The history of the Americas is a saga of exploration, conquest, resilience, and revolution. From the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492 to the formation of the United States of America, this journey witnessed the rise and fall of empires, the displacement of indigenous peoples, and the birth of a new nation that would shape the world.

Before European explorers set foot on the shores of the Americas, these lands were already home to diverse and sophisticated civilizations. The indigenous peoples of North and South America had established intricate societies, governed vast territories, and developed advanced agricultural, trade, and cultural systems. The Maya, Aztec, and Inca empires flourished in Central and South America, while the Mississippian culture, the Iroquois Confederacy, and the Pueblo peoples thrived in North America.

The arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492 marked the beginning of a new era—one of European exploration, colonization, and conquest. Seeking a direct trade route to Asia, Columbus, under the patronage of Spain, instead stumbled upon the Caribbean islands, unknowingly setting the stage for centuries of European involvement in the New World. His voyages opened the floodgates for explorers, traders, and settlers from Spain, Portugal, England, France, and the Netherlands, each vying for control over the newly discovered lands and their abundant resources.

This period of exploration and conquest led to the dramatic reshaping of the Americas. European powers established settlements, exploited natural wealth, and engaged in the transatlantic slave trade, bringing millions of Africans to work on plantations. Meanwhile, indigenous populations faced devastating consequences—war, displacement, and disease ravaged their communities, reducing their numbers drastically.

Also Read: The American Revolution (1775–1783) and Birth of America

As European colonies expanded, tensions grew between colonial settlers and their ruling nations. By the 18th century, British colonial subjects in North America began to resist increasing taxation and control imposed by the British Crown. The growing demand for representation and autonomy ignited a revolutionary spirit that would culminate in the American Revolution.

From the first explorations of the New World to the Declaration of Independence and the birth of the United States, the early history of the Americas is a testament to human ambition, resilience, and the enduring fight for freedom. This blog post explores the defining moments of this transformative era, shedding light on the events, conflicts, and individuals who shaped the continent’s history.

Explore the epic journey of America | History of the Americas

1. The Age of Exploration and European Discovery

America Before European Arrival

Long before the arrival of European explorers, North America was home to a vast array of indigenous civilizations. These societies thrived for thousands of years, establishing complex systems of governance, trade, agriculture, and culture that shaped the continent. The Iroquois Confederacy in the Northeast, for instance, created a sophisticated political alliance that influenced democratic principles. The Mississippian cultures in the central regions built expansive trade networks and large ceremonial cities such as Cahokia. In the Southwest, the Pueblo peoples constructed intricate cliff dwellings, while the Lakota and Cheyenne of the Great Plains developed a deep connection with the land, relying on buffalo for sustenance and tools.

The indigenous peoples of the Americas had lived in balance with nature, adapting to their diverse environments and creating societies rich in tradition, innovation, and resilience. However, the 15th and 16th centuries marked the beginning of an era that would forever alter the fate of these civilizations—the Age of Exploration. As European powers sought new trade routes, territories, and wealth, their expeditions led to the discovery and eventual colonization of the Americas.

Leif Erikson and the Norse Exploration

One of the earliest recorded European explorers to reach North America was the Norse navigator Leif Erikson, nearly 500 years before Columbus. Around the year 1000, Erikson and his crew sailed westward from Greenland and established a small settlement in what is now Labrador, Canada. This settlement, known as Vinland, was believed to be rich in timber, fish, and game. However, due to conflicts with indigenous peoples and harsh environmental conditions, the Norse presence in North America was short-lived. Their settlements were abandoned within a few decades, and their discoveries remained largely unknown to the rest of Europe. Despite their early arrival, the Norse did not establish long-term colonies or alter the course of history in the Americas.

Christopher Columbus and the Spanish Quest for New Lands

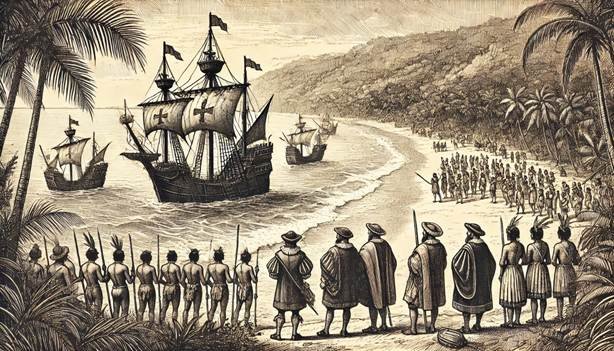

By the late 15th century, European nations—particularly Spain and Portugal—were in fierce competition to find new trade routes to Asia. In 1492, an ambitious Genoese explorer named Christopher Columbus, under the sponsorship of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain, set sail across the Atlantic with three ships: the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María. Unlike Erikson, Columbus was unaware of the existence of the American continents and sought a direct westward route to the lucrative spice markets of India and China.

On October 12, 1492, after over two months at sea, Columbus and his crew made landfall in the Caribbean, on an island in the Bahamas, which he named San Salvador. Believing he had reached islands off the coast of Asia, Columbus explored the region extensively, making contact with the indigenous Taino people and claiming the lands for Spain. His expeditions, which included three subsequent voyages, led to widespread European awareness of the “New World.”

Though Columbus never set foot on the mainland of North America, his voyages marked the beginning of European colonization and the transatlantic exchange of goods, people, and ideas. The Spanish Crown quickly realized the economic and strategic potential of these new lands, leading to an era of aggressive exploration, conquest, and colonization.

Also Read: The American Revolution (1775–1783) and Birth of America

European Powers Enter the Race for the New World

Following Columbus’ voyages, other European nations launched their own expeditions, eager to establish footholds in the Americas:

- Spain: After Columbus, Spanish explorers such as Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro led expeditions that conquered vast indigenous empires in Mexico and Peru, establishing Spanish dominance over large portions of the New World.

- Portugal: Focused more on South America, Portugal laid claim to Brazil, where they established sugar plantations and engaged in the transatlantic slave trade.

- France: French explorers like Jacques Cartier and Samuel de Champlain explored Canada and the St. Lawrence River, establishing the foundation for New France.

- England: In 1497, John Cabot, an Italian explorer sailing under the English flag, reached the coast of Newfoundland. Though England would not establish a permanent colony until the early 1600s, Cabot’s discovery laid the groundwork for future English claims in North America.

- The Netherlands and Sweden: These nations also sought to establish settlements in the Americas, though they had less lasting influence compared to Spain, England, and France.

The period of exploration in the 15th and 16th centuries was driven not only by the desire for land but also by the economic promise of resources such as gold, silver, furs, and spices. European explorers often relied on trade, alliances, and, at times, military conquest to establish their influence.

Impact on Indigenous Peoples

The arrival of Europeans brought immense suffering to the indigenous peoples of the Americas. Diseases such as smallpox, measles, and influenza—to which Native Americans had no immunity—decimated their populations. Some estimates suggest that within the first century of contact, nearly 90% of indigenous populations in some areas perished due to disease.

Additionally, European colonization led to violent conflicts as settlers encroached on native lands. Some indigenous groups attempted to form alliances with European powers, while others resisted colonization through warfare and rebellion. Despite these efforts, the vast technological advantages of European explorers and the introduction of firearms gave them an overwhelming edge in conquest.

The Age of Exploration fundamentally reshaped the Americas. What began as a quest for new trade routes ended with the transformation of entire continents. European settlements grew into powerful colonies, indigenous civilizations were displaced or destroyed, and a global network of trade and migration was established.

As the European powers expanded their presence in the New World, the stage was set for further conflict, colonization, and the eventual rise of new nations—including what would later become the United States.

2: The Race for Colonization

The discovery of the Americas set off a fierce competition among European powers eager to expand their influence, wealth, and territories. Spain, Portugal, France, England, the Netherlands, and Sweden all entered the race, each striving to establish settlements, trade routes, and colonies in the New World. The race for colonization was not just a battle for land—it was a struggle for economic dominance, religious expansion, and geopolitical power. However, this competition came at a tremendous cost to the indigenous peoples of North America, whose lands, cultures, and lives were irrevocably changed.

The First European Attempts at Colonization

Although Christopher Columbus’ voyages in the late 15th century sparked European interest in the Americas, he was not the first European to reach North America. Leif Erikson and the Norse explorers had arrived nearly 500 years earlier. Around the year 1000 AD, Erikson and his crew established Vinland, a short-lived Norse settlement in present-day Newfoundland, Canada. However, due to harsh weather, limited resources, and conflicts with the indigenous peoples, the settlement was abandoned.

Despite this early contact, large-scale European colonization did not begin until the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The Spanish and Portuguese were the first to make lasting claims in the Americas, followed by the French, English, Dutch, and Swedes.

Spanish Colonization (1500s)

Spain was the dominant colonial power in the Americas during the 16th century. Following Columbus’ voyages, the Spanish Crown sought to expand its empire, sending conquistadors to explore and conquer vast regions. Their primary goals were the three Gs—Gold, Glory, and God.

Key Spanish Expeditions

- Juan Ponce de León (1513) – Explored and named Florida, searching for the legendary “Fountain of Youth.”

- Hernando de Soto (1539-1542) – Traveled through the southeastern United States, crossing the Mississippi River.

- Francisco Vázquez de Coronado (1540-1542) – Explored the American Southwest in search of the fabled “Seven Cities of Gold.”

Spain’s primary focus was on South America, the Caribbean, and Mexico, where they established colonies, extracted vast amounts of gold and silver, and forced indigenous populations into labor through the encomienda system. However, they also claimed parts of North America, particularly Florida and the Southwest. St. Augustine, Florida, founded in 1565, became the first permanent European settlement in what is now the United States.

Spain’s colonization was marked by brutal conquest and cultural imposition. The indigenous civilizations of the Aztecs and Incas were destroyed, and millions of Native Americans perished due to warfare and diseases such as smallpox.

French and Dutch Explorations (1600s)

Unlike Spain, which sought conquest and wealth, France and the Netherlands focused on trade, particularly in furs.

French Colonization

The French established their presence in Canada and the Great Lakes region, relying on alliances with Native American tribes to establish a thriving fur trade.

- Jacques Cartier (1534-1541) – Explored the St. Lawrence River and claimed the region for France.

- Samuel de Champlain (1608) – Founded Quebec, the first permanent French settlement in North America.

- René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (1682) – Explored the Mississippi River, claiming the vast Louisiana Territory for France.

The French maintained relatively peaceful relations with Native Americans compared to the Spanish and English, focusing on trade partnerships rather than outright conquest.

Dutch Colonization

The Dutch, known for their powerful maritime trade network, established settlements along the Hudson River in present-day New York.

- Henry Hudson (1609) – Explored the river that now bears his name, paving the way for Dutch claims.

- New Amsterdam (1624) – A major fur trading post, later renamed New York after the British took control in 1664.

The Dutch encouraged diverse settlement, welcoming people from various European backgrounds. However, their colonies were relatively small and eventually fell to English control.

English Colonization (1607-1620s)

England was relatively late to the race for colonization, but it ultimately became the dominant colonial power in North America. English settlements were driven by a combination of economic ambition, religious freedom, and strategic expansion.

Early English Settlements

- Roanoke Colony (1585 & 1587) – Established in present-day North Carolina, Roanoke mysteriously disappeared, earning the title of the “Lost Colony.”

- Jamestown, Virginia (1607) – The first permanent English settlement in North America, founded by the Virginia Company. The colony struggled with disease, famine, and conflict with the Powhatan Confederacy but survived due to tobacco cultivation.

- Plymouth Colony (1620) – Founded by the Pilgrims, a group of religious separatists who sought freedom from the Church of England. Their survival was aided by Native Americans like Squanto, leading to the first Thanksgiving in 1621.

Unlike Spain and France, England encouraged large-scale migration, leading to the establishment of the Thirteen Colonies along the East Coast.

Also Read: The American Revolution (1775–1783) and Birth of America

The Swedish and Russian Presence

Though often overlooked, Sweden and Russia also had brief colonial ambitions in North America.

- New Sweden (1638-1655) – A Swedish colony in present-day Delaware and Pennsylvania, later absorbed by the Dutch.

- Russian Alaska (1741-1867) – The Russians established fur trading posts along the Pacific Northwest, with Sitka, Alaska, serving as their colonial capital.

Conflicts and Consequences of Colonization

The European competition for land and resources inevitably led to conflict—both among European nations and with indigenous peoples.

European Rivalries

As European settlements expanded, tensions arose:

- The Anglo-Spanish War (1585-1604) saw Spain and England battling for dominance in the Atlantic.

- The Beaver Wars (1609-1701) involved France and its Native allies fighting against the Iroquois Confederacy for control of the fur trade.

- The Dutch-English Wars (1652-1674) led to the Dutch ceding New Amsterdam to England.

Impact on Indigenous Peoples

- European diseases wiped out millions of Native Americans.

- Indigenous lands were seized, and many tribes were forced to relocate or assimilate.

- Some tribes, like the Iroquois Confederacy, used European alliances to expand their own power.

The Race That Changed the World

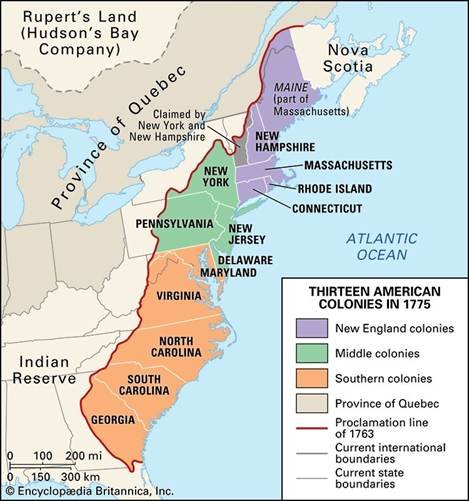

By the late 1600s, European powers had carved up vast territories in North America. Spain controlled the Southwest and Florida, France dominated Canada and Louisiana, England established the Thirteen Colonies, and the Dutch and Swedish settlements had been absorbed into larger empires.

This competition for land and resources laid the groundwork for future conflicts, including the French and Indian War (1754-1763) and, eventually, the American Revolution (1775-1783).

The race for colonization forever altered the fate of North America. It reshaped indigenous societies, fueled the global economy, and set the stage for centuries of conflict, migration, and cultural exchange.

Despite the suffering it caused, the colonial era defined the modern world, leaving behind a legacy that still shapes nations today.

3: Expansion, Conflict, and the Formation of the Thirteen Colonies

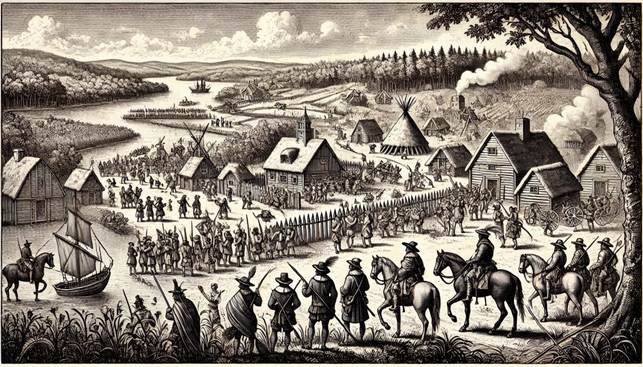

By the early 17th century, European powers had established a strong foothold in North America. The English, French, Dutch, and Spanish all laid claim to territories, each pursuing their own vision of colonization. England, however, emerged as the dominant force along the eastern seaboard, steadily expanding its settlements and establishing what would become the Thirteen Colonies. This period of expansion was marked by economic growth, political evolution, and increasing tensions—both between European powers and between settlers and Native American nations.

The expansion of European settlements came at a tremendous cost to indigenous populations. Diseases introduced by Europeans, combined with warfare and displacement, devastated Native American communities. The struggle for land and resources led to violent conflicts, shaping the future of North America and laying the foundation for the eventual rise of the United States.

The Formation of the Thirteen Colonies

During the 1600s, England established a series of permanent colonies along the Atlantic coast. Each colony developed distinct economic, social, and political structures, but they all shared a common allegiance to the English Crown.

Early English Colonies and Their Growth

- Virginia (1607): The first permanent English settlement, Jamestown, was established by the Virginia Company. Tobacco cultivation, introduced by John Rolfe, became the economic backbone of the colony.

- Massachusetts (1620): Founded by the Pilgrims at Plymouth and later expanded by the Puritans in Boston (1630), Massachusetts became a center for religious freedom and self-governance.

- Maryland (1634): Established as a haven for Catholics by Lord Baltimore, Maryland became known for its policy of religious tolerance.

- Rhode Island (1636): Founded by Roger Williams, Rhode Island promoted religious freedom and fair treatment of Native Americans.

- Connecticut (1636): Established by Puritan settlers seeking more autonomy from Massachusetts, Connecticut developed the first written constitution in America (Fundamental Orders of Connecticut).

- New York (1664): Originally a Dutch colony (New Amsterdam), it was seized by the English and renamed New York.

- Pennsylvania (1681): Founded by William Penn as a Quaker colony, Pennsylvania became known for religious tolerance and fair dealings with Native Americans.

- Georgia (1732): The last of the Thirteen Colonies, Georgia was established as a buffer against Spanish Florida and a haven for debtors and the poor.

Over time, these colonies became economically diverse—New England focused on shipbuilding and trade, the Middle Colonies thrived on agriculture and commerce, and the Southern Colonies relied on slave-based plantation economies growing tobacco, rice, and indigo.

Also Read: The American Revolution (1775–1783) and Birth of America

Conflicts with Native Americans

As English settlers expanded westward, they came into direct conflict with indigenous nations. Unlike the French, who built trade relationships with Native Americans, the English often viewed land as property to be owned and cultivated, leading to numerous territorial disputes.

Key Native American Conflicts

1. Anglo-Powhatan Wars (1610-1646)

- Fought between English settlers in Virginia and the Powhatan Confederacy, led by Chief Powhatan.

- The first war (1610-1614) ended with the marriage of Pocahontas to John Rolfe, creating temporary peace.

- A second war (1622-1632) erupted when Powhatan warriors launched a surprise attack, killing hundreds of settlers.

- The third war (1644-1646) resulted in the near destruction of the Powhatan people and solidified English control over Virginia.

2. Pequot War (1636-1638)

- A violent conflict between New England settlers and the Pequot tribe in Connecticut.

- The war ended with the Mystic Massacre, where an entire Pequot village was set on fire, killing hundreds of men, women, and children.

- Survivors were enslaved or forced to join other tribes.

3. King Philip’s War (1675-1678)

- One of the bloodiest conflicts in early American history, fought between New England settlers and an alliance of Native American tribes led by Metacom (“King Philip”), the Wampanoag leader.

- The war resulted from rising tensions over land encroachment and broken treaties.

- Native forces attacked over 50 English settlements, causing widespread destruction.

- The war ended with Metacom’s death, and Native American resistance in New England was permanently weakened.

- Thousands of Native Americans were killed, enslaved, or displaced, while English settlements continued to expand.

Rivalries Among European Powers

The competition for dominance in North America led to frequent conflicts between European nations. While Spain focused on the Southwest and Florida, England and France fought bitterly over territory and trade.

1. The Dutch-English Rivalry

- The Dutch originally controlled New Netherland (modern-day New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Connecticut).

- In 1664, England seized New Amsterdam, renaming it New York after the Duke of York.

- Dutch influence gradually declined, and New Netherland became an English-controlled colony.

2. The French and Indian War (1754-1763)

- A major conflict between Britain and France, fought in North America, Europe, and India.

- Known in Europe as the Seven Years’ War, this war determined control of North America.

- The war began over competition in the Ohio River Valley, where both the British and French claimed the land.

- Key Events:

- Battle of Fort Duquesne (1755): British defeat at the hands of French and Native American forces.

- Battle of Quebec (1759): A British victory that led to the fall of French Canada.

- Treaty of Paris (1763): Ended the war, giving Britain control of Canada and all French territories east of the Mississippi River.

- The war strengthened British dominance but left Britain in deep debt, leading to heavy taxation on the colonies—a major cause of the American Revolution.

Social and Political Evolution in the Colonies

Self-Governance and Democracy

- The colonies gradually developed self-rule, laying the groundwork for American democracy.

- The Mayflower Compact (1620) was the first governing document in America, establishing the idea of self-government.

- The House of Burgesses (1619) in Virginia was the first elected legislature in the colonies.

- Town Meetings in New England allowed settlers to participate in local governance.

Religious Movements

- The Great Awakening (1730s-1740s) was a religious revival that promoted individual faith and resistance to authority, planting the seeds for future revolutionary thought.

- Religious diversity flourished, particularly in Rhode Island and Pennsylvania, which welcomed settlers of different faiths.

The Foundation of a New Nation

By the mid-18th century, the Thirteen Colonies had evolved into a diverse and economically powerful region. However, conflicts with Native Americans, competition with European rivals, and discontent with British rule were all growing.

The French and Indian War had eliminated France as a colonial power, but Britain’s increasing control and taxation would spark resentment among colonists. As the colonies expanded, so did their desire for independence, setting the stage for the American Revolution.

The transformation of these settlements into a unified nation was still decades away, but the foundations of democracy, self-governance, and resistance were already taking root. The next chapter in America’s story would be one of revolution, rebellion, and the birth of a new nation.

4: The Road to Revolution

The mid-18th century was a turning point in the relationship between Britain and its American colonies. The British government, burdened by enormous debts from the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), looked to the American colonies as a source of revenue. However, the policies they implemented to extract this revenue were met with fierce resistance. Over the next decade, the colonies transitioned from isolated acts of defiance to organized rebellion, setting the stage for war.

Economic Strains and Colonial Grievances

Following the Seven Years’ War, Britain found itself in financial distress, with war debts totaling over £122 million. The cost of maintaining troops in North America added further strain to the British treasury. In an effort to share these financial burdens, Britain introduced a series of taxes and regulations on the American colonies. However, these measures fundamentally altered the previously lax relationship between the colonies and the Crown.

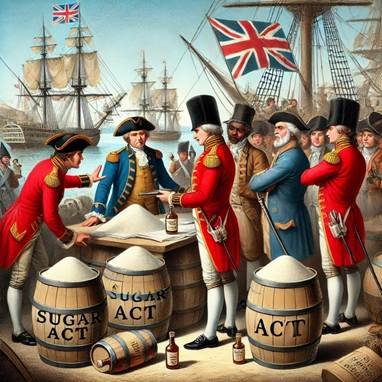

The Sugar Act (1764): The First Step Toward Conflict

The Sugar Act of 1764 was the first major attempt to directly tax the colonies. It reduced the tax on molasses imported from the Caribbean but strictly enforced the collection of these duties, ending the practice of widespread smuggling. The act also imposed new taxes on sugar, coffee, indigo, and wine.

The Sugar Act had several major consequences:

- It hurt colonial merchants, particularly in New England, who had long relied on smuggling.

- It gave British naval officers and customs officials broad powers to search ships and confiscate goods, creating resentment among colonial traders.

- It set the precedent for Parliament taxing the colonies without their consent.

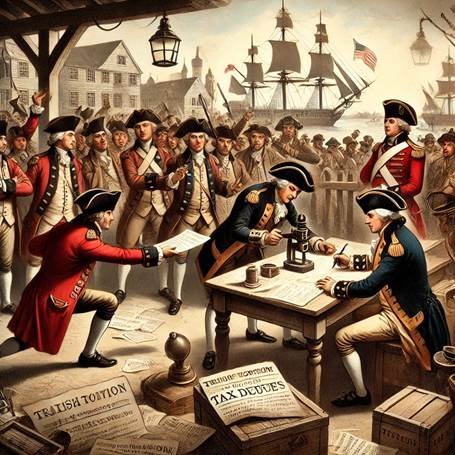

The Stamp Act (1765): A Turning Point

In 1765, the Stamp Act was introduced, requiring that many printed materials—including newspapers, legal documents, licenses, and playing cards—bear an official British stamp. Unlike the Sugar Act, which targeted merchants, the Stamp Act affected almost every colonist, from lawyers and printers to farmers and laborers.

Colonists viewed this as direct taxation without representation, as they had no elected representatives in the British Parliament. Resistance quickly spread:

- Patrick Henry delivered his famous speech in the Virginia House of Burgesses, condemning the tax and declaring, “If this be treason, make the most of it!”

- Secret groups like the Sons of Liberty formed to resist British policies, using intimidation and violence against British tax collectors.

- Colonial merchants boycotted British goods, leading to economic pressure on British businesses.

Faced with fierce opposition, Britain repealed the Stamp Act in 1766, but it simultaneously passed the Declaratory Act, asserting its right to legislate for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”

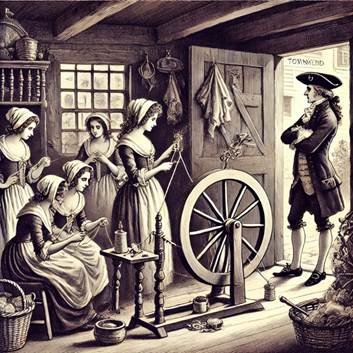

The Townshend Acts (1767): Renewed Tensions

In 1767, Britain introduced the Townshend Acts, which placed duties on goods such as glass, lead, paper, paint, and tea. The British government also stationed troops in Boston to enforce the collection of taxes.

The colonies responded with renewed protests and boycotts, which were largely led by women, who refused to purchase British textiles and instead spun their own cloth in what became known as the Daughters of Liberty movement. Resistance escalated into direct confrontations with British troops.

From Protests to Violence: The Boston Massacre (1770)

The presence of British soldiers in Boston heightened tensions, leading to frequent street clashes between colonists and British troops. On March 5, 1770, an argument between a British soldier and a Bostonian escalated into violence. A crowd of colonists began taunting and throwing snowballs mixed with ice and rocks at a group of British soldiers. In the chaos, British troops opened fire, killing five colonists, including Crispus Attucks, a man of African and Native American descent.

Although only a handful of people died, the Boston Massacre was widely used as propaganda by leaders like Samuel Adams and Paul Revere, who depicted the event as an unprovoked slaughter of innocent civilians.

The Tea Crisis and the Boston Tea Party (1773)

Despite repealing most of the Townshend duties, Britain kept the tax on tea to assert its authority. In 1773, the Tea Act allowed the struggling British East India Company to sell surplus tea directly to the American colonies at a discounted rate. Although the act actually lowered the price of tea, it cut colonial merchants out of the trade, angering many.

In response, on the night of December 16, 1773, a group of American patriots disguised as Mohawk Indians boarded three British ships in Boston Harbor and dumped 342 chests of tea into the water—an event that became known as the Boston Tea Party.

British Retaliation: The Intolerable Acts (1774)

Britain responded to the Tea Party with a set of harsh laws known in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts:

- The Boston Port Act closed Boston Harbor until the tea was paid for.

- The Massachusetts Government Act limited self-government by restricting town meetings.

- The Administration of Justice Act allowed British officials accused of crimes in the colonies to be tried in Britain.

- The Quartering Act required colonists to house British soldiers in their homes.

Instead of crushing the resistance, these laws united the colonies against Britain.

The First Continental Congress (1774): A United Response

In response to the Intolerable Acts, 12 of the 13 colonies sent delegates to the First Continental Congress, held in Philadelphia in September 1774. Here, colonial leaders such as John Adams, George Washington, and Patrick Henry debated the next course of action.

The Congress took several key steps:

- It called for a renewed boycott of British goods.

- It drafted the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, stating that the colonies had the right to govern themselves.

- It urged each colony to form militias in preparation for potential conflict.

Although some delegates hoped for reconciliation with Britain, others saw war as inevitable.

The Road to War: The Battles of Lexington and Concord (1775)

By early 1775, tensions had reached a breaking point. British military leaders, aware that colonists were stockpiling weapons, planned a raid on Concord, Massachusetts, to seize these supplies.

On April 18, 1775, British troops marched toward Concord, but Paul Revere and other riders spread the alarm with the famous warning: “The British are coming!”.

On April 19, 1775, British soldiers met local militiamen in Lexington. A shot rang out—later called the “shot heard ’round the world”—and the first battle of the American Revolution began.

Conclusion: The Revolution Begins

Over the course of a decade, Britain’s attempts to exert greater control over its American colonies had backfired, leading instead to a growing movement for independence. What had started as protests against taxation had now escalated into armed resistance.

The road to revolution was complete—the American colonies were now at war with the British Empire.

Key Takeaways

- Britain imposed taxes (Sugar Act, Stamp Act, Townshend Acts) to pay war debts.

- Colonists resisted taxation, demanding representation in Parliament.

- Violence erupted in the Boston Massacre (1770).

- The Boston Tea Party (1773) led to harsh British retaliation (Intolerable Acts).

- The First Continental Congress (1774) organized resistance.

- The first shots of the Revolution were fired at Lexington and Concord (1775).

YouTube Hindi Channel Link:

YouTube English Channel Link:

YouTube Channel Link:

YouTube Channel Link