precision

- ritual correctness mattered more than inner faith

There was little concern for salvation, liberation, or personal spirituality. The focus was external, communal, and cosmic.

A Religion of Action, Not Identity

Vedic religion was not about religious identity in the modern sense. There was no concept of conversion, no exclusive belief system, and no singular path to truth. Participation was defined by role and ritual, not personal conviction.

This makes it fundamentally different from Hinduism as practiced today.

Not Yet Hinduism

While later Hindu traditions would inherit many ideas from the Vedic world — including sacred sound, ritual, and philosophical inquiry — the Vedic system itself was not Hinduism. It lacked:

- temples

- devotional worship

- personal gods

- philosophical liberation doctrines

Instead, it represents an early religious framework, one concerned with sustaining the universe rather than transforming the self.

This Vedic phase provided structure, language, and ritual logic — elements that would later be questioned, reinterpreted, and expanded as Indian spirituality moved from ritual toward philosophy and devotion.

From Ritual to Philosophy: The Upanishadic Shift (c. 800–500 BCE)

Over time, the ritual-heavy Vedic system began to face quiet but profound questioning. As sacrifices grew increasingly elaborate and priest-centered, some thinkers began to ask whether ritual alone could truly explain existence, suffering, and consciousness.

This questioning marked a decisive shift — from external action to internal inquiry.

The Emergence of the Upanishads

This new way of thinking found expression in the Upanishads, composed as reflections, dialogues, and teachings passed from teacher to student. Unlike the Vedas, the Upanishads were not concerned with maintaining cosmic order through sacrifice. They were concerned with understanding reality itself.

The Upanishads did not reject the Vedas outright, but they reinterpreted them. Ritual was no longer dismissed, but it was no longer sufficient.

Radical Questions That Changed Indian Thought

The Upanishadic thinkers asked questions that had never been central before:

- What is the self (Ātman)?

Is it the body, the mind, or something beyond both? - What is ultimate reality (Brahman)?

Is there a single underlying principle behind the diversity of the world? - Is ritual enough, or is knowledge superior?

Can liberation be achieved through action alone, or does it require insight?

These were not abstract philosophical exercises. They were existential questions rooted in human experience — birth, suffering, death, and the search for meaning.

A Shift Away from Sacrifice

During this phase:

- dependence on large-scale sacrificial rituals declined

- authority shifted from priests to teachers and sages

- forests and hermitages became centers of learning, not altars

Spiritual progress was no longer measured by ritual precision, but by understanding and realization.

The Birth of Core Concepts

Some of the most enduring ideas of Hindu philosophy emerged during this period:

- Karma — the principle that actions have consequences beyond a single lifetime

- Rebirth (saṃsāra) — the cycle of birth, death, and return

- Moksha — liberation from this cycle through knowledge

Crucially, liberation was no longer something granted by gods through ritual. It was something realized through insight.

Spirituality Turns Inward

With the Upanishads, Indian spirituality underwent an inward turn. Truth was no longer sought only in fire altars and hymns, but within consciousness itself. The ultimate discovery was not a distant god, but the realization that Ātman and Brahman are one.

This idea transformed the spiritual landscape permanently.

Laying the Philosophical Backbone of Hinduism

The Upanishadic shift did not create Hinduism overnight. But it provided Hinduism with:

- metaphysical depth

- philosophical flexibility

- room for multiple paths to truth

Later devotional movements, ethical systems, and theological schools would all build upon this foundation.

If the Vedic period gave Indian religion its structure, the Upanishads gave it soul and intellect.

The Epic and Puranic Synthesis (c. 300 BCE – 500 CE)

By the early centuries of the Common Era, Indian spirituality entered a phase of integration and accessibility. Philosophical ideas that had once been confined to sages and students were now translated into stories, symbols, and devotional practices that ordinary people could relate to.

This period marks a crucial synthesis — where ritual, philosophy, mythology, and ethics came together. It is during this time that recognizable Hinduism begins to take shape.

A Shift Toward Personal Deities

One of the most significant developments of this era was the rise of personal forms of the divine. The abstract cosmic forces of the Vedic age and the philosophical absolutes of the Upanishads were now expressed through relatable divine personalities.

Major devotional traditions emerged around deities such as:

- Vishnu, associated with preservation and moral order

- Shiva, representing transformation and ascetic insight

- Devi, embodying power, protection, and compassion

These gods were no longer distant cosmic forces. They could be loved, feared, prayed to, and personally connected with.

The Power of Epic Storytelling

Philosophical ideas now found expression through epic narratives, most notably the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.

These epics:

- presented moral dilemmas through human characters

- explored duty (dharma), loyalty, sacrifice, and justice

- blended divine intervention with human struggle

Rather than abstract concepts, people encountered ethics and philosophy through stories, making religious thought emotionally resonant and socially relevant.

The Role of the Puranas

Alongside the epics, the Puranas played a key role in shaping popular Hinduism. The Puranas organized complex ideas into rich narratives that connected:

- gods and their genealogies

- cosmic creation and destruction

- moral consequences of human actions

Through these stories, philosophy was woven into mythology, and belief became inseparable from culture.

Religion Becomes Accessible and Emotional

During this phase, religion underwent a fundamental transformation. It became:

- accessible — no longer limited to priests or philosophers

- emotional — centered on devotion, love, fear, and surrender

- narrative-driven — taught through stories rather than rituals alone

Spiritual practice was no longer confined to sacrifice or meditation. It entered homes, festivals, songs, and daily life.

Temples, Pilgrimages, and Devotion

This period also saw the rise of:

- permanent temples as centers of worship

- pilgrimages connecting geography with sacred memory

- devotional practices (bhakti) focused on personal connection

Religion became visible in architecture, art, and community life — embedding itself deeply into society.

The Formation of Recognizable Hinduism

By the end of this period, most of the elements associated with Hinduism today were firmly in place:

- multiple paths to the divine

- personal gods alongside philosophical depth

- ritual, devotion, and storytelling coexisting

Hinduism was no longer only a system of ritual or philosophy. It had become a living, shared tradition, practiced across regions and generations.

This synthesis did not erase earlier traditions — it absorbed them. And in doing so, it gave Hinduism its enduring, pluralistic character.

The Word “Hindu”: A Cultural Identity, Not a Religious Birth

One of the most important — and often misunderstood — aspects of Hinduism is the origin of the word Hindu itself. Contrary to popular belief, the term did not arise from within Indian religious or philosophical traditions. It was not used in the Vedas, the Upanishads, the epics, or the Puranas.

The word Hindu began as a geographical and cultural label, not a religious one.

A Name Rooted in Geography

The term derives from the river Sindhu River. In ancient Sanskrit texts, Sindhu referred both to the river and, more broadly, to the land around it.

When Persian speakers encountered this region, linguistic shifts transformed Sindhu into Hindu. For them, the term simply meant the people living beyond the Indus River.

At this stage:

- it carried no religious meaning

- it did not refer to belief or practice

- it was a marker of location and culture

A Label Used by Outsiders

For centuries, Hindu remained an external designation. Persians, Greeks, and later other foreign observers used the word to describe the inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent, regardless of their specific customs or beliefs.

A person was called Hindu not because of what they worshipped, but because of where they lived.

This is crucial to understanding why Hinduism does not resemble religions founded around a single doctrine or identity. The label came after the traditions were already in place.

From Cultural Term to Religious Identity

Only much later — particularly during the medieval and early modern periods — did Hindu begin to take on a religious meaning. As interactions with other organized religions increased, there arose a need to describe and group the diverse traditions of India under a single umbrella.

Gradually, Hindu came to signify:

- a religious identifier

- a collective name for many philosophies, rituals, and devotional paths

- a way to distinguish indigenous traditions from others

Importantly, this did not unify beliefs — it unified identity.

Naming What Already Existed

By the time the word Hinduism gained currency, the practices it described were already ancient. Ritual traditions, philosophical schools, devotional movements, and social customs had developed independently over centuries.

Hinduism was not created by naming it.

It was named because it already existed.

Why This Distinction Matters

Understanding the origin of the word Hindu helps explain why Hinduism:

- has no single founder

- accommodates multiple, even contradictory philosophies

- allows ritual, devotion, and philosophy to coexist

It also clarifies why Hinduism functions less like a centralized religion and more like a civilizational framework — one that grew organically and was later identified as a whole.

The word came late.

The tradition came first.

So, When Did Hinduism Begin?

The honest answer is both simple and profound.

Hinduism did not begin.

It became.

Unlike religions that trace their origins to a founding figure or a defining moment, Hinduism emerged through a long and continuous process of cultural and spiritual evolution. It was shaped not by revelation at a single point in time, but by centuries of human experience, questioning, adaptation, and synthesis.

A Tradition Formed Over Millennia

Hinduism took form gradually through multiple phases:

- Prehistoric ritual practices, rooted in nature, survival, and symbolism

- Vedic sacrificial systems, which introduced structure, sacred language, and cosmic order

- Philosophical inquiry, where thinkers questioned ritual and turned inward in search of truth

- Devotional movements, which made spirituality personal, emotional, and accessible

- Social and cultural synthesis, where stories, temples, ethics, and daily practices merged into lived tradition

Each phase added depth without erasing what came before. Instead of replacement, there was accumulation.

Not Founded, But Formed

To search for a founding date of Hinduism is to apply a modern framework to an ancient reality. Hinduism did not arise as a system to be adopted or imposed. It emerged as a way of understanding life — shaped by geography, society, and sustained reflection.

It absorbed contradictions.

It allowed multiple paths.

It survived because it adapted.

A Living, Evolving Tradition

Hinduism is best understood not as a religion founded in time, but as a living tradition shaped by history. Its continuity lies not in uniform belief, but in its capacity to evolve while retaining memory.

This is why Hinduism contains:

- ritual and philosophy

- devotion and skepticism

- discipline and spontaneity

It is not frozen in its origins.

It moves with time.

The Meaning of Becoming

To say Hinduism became is not to deny its depth — it is to recognize its resilience. What emerged over millennia was not a single doctrine, but a civilizational response to existence itself.

And that is why Hinduism has endured — not because it began once, but because it continues to become.

Why This Understanding Matters Today

Understanding the birth of Hinduism is not merely an academic exercise. It shapes how religion is perceived, practiced, and discussed in the modern world. When Hinduism is viewed through its historical evolution rather than as a fixed system, several important insights emerge.

Religion Is Not Static

Hinduism reminds us that religious traditions are not frozen at the moment of their earliest expression. They grow, absorb influences, reinterpret ideas, and respond to changing realities. What existed as ritual in one era transformed into philosophy in another, and later into devotion and social practice.

Change, in this context, is not corruption.

It is continuity.

Belief Systems Respond to Society

As societies evolve, so do their spiritual needs. The questions asked by people living in forests, cities, kingdoms, or modern nation-states are not the same. Hinduism’s ability to adapt — from sacrificial rituals to introspective philosophy, from abstract metaphysics to personal devotion — reflects this responsiveness.

This adaptability is not accidental. It is one of the reasons Hinduism has remained relevant across centuries of social, political, and cultural change.

Diversity Is Natural, Not Contradictory

One of the most misunderstood aspects of Hinduism is its internal diversity. Multiple philosophies, rituals, and devotional paths often coexist, sometimes appearing contradictory from the outside. Historical understanding reveals that this diversity is not a flaw — it is the outcome of layered development.

Different paths emerged to meet different human needs.

All were allowed to exist.

Unity in Hinduism does not come from uniform belief, but from shared cultural and philosophical space.

Faith and History Are Not Opposites

A historical understanding of Hinduism does not weaken faith. It deepens it. Knowing how traditions formed, adapted, and survived adds context, humility, and respect. Faith becomes informed rather than fragile.

When belief is grounded in understanding, it becomes more resilient — not less.

A Tradition That Endures by Evolving

Hinduism has endured not because it resisted change, but because it accommodated it. Its strength lies in its capacity to evolve while retaining memory, meaning, and continuity.

Understanding this evolution allows modern readers to engage with Hinduism not as a rigid inheritance, but as a living tradition — one that invites reflection, adaptation, and respect.

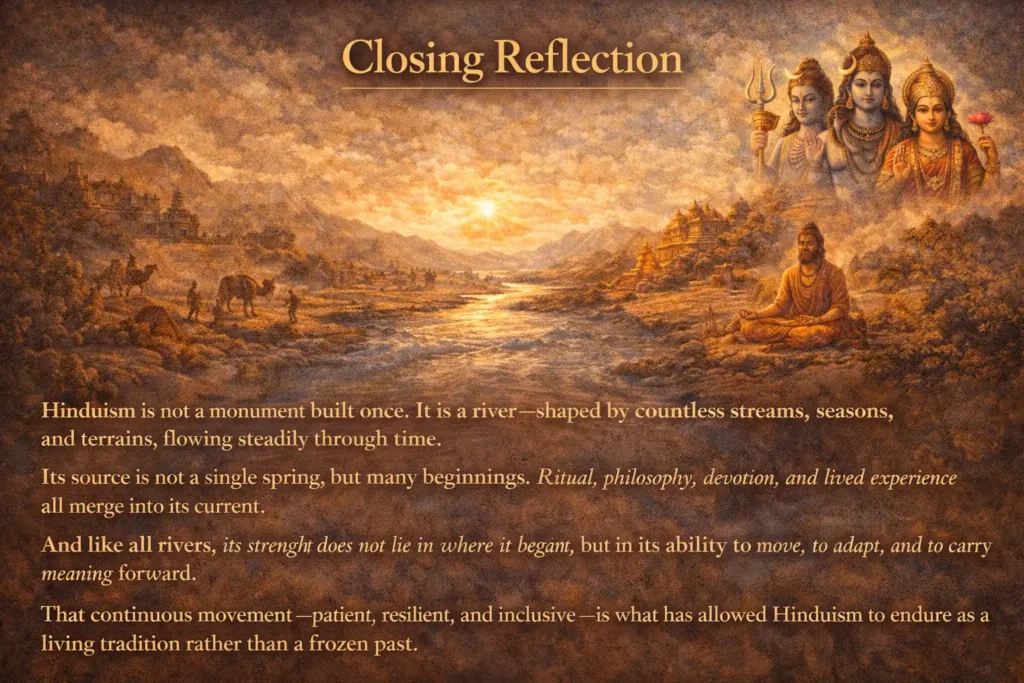

Closing Reflection

Hinduism is not a monument built once.

It is a river — shaped by countless streams, seasons, and terrains, flowing steadily through time.

Its source is not a single spring, but many beginnings.

Ritual, philosophy, devotion, and lived experience all merge into its current.

And like all rivers, its strength does not lie in where it began,

but in its ability to move, to adapt, and to carry meaning forward.

That continuous movement — patient, resilient, and inclusive — is what has allowed Hinduism to endure as a living tradition rather than a frozen past.

Hinduism did not begin at a single moment in history. It evolved — shaped by ritual, philosophy, and devotion — flowing through time as a living tradition.

How Hinduism Came Into Effect in India (FAQ)

When did Hinduism begin?

Hinduism did not begin on a single date or with a single founder. It evolved gradually over thousands of years, starting from early ritual practices in ancient India and developing through philosophical, devotional, and social traditions.

Is Hinduism older than other major religions?

Yes. Hinduism is widely considered one of the world’s oldest continuously practiced religious traditions, with roots stretching back to the early Vedic period and even earlier cultural practices.

Did Hinduism originate from the Vedas?

The Vedas played a foundational role, but Hinduism did not suddenly begin with them. The religion evolved through multiple phases—ritualistic, philosophical, and devotional—absorbing ideas over time.

Was Hinduism always a structured religion?

No. Early Hindu traditions were not centralized or institutionalized. Temples, priestly systems, and formal doctrines developed much later as society became more complex.

Is Hinduism a single religion or a collection of traditions?

Hinduism is best understood as a broad family of spiritual traditions rather than a single, uniform religion. It includes diverse beliefs, practices, philosophies, and devotional paths.

How did philosophy enter Hinduism?

Philosophical inquiry emerged prominently during the Upanishadic period, where thinkers began questioning ritualism and explored deeper ideas such as the self, reality, and liberation.

Did Hinduism change over time?

Yes. Change is a defining feature of Hinduism’s continuity. Ritual practices evolved into philosophical systems, which later expanded into devotional movements and social traditions.

Is Hinduism tied to one god or belief system?

No. Hinduism accommodates monotheism, polytheism, monism, atheistic philosophies, and devotional practices, allowing individuals to follow paths aligned with their understanding.

Was Hinduism influenced by historical events?

Yes. Social changes, migrations, political structures, and cultural interactions all influenced how Hindu practices and beliefs developed across different eras.

Why is understanding the birth of Hinduism important today?

Understanding Hinduism’s historical evolution helps dispel myths, reduce polarization, and promote a more informed and respectful discussion about religion in the modern world.

Does studying Hinduism historically weaken faith?

No. Viewing Hinduism through its historical development enriches understanding. Change in tradition represents continuity, not corruption.

Is Hinduism still evolving today?

Yes. Like all living traditions, Hinduism continues to adapt to social, cultural, and philosophical changes while retaining its core spiritual ideas.

Continue Reading History

History often reveals itself slowly—through patterns, pauses, and questions that refuse simple answers. If this exploration stayed with you, there are more essays waiting, tracing civilizations, ideas, and the human stories behind them.