In this post “10 Architectural Marvels of Hindu India: A Historian’s Journey Through Stone and Spirit“. Explore the magnificent Hindu architectural marvels of India through the eyes of a 20-year historian. Discover the intricate artistry, engineering brilliance, and spiritual significance of India’s greatest temples – from Khajuraho’s sublime sculptures to Brihadeeswarar’s towering grandeur. An in-depth journey through 10 extraordinary monuments that showcase the evolution of Hindu temple architecture across centuries.

Also Read:

- The Hoysala Empire: A Comprehensive Historical Analysis

- Rajaraja Chola and Rajendra Chola: Empire Builders, Ocean Conquerors, and Timeless Lessons in Leadership

Table10 Architectural Marvels of Hindu India

Introduction – Architectural Marvels of Hindu India

As a historian who has spent two decades traversing the sacred landscapes of India, studying the evolution of Hindu temple architecture, I have witnessed firsthand the breathtaking magnificence of monuments that stand as eternal testimonies to human devotion and artistic genius. These architectural marvels are not merely structures of stone and mortar – they are profound expressions of faith, repositories of ancient wisdom, and masterpieces of engineering that continue to inspire awe more than a millennium after their creation.

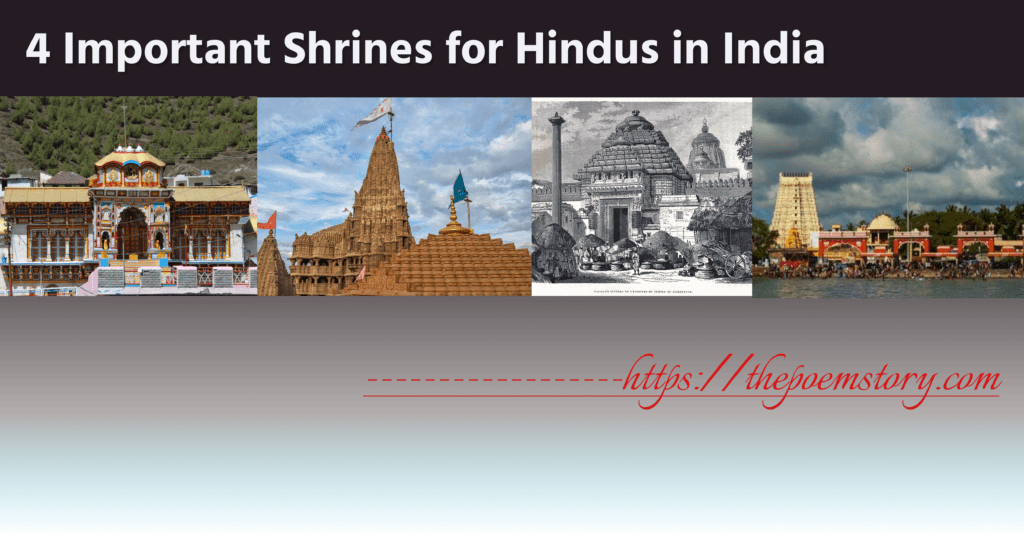

Hindu temple architecture represents one of humanity’s most sophisticated architectural traditions, evolving across regional styles and dynastic periods. The three principal styles – Nagara in the north, Dravidian in the south, and Vesara in the Deccan – each developed unique characteristics that reflect local cultural influences and spiritual philosophies. From the curvilinear towers of northern India to the pyramidal vimanas of the south, these monuments showcase an extraordinary diversity of artistic expression while maintaining underlying principles of sacred geometry and cosmic symbolism.

The creative genius of ancient Indian architects manifested in their ability to transform religious and philosophical concepts into tangible forms. Every element – from the orientation toward the rising sun to the intricate iconographic programs carved into walls – served both functional and spiritual purposes. These temples embody the Hindu concept of the cosmos in miniature, with sanctums representing Mount Meru and surrounding structures symbolizing the layers of creation.

1. Khajuraho Group of Monuments – The Sublime Symphony of Stone (Architectural Marvels of Hindu India)

Stone carvings on Khajuraho temple walls showing intricate Hindu architectural sculpture from India’s medieval period

Standing before the temples of Khajuraho on a misty dawn, I am transported to an era when the Chandela dynasty ruled central India with unprecedented artistic vision. Built between 950 and 1050 CE, these monuments represent the pinnacle of Nagara-style temple architecture, where sensuality and spirituality converge in perfect harmony.

The genius of Khajuraho lies not merely in its architectural grandeur but in its revolutionary approach to temple ornamentation. Walking through the western cluster, I am struck by the temple builders’ unprecedented boldness in depicting the full spectrum of human experience. The Kandariya Mahadeva Temple, standing 116 feet tall with over 870 sculptures, exemplifies this artistic courage. Each carving tells a story – from celestial apsaras dancing in eternal bliss to intricate depictions of daily life, warfare, and yes, the celebrated erotic sculptures that represent the tantric philosophy of transcending physical desires to achieve spiritual liberation.

The architectural sophistication becomes evident when examining the temple’s structural elements. The elevated jagati platforms, the gradual recession of walls creating the distinctive pancharatha plan, and the soaring shikharas crowned with amalaka and kalasha demonstrate the mathematical precision underlying Hindu temple construction. The temples face east to capture the first rays of sunrise, embodying the Hindu principle of moving from darkness to light, ignorance to knowledge.

What strikes me most profoundly during my repeated visits is the acoustic engineering embedded within these structures. The pillared halls were designed to amplify chants and prayers, creating an immersive spiritual experience that engaged all the senses. The integration of sculpture, architecture, and sacred acoustics represents a holistic approach to temple design that modern architects still study and admire.

The survival of only 20 temples from the original 85 speaks to both the ravages of time and the resilience of artistic legacy. Each surviving structure is a precious manuscript written in stone, preserving not just architectural techniques but entire philosophical systems and cultural practices of medieval India.

Summary:

- Built by Chandela dynasty between 950-1050 CE

- Exemplifies Nagara-style temple architecture with pancharatha plan

- Features over 870 sculptures in Kandariya Mahadeva Temple

- Showcases integration of sensual and spiritual themes

- Demonstrates advanced acoustic and structural engineering

- Only 20 temples survive from original 85 structures

2. Brihadeeswarar Temple, Thanjavur – The Colossus of Chola Magnificence (Architectural Marvels of Hindu India)

The moment I first glimpsed the towering vimana of Brihadeeswarar Temple rising 216 feet into the Tamil sky, I understood why it has been called Dakshina Meru – the Mount Meru of the South. Built by the great Chola emperor Rajaraja I between 1003-1010 CE, this architectural colossus represents the zenith of Dravidian temple architecture and stands as the largest temple in India.

The engineering marvel begins with the very foundation. The entire structure was constructed using granite blocks transported from quarries over 60 kilometers away, assembled without a single drop of mortar. The precision with which these massive stones fit together demonstrates the mathematical and engineering acumen of Chola architects. The 80-ton capstone crowning the vimana was raised using an ingenious ramp system that extended over 6 kilometers – a feat of ancient engineering that rivals modern construction techniques.

Walking through the temple complex, I am continually amazed by the sophisticated understanding of proportion and scale. The vimana rises in distinct tiers, each level precisely calculated to create visual harmony from ground level. The sanctum houses a massive 13-foot lingam carved from a single stone, while the surrounding walls showcase exquisite Chola bronze sculptures and vibrant frescoes depicting scenes from Hindu epics.

The temple’s iconographic program reveals the political and religious aspirations of Rajaraja I. Inscriptions record the emperor’s military victories, administrative systems, and the elaborate devadasi tradition that supported temple activities. The walls themselves serve as historical documents, preserving detailed records of land grants, taxation systems, and the socio-economic life of the Chola period.

What makes this temple architecturally revolutionary is its synthesis of monumental scale with intricate detail. Every surface – from the massive exterior walls to the intimate sanctum chambers – is adorned with sculptures that demonstrate the Chola mastery of metallurgy, stone carving, and architectural ornamentation. The temple established architectural principles that influenced South Indian temple construction for centuries.

The Nandi pavilion housing the massive bull sculpture, the surrounding prakara walls with their defensive bastions, and the systematic arrangement of subsidiary shrines create a perfect mandala in stone. This cosmic symbolism, combined with the temple’s astronomical alignments, reflects the Hindu understanding of architecture as a bridge between earthly and celestial realms.

Summary:

- Built by Chola Emperor Rajaraja I (1003-1010 CE)

- Stands 216 feet tall as India’s largest temple

- Constructed entirely with granite without mortar

- Features 80-ton capstone raised via 6km ramp system

- Houses 13-foot monolithic lingam in sanctum

- Contains detailed inscriptions documenting Chola administration

3. Konark Sun Temple – The Cosmic Chariot of Surya (Architectural Marvels of Hindu India)

Approaching Konark at dawn, as the first rays of sunlight illuminate the stone chariot emerging from coastal mists, I experience what medieval pilgrims must have felt witnessing this 13th-century masterpiece dedicated to Surya, the Sun God. Designed by the legendary architect Bishu Maharana during the reign of Narasimhadeva I (1250-1260 CE), this temple represents the pinnacle of Kalinga architecture and stands as one of the world’s most ambitious architectural undertakings.

The genius of Konark lies in its perfect synthesis of architecture, astronomy, and mythology. The entire temple is conceived as Surya’s celestial chariot, complete with 24 elaborately carved wheels, each nearly 12 feet in diameter, drawn by seven stone horses representing the days of the week. The wheels themselves are masterpieces of mathematical precision, functioning as sundials that accurately indicate time throughout the day – a testament to the architect’s understanding of solar movements and geometric principles.

The temple’s orientation demonstrates sophisticated astronomical knowledge. The main entrance faces east to capture the first rays of sunrise, while the sanctum was positioned to allow sunlight to illuminate the presiding deity during equinoxes. This integration of architecture with celestial mechanics reflects the Hindu belief in the correspondence between cosmic order and earthly structures.

The sculptural program at Konark is overwhelming in its scope and sophistication. The basement level features 1,452 elephants in various poses, symbolizing stability and strength, while the upper levels display an encyclopedia of medieval Indian life. From royal processions and battle scenes to musicians and dancers, the temple walls preserve a comprehensive record of 13th-century Odishan society. The controversial erotic sculptures, like those at Khajuraho, represent tantric philosophy and the integration of worldly and spiritual experiences.

The structural engineering demonstrates remarkable innovation. The laterite core was covered with sandstone blocks held together by iron clamps, creating a stable foundation for the massive superstructure. The use of magnetism in the temple’s construction – with a 52-ton magnetic capstone – showcases the builders’ understanding of natural forces and their architectural applications.

What makes Konark truly extraordinary is its current state of preservation. Though the main shikhara has collapsed, enough remains to appreciate the original conception. The surviving Jagamohana (assembly hall) displays the complete Kalinga architectural vocabulary: the horseshoe arch motifs, tiered roofing, and intricate surface ornamentation that influenced temple construction across eastern India.

Summary:

- Built by architect Bishu Maharana (1250-1260 CE)

- Designed as Surya’s chariot with 24 carved wheels and 7 horses

- Wheels function as precise sundials indicating time

- Features 1,452 elephant sculptures at basement level

- Utilizes magnetic capstone weighing 52 tons

- Demonstrates advanced understanding of astronomy and geometry

4. Angkor Wat, Cambodia – The Hindu Temple That Conquered Time (Architectural Marvels of Hindu India)

Standing within the 208-hectare complex of Angkor Wat, surrounded by its 5.5-kilometer moat, I am reminded that Hindu architectural influence extended far beyond India’s borders, creating monuments that rival anything on the subcontinent. Built by King Suryavarman VII in the early 12th century as a Hindu temple dedicated to Vishnu, Angkor Wat represents the culmination of Khmer architecture and the largest religious monument ever constructed.

The architectural conception of Angkor Wat embodies Hindu cosmology with unprecedented grandeur. The five lotus-bud towers arranged in a quincunx pattern represent the five peaks of Mount Meru, the cosmic mountain at the universe’s center. The surrounding galleries symbolize mountain ranges, while the great moat represents the cosmic ocean – creating a perfect mandala in stone that spans over 500 acres.

What strikes me most about Angkor Wat’s architecture is its sophisticated understanding of perspective and proportion. The temple was designed to be viewed as a unified composition from multiple vantage points, with the central 213-foot tower serving as the focal point visible from great distances. The graduated levels – from the outer causeway through three rectangular galleries to the central shrine – create a processional experience that guides visitors from the earthly realm toward the divine.

The structural engineering demonstrates remarkable sophistication. The entire complex was constructed using sandstone blocks quarried from Mount Kulen, 32 kilometers away, and transported via an elaborate canal system visible in satellite imagery. The precision of stone cutting and assembly, achieved without mortar, rivals the finest Indian temple construction and demonstrates the universal principles underlying Hindu architectural traditions.

The sculptural program reveals the depth of Hindu cultural influence in Southeast Asia. The famous bas-relief galleries stretching over 1,200 meters depict scenes from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Puranas, executed with artistic sophistication that equals contemporary Indian temple sculpture. The integration of Khmer artistic sensibilities with classical Hindu iconography created a unique synthesis that influenced temple construction throughout the region.

The temple’s astronomical alignments demonstrate the universal nature of Hindu architectural principles. The main tower aligns with the spring equinox sunrise, while various architectural elements mark significant solar and lunar events. This integration of architecture with celestial mechanics reflects the shared Hindu understanding of temples as cosmic instruments that connect earthly and heavenly realms.

Angkor Wat’s transformation from Hindu to Buddhist temple, while preserving its original architectural integrity, demonstrates the adaptability of Hindu architectural forms to different religious contexts. The temple continues to function as a living monument, serving contemporary spiritual needs while preserving ancient architectural wisdom.

Summary:

- Built by King Suryavarman VII in early 12th century for Vishnu

- Covers 208 hectares as world’s largest religious monument

- Features five towers representing Mount Meru’s peaks

- Includes 1,200 meters of bas-relief galleries with Hindu epics

- Demonstrates sophisticated astronomical alignments

- Shows Hindu architectural influence in Southeast Asia

5. Kailasa Temple, Ellora – The Monolithic Marvel (Architectural Marvels of Hindu India)

Kailasa Temple at Ellora caves, a stunning monolithic rock-cut Hindu temple adorned with intricate carvings and sculptures

Descending into the vast excavated court surrounding the Kailasa Temple at Ellora, I am confronted with what may be the most audacious architectural undertaking in human history. This 8th-century masterpiece, attributed to Rashtrakuta king Krishna I, was carved entirely from a single cliff face, requiring the removal of 2 million tons of rock to create the world’s largest monolithic temple.

The revolutionary architectural approach at Kailasa overturned conventional temple construction. Instead of building upward with assembled stones, the architects conceived a freestanding temple within the living rock, working from top to bottom to carve out not just interior spaces but complete exterior elevations. This “subtractive architecture” demanded unprecedented planning and visualization skills, as any miscalculation would have been irreversible.

The temple’s design synthesizes architectural influences from across medieval India. The basic plan follows Chalukya prototypes, particularly the Virupaksha Temple at Pattadakal, while the carving techniques demonstrate Pallava influence from Mahabalipuram. The Western Indian cave tradition contributed to the interior spatial concepts, creating a unique architectural vocabulary that transcends regional boundaries.

Walking through the temple complex, I am struck by the architects’ mastery of proportion and scale. The central shrine rises 32 meters from the courtyard floor, crowned by a pyramidal shikhara that perfectly balances mass and verticality. The Nandi pavilion, flanking victory pillars, and surrounding subsidiary shrines create a complex three-dimensional composition that maintains visual coherence despite its enormous scale.

The sculptural program demonstrates the collaborative nature of medieval Indian artistic production. Different sections show distinct regional styles, suggesting master craftsmen from Chalukya, Pallava, and Western Indian traditions working together on this unprecedented project. The famous Ravana lifting Mount Kailasa panel showcases this synthesis, combining monumental scale with intricate detail in a composition that has no parallel in Indian art.

The engineering challenges overcome at Kailasa seem almost impossible by medieval standards. The architects had to maintain structural integrity while removing massive quantities of rock, ensure proper drainage to prevent water damage, and create a stable foundation for the towering superstructure – all while working within the constraints of the existing cliff face. The survival of the temple over twelve centuries testifies to the brilliance of their solutions.

What makes Kailasa truly extraordinary is its theological program. Every sculpture, from the grand narrative panels to the smallest decorative motifs, was conceived to support the political and religious claims of the Rashtrakuta dynasty. The temple functions simultaneously as a cosmic diagram, a dynastic monument, and a devotional space – achieving multiple architectural objectives within a single, unified design.

Summary:

- Carved from single cliff face by Rashtrakuta king Krishna I (8th century)

- Required removal of 2 million tons of rock using top-down technique

- Stands 32 meters high as world’s largest monolithic temple

- Synthesizes Chalukya, Pallava, and Western Indian architectural styles

- Features collaborative sculptural program by regional master craftsmen

- Demonstrates unprecedented engineering and planning capabilities

6. Hoysaleswara Temple, Halebidu – The Jewel of Sculptural Artistry (Architectural Marvels of Hindu India)

Approaching the Hoysaleswara Temple across the manicured lawns of Halebidu, I am immediately struck by the temple’s unique star-shaped platform and the extraordinary density of sculptural ornamentation that covers every available surface. Built in the 12th century during the reign of Vishnuvardhana of the Hoysala dynasty, this temple represents the pinnacle of South Indian sculptural art and demonstrates what Percy Brown called “the supreme climax of Indian architecture”.

The architectural innovation of Hoysala temples lies in their dvikuta vimana plan – essentially two complete temples joined by a common platform. One shrine honors Hoysaleswara (named after the king), while the other is dedicated to Shantaleswara (honoring Queen Shantala Devi). This twin-shrine concept allows for elaborate ceremonial programs while maintaining perfect architectural symmetry.

The temple’s construction material – chloritic schist or soapstone – enabled the extraordinary level of sculptural detail that makes Hoysaleswara unique. This relatively soft stone could be carved with jewel-like precision, allowing artisans to create sculptures that appear almost translucent in places. The result is architectural sculpture that achieves the refinement typically associated with metalwork or ivory carving.

Walking along the temple’s pradakshina path, I am overwhelmed by the sculptural program’s scope and sophistication. The base features eight horizontal bands depicting elephants, lions, horses, floral scrolls, and narrative scenes from Hindu epics. The walls showcase an encyclopedia of Hindu iconography, with over 240 unique wall sculptures depicting deities, sages, and celestial beings. The famous observation by James Fergusson remains valid: “no two canopies in the whole building are alike, and every part exhibits a joyous exuberance of fancy”.

The temple’s lathe-turned pillars represent a remarkable technical achievement. These monolithic columns were shaped with mathematical precision to create perfect cylindrical forms, then carved with intricate surface decoration. The pillars’ mirror-like finish demonstrates the Hoysala sculptors’ mastery of stone polishing techniques that remain unmatched in Indian temple architecture.

The iconographic program reveals the syncretic nature of Hoysala religious culture. While primarily a Shaiva temple, the walls include extensive Vaishnava and Jain imagery, reflecting the dynasty’s religious tolerance and the inclusive nature of medieval South Indian spirituality. The narrative panels depicting scenes from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Bhagavata Purana function as three-dimensional manuscripts, preserving literary traditions in stone.

The temple’s incomplete state – construction was halted during the early 14th century due to Muslim invasions – provides insight into medieval construction techniques. The partially finished sections show how Hoysala artisans worked from detailed sketches to create their masterpieces, with individual sculptors signing their work – a rare practice in Indian temple construction.

Summary:

- Built during 12th century reign of Hoysala king Vishnuvardhana

- Features unique twin-shrine (dvikuta vimana) architectural plan

- Constructed from soapstone enabling extraordinary sculptural detail

- Contains over 240 unique wall sculptures and 8 horizontal frieze bands

- Showcases lathe-turned pillars with mirror-like finish

- Demonstrates religious syncretism with Hindu and Jain imagery

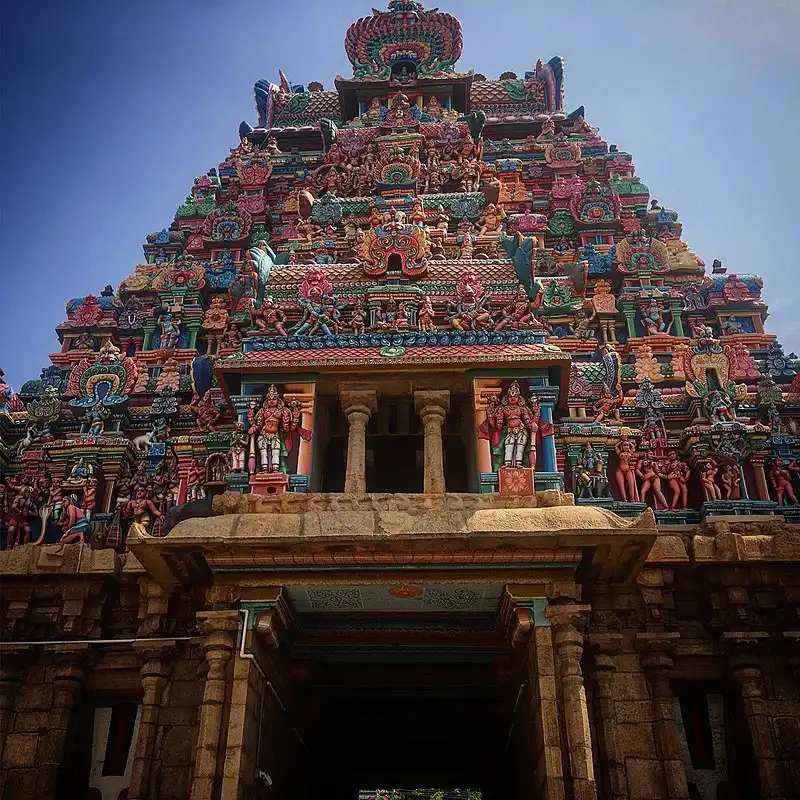

7. Meenakshi Temple, Madurai – The Technicolor Dream of Tamil Architecture (Architectural Marvels of Hindu India)

Standing in the great courtyard of the Meenakshi Amman Temple, surrounded by towering gopurams that seem to pierce the Tamil sky with their riot of colors and forms, I am transported to a realm where architecture transcends mere stone and mortar to become pure visual poetry. This Dravidian masterpiece, rebuilt during the 16th-17th centuries by the Nayak rulers, represents the final flowering of South Indian temple architecture and stands as one of India’s most visually spectacular sacred sites.

The temple’s architectural program is organized around the concept of the divine marriage between Shiva (as Sundareswarar) and Parvati (as Meenakshi), creating a complex cosmic mandala that spreads across 15 acres and incorporates over 30,000 sculptures. The systematic arrangement of concentric enclosures, each marked by progressively taller gopurams, creates a three-dimensional journey from the mundane world toward the divine presence.

What strikes me most powerfully about Meenakshi Temple is its revolutionary approach to color and surface ornamentation. Unlike the monochromatic stone temples of earlier periods, the Nayak architects embraced polychromatic sculpture, creating gopurams that blaze with color like illuminated manuscripts transformed into architecture. The famous Southern Gopuram, rising 170 feet into the sky, displays thousands of painted stucco figures arranged in perfectly ordered hierarchies that tell the entire story of Hindu cosmology.

The architectural sophistication becomes evident when examining the temple’s structural systems. The massive gopurams are constructed using a stone and brick core covered with elaborate stucco ornamentation, allowing for both structural stability and infinite decorative possibilities. The pillared mandapas, including the famous Thousand Pillar Hall (actually containing 985 pillars), demonstrate advanced understanding of load distribution and acoustic design.

The temple’s urban integration represents a revolutionary concept in Indian temple architecture. The Nayak rulers designed the temple complex as the literal and symbolic heart of Madurai city, with streets radiating outward in perfect cardinal alignments. The temple tank, markets, and processional streets create an integrated sacred landscape that encompasses the entire urban environment.

The iconographic program reveals the sophisticated theological concepts underlying Nayak temple architecture. The arrangement of shrines, the positioning of guardian deities, and the distribution of sculptural themes follow principles derived from Agamic texts and Shilpa Shastras, creating a three-dimensional theology textbook. The annual Chithirai festival reenacting the divine marriage transforms the entire temple complex into a stage for cosmic drama.

The temple’s defensive walls and fortified entrances reflect the military realities of 16th-century South India, when temple complexes served as both spiritual centers and political strongholds. The integration of military architecture with sacred design creates a unique architectural synthesis that influenced temple construction throughout the Tamil region.

Summary:

- Rebuilt by Nayak rulers during 16th-17th centuries

- Covers 15 acres with over 30,000 sculptural elements

- Features 14 gopurams with tallest reaching 170 feet

- Incorporates revolutionary polychromatic stucco decoration

- Contains famous Thousand Pillar Hall with 985 columns

- Integrates temple design with entire urban layout of Madurai

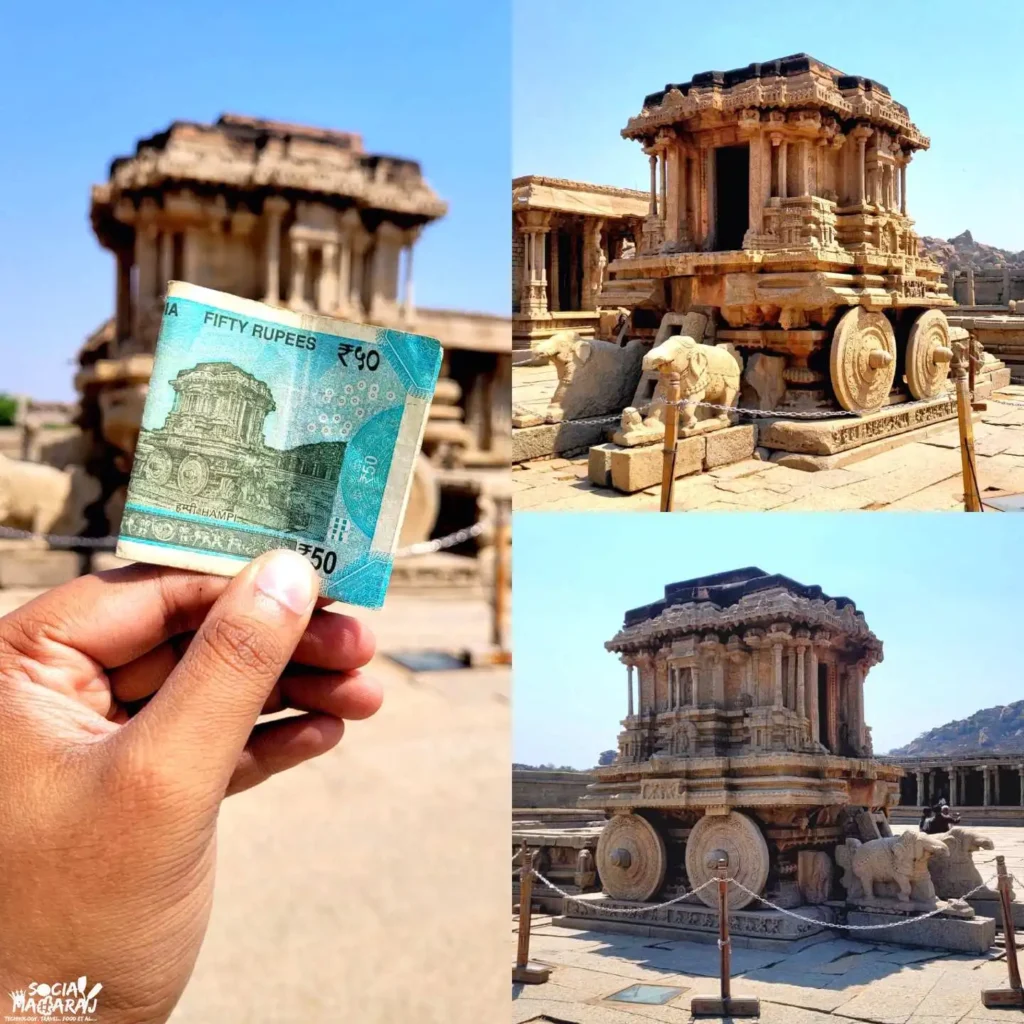

8. Vitthala Temple, Hampi – The Musical Marvel of Vijayanagara (Architectural Marvels of Hindu India)

Walking through the ruins of Hampi toward the Vitthala Temple, I am struck by the dramatic landscape that frames this 16th-century masterpiece – a setting that seems designed by nature itself to showcase the architectural genius of the Vijayanagara Empire. This temple, dedicated to Vitthala (a form of Vishnu), represents the culmination of Vijayanagara architectural style and contains some of the most innovative features in all of Indian temple architecture.

The temple’s fame rests primarily on two extraordinary innovations: the Stone Chariot and the Musical Pillars. The stone chariot, now featured on the Indian 50-rupee note, is a masterpiece of sculptural architecture that appears to be a functional vehicle carved from granite.

Complete with rotating wheels, rearing horses, and intricate surface decoration, this Garuda shrine demonstrates the Vijayanagara sculptors’ ability to transform stone into seemingly organic forms.

The musical pillars represent one of the most remarkable acoustic achievements in world architecture. Each of the 56 pillars in the main mandapa produces distinct musical notes when struck, creating a complete percussion orchestra in stone. The pillars are carved as clusters of smaller columns, with each element tuned to specific pitches through precise mathematical calculations of diameter, length, and internal resonance chambers. This acoustic engineering demonstrates the Vijayanagara architects’ sophisticated understanding of both music theory and structural acoustics.

The temple’s architectural vocabulary synthesizes influences from across South India while creating distinctly Vijayanagara innovations. The characteristic composite pillars feature rearing Yali (mythical lion-elephant creatures) that seem to support the roof structure through pure artistic vitality rather than mere structural necessity. These pillars transform functional architecture into dynamic sculpture, creating interior spaces that pulse with life and movement.

The temple complex demonstrates the Vijayanagara approach to urban planning and ceremonial architecture. The chariot streets flanked by pillared pavilions created processional routes that could accommodate massive festival celebrations. The integration of stepped tanks, subsidiary shrines, and ceremonial platforms creates a complete ritual landscape designed to support the elaborate religious ceremonies that were central to Vijayanagara courtly culture.

The Kalyana Mandapa (marriage hall) and Utsava Mandapa (festival hall) showcase the empire’s distinctive approach to ceremonial architecture. These structures combine Dravidian proportional systems with Islamic architectural elements absorbed through cultural contact, creating a unique synthesis that influenced temple construction throughout South India.

The temple’s current ruined state, paradoxically, enhances its architectural impact. The missing roof structures allow unobstructed views of the extraordinary pillar carving, while the weathered stone surfaces reveal construction techniques and decorative programs that might otherwise be hidden. The temple functions as both architectural masterpiece and archaeological document, preserving evidence of Vijayanagara artistic and technical achievements.

Summary:

- Built during 16th century Vijayanagara Empire peak

- Features iconic Stone Chariot shrine now on Indian currency

- Contains 56 musical pillars producing distinct notes when struck

- Showcases characteristic composite pillars with Yali creatures

- Includes elaborate chariot streets and ceremonial platforms

- Demonstrates synthesis of Dravidian and Islamic architectural elements

9. Jagannath Temple, Puri – The Fortress of Kalinga Faith (Architectural Marvels of Hindu India)

Approaching the Jagannath Temple through the bustling streets of Puri, I am struck by the temple’s fortress-like appearance, its massive walls and towering vimana dominating the coastal landscape like a spiritual citadel. Built by King Anantavarman Chodaganga Deva in the 12th century, this temple represents the pinnacle of Kalinga architecture and stands as one of Hinduism’s most important pilgrimage centers.

The temple’s architectural significance lies in its perfect synthesis of the two primary Kalinga structural systems: Rekha Deula and Pidha Deula. The main vimana (sanctum tower) rises as a curvilinear shikhara in the Rekha style, while the Jagamohana (assembly hall) displays the characteristic pyramidal tiers of the Pidha style. This combination creates a dynamic architectural composition that influenced temple construction throughout eastern India.

The temple’s Pancha Ratha ground plan divides the vimana’s vertical structure into five projected elements on each side, creating a rhythmic interplay of light and shadow that animates the entire structure. The 214-foot tower crowned by the sacred Neelachakra (blue wheel) creates a vertical axis that connects earth and heaven, embodying the Hindu concept of the cosmic pillar.

What makes Jagannath Temple architecturally unique is its complete integration of temple design with ritual function. The four gates – Singhdwara (Lion Gate), Ashwadwara (Horse Gate), Vyaghra Dwara (Tiger Gate), and Hastidwara (Elephant Gate) – each feature sculptural programs that prepare pilgrims psychologically for darshan of the deity. The systematic progression through Bhoga Mandapa, Natamandira, Jagamohana, and finally the sanctum creates a carefully orchestrated spiritual journey.

The temple’s daily flag-changing ceremony atop the vimana represents one of India’s most remarkable architectural-ritual traditions. The precision required to maintain this ancient practice demonstrates the builders’ sophisticated understanding of structural engineering and access systems. The temple’s survival through centuries of coastal storms and political upheavals testifies to the soundness of Kalinga construction techniques.

The architectural iconography of Jagannath Temple reflects the unique theological synthesis that characterizes Odishan Hinduism. The temple houses wooden images of Jagannath, Balabhadra, and Subhadra – a departure from stone sculpture that necessitated special architectural provisions for periodic renewal. The famous Rath Yatra (chariot festival) transforms the temple’s processional streets into sacred geography, extending the temple’s architectural influence throughout the entire city of Puri.

The temple’s fortified walls and defensive bastions reflect the military architecture of medieval Odisha, when major temples served as political and economic centers requiring protection. The integration of sacred and secular architectural elements creates a complex that functions simultaneously as temple, fortress, and urban center – a comprehensive approach to architectural planning that influenced later Odishan temple construction.

Summary:

- Built by King Anantavarman Chodaganga Deva in 12th century

- Exemplifies Kalinga architecture combining Rekha and Pidha styles

- Features 214-foot vimana with sacred Neelachakra crown

- Incorporates Pancha Ratha ground plan with five projected elements

- Houses unique wooden deities requiring periodic renewal

- Functions as integrated temple-fortress-urban complex

10. Shore Temple, Mahabalipuram – The Pallava Pioneer (Architectural Marvels of Hindu India)

The Shore Temple at Mahabalipuram stands as a testament to the pioneering genius of Pallava architecture and represents one of India’s earliest experiments in structural stone temple construction. Built during the reign of Narasimhavarman II (700-728 CE), this temple marks the transition from rock-cut cave architecture to freestanding stone temples, establishing architectural principles that would influence South Indian temple construction for centuries.

What makes the Shore Temple architecturally revolutionary is its unique triple-shrine configuration. Two shrines house Shiva lingams – one facing east toward the rising sun, another facing west toward the setting sun – while a central shrine contains Vishnu in Anantashayana pose. This arrangement creates a complex theological program that honors both major Hindu traditions while demonstrating the Pallava commitment to religious synthesis.

The temple’s coastal location demanded innovative engineering solutions that showcase Pallava architectural sophistication. Built to withstand Bay of Bengal storms and salt-air erosion, the temple employs massive granite blocks fitted with extraordinary precision. The structural system, using post-and-lintel construction with corbelled roofing, demonstrates advanced understanding of load distribution and environmental resistance that enabled the temple’s survival for over 1,300 years.

The architectural elements establish the fundamental Dravidian vocabulary that would define South Indian temple construction. The pyramidal vimanas with their stepped profile, the pillared mandapas with their characteristic bracket capitals, and the integration of subsidiary shrines within a walled complex became standard features of later Tamil temple architecture. The temple functions as an architectural prototype, preserving early solutions to design problems that would be refined by subsequent dynasties.

The sculptural program reveals the sophisticated iconographic planning that characterizes Pallava art. The walls feature large-scale relief sculptures including Durga Mahishasuramardini, Vishnu Anantashayana, and numerous attendant deities carved with the naturalistic style that became the hallmark of Pallava sculpture. The integration of architectural and sculptural elements creates unified compositions that balance structural necessity with artistic expression.

The temple’s urban integration within the broader Mahabalipuram complex demonstrates Pallava understanding of architectural planning on multiple scales. The Shore Temple anchors the southern end of the site, creating visual and ceremonial connections with the cave temples, monolithic rathas, and the famous Arjuna’s Penance relief. This comprehensive approach to site planning influenced later South Indian temple complexes and established principles of sacred landscape design.

The temple’s current archaeological status provides unique insights into Pallava construction techniques and decorative programs. Recent excavations have revealed additional subsidiary shrines and defensive walls, suggesting the original complex was more extensive than previously understood. The temple continues to yield information about early Dravidian architecture, making it an invaluable resource for understanding the evolution of South Indian temple construction.

Summary:

- Built by Pallava king Narasimhavarman II (700-728 CE)

- Features unique triple-shrine configuration with dual Shiva and one Vishnu temple

- Pioneered structural stone temple construction in South India

- Demonstrates advanced coastal engineering and environmental resistance

- Establishes fundamental Dravidian architectural vocabulary

- Functions as architectural prototype influencing later Tamil temples

Conclusion

After two decades of studying these magnificent Architectural Marvels of Hindu India (Angkor Wat in Cambodia, but a Hindu temple), walking through their sacred courtyards at dawn and dusk, measuring their proportions, and deciphering their sculptural programs, I remain continually amazed by the architectural genius they represent. These ten temples are not merely buildings – they are crystallized prayers, solidified philosophies, and eternally preserved moments of human creative achievement that continue to inspire wonder more than a millennium after their creation.

The evolution from the cave temples of Ellora to the towering gopurams of Madurai, from the sensual sculptures of Khajuraho to the acoustic marvels of Hampi, reveals a continuous tradition of architectural innovation that spans centuries and dynasties while maintaining underlying principles of cosmic symbolism and spiritual purpose. Each monument represents a unique solution to the fundamental challenge of Hindu temple architecture: how to create earthly structures that embody divine presence and facilitate the human encounter with the sacred.

The technical achievements preserved in these monuments – the acoustic engineering of Vitthala’s musical pillars, the astronomical precision of Konark’s sundial wheels, the structural audacity of Kailasa’s monolithic carving, the urban integration of Meenakshi’s sacred geography – demonstrate levels of scientific and mathematical sophistication that rival modern engineering capabilities. These are not primitive structures built by ancient peoples, but sophisticated architectural instruments created by civilizations that understood the deepest principles of physics, mathematics, astronomy, and human psychology.

Perhaps most remarkably, these monuments continue to function as living temples, serving the spiritual needs of millions of devotees while preserving ancient wisdom traditions. The daily rituals at Jagannath Temple, the annual festivals at Meenakshi Temple, the continuing pilgrimage to Khajuraho – all testify to the enduring power of great architecture to connect past and present, human and divine, temporal and eternal.

The regional diversity represented by these monuments – from the Nagara traditions of central India to the Dravidian masterpieces of the south, from the Kalinga innovations of the east to the syncretic experiments of the Deccan – reveals the extraordinary creativity and adaptability of Hindu architectural traditions. Each region developed distinctive solutions while contributing to a shared architectural vocabulary that spread throughout the subcontinent and beyond to Southeast Asia.

The survival of these monuments through centuries of natural disasters, political upheavals, and cultural changes demonstrates both the physical durability of their construction and the spiritual durability of the traditions they embody. They stand as eternal testimonies to the human capacity for transcendence, creativity, and devotion – monuments that elevate the human spirit through the pure power of architectural beauty and spiritual significance.

For contemporary architects and planners, these temples offer invaluable lessons in sustainable construction, climate-responsive design, community integration, and the creation of spaces that serve both functional and transcendent purposes. They remind us that architecture at its highest level is not merely about shelter or aesthetics, but about creating environments that nurture human dignity and facilitate our deepest spiritual aspirations.

As I conclude this journey through India’s greatest architectural treasures, I am reminded that these monuments belong not just to India or to Hinduism, but to all humanity. They represent peaks of human achievement that inspire us to reach beyond the ordinary, to create with devotion and precision, and to build for eternity rather than mere convenience. In an age of rapid change and disposable construction, they stand as eternal reminders of what becomes possible when technical mastery serves transcendent purpose, when individual creativity contributes to collective achievement, and when human hands guided by spiritual vision transform stone into prayers that will echo through the centuries.

10 Architectural Marvels of Hindu India. Architectural Marvels of Hindu India.