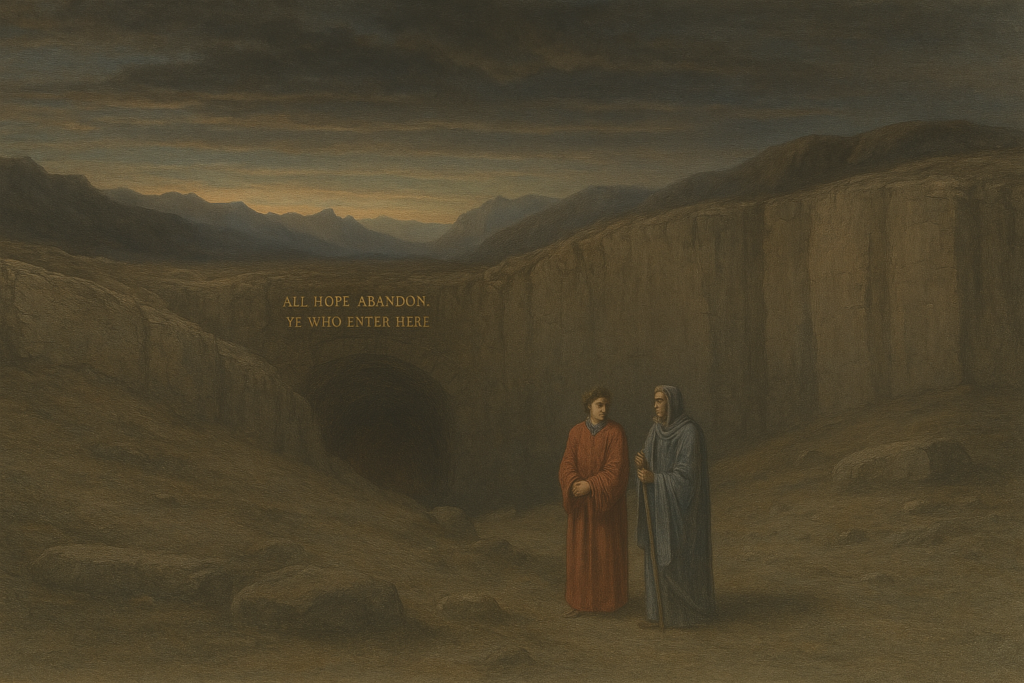

The Divine Comedy – Inferno: Canto 3 takes you to the gates of Hell, where haunting words echo, and lost souls wander in endless sorrow. Let us explore the poem “Inferno: Canto 3” by Dante Alighieri. Inferno is a part of Dante’s Poem “Divine Comedy” and is the first part.

In this powerful canto, Dante stands before the gates of Hell — a place marked not just by fire, but by a deep and sorrowful silence. Inscribed above the entrance are words that shake the soul: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” What follows is a descent into a realm where the consequences of a life without purpose, faith, or direction are laid bare.

Guided by the steadfast Virgil, Dante crosses the threshold and begins to witness the fate of those who never chose — the indifferent, the apathetic, the ones who lived without making a stand for good or evil. These souls swirl endlessly, denied even the dignity of a place in Hell proper. It’s a sobering look at spiritual emptiness, painted with vivid imagery and piercing truth.

Canto 3 isn’t just about Hell — it’s about the weight of choice, the cost of inaction, and the sorrow of wasted potential. It sets the tone for the journey ahead: one that challenges not just the poet, but every reader, to examine their own path.

To get the context you must explore: Dante Alighieri Inferno and read 3 Parts of Divine Comedy,

Now let us move with The Divine Comedy – Inferno: Canto 3 and look into the Poem, Summary, and Analysis.

Table of Contents

The Divine Comedy – Inferno: Canto 3 – Poem

“Through me you pass into the city of woe:

~ The Divine Comedy – Inferno: Canto 3 (Dante Alighieri)

Through me you pass into eternal pain:

Through me among the people lost for aye.

Justice the founder of my fabric mov’d:

To rear me was the task of power divine,

Supremest wisdom, and primeval love.

Before me things create were none, save things

Eternal, and eternal I endure.

“All hope abandon ye who enter here.”

Such characters in colour dim I mark’d

Over a portal’s lofty arch inscrib’d:

Whereat I thus: “Master, these words import

Hard meaning.” He as one prepar’d replied:

“Here thou must all distrust behind thee leave;

Here be vile fear extinguish’d. We are come

Where I have told thee we shall see the souls

To misery doom’d, who intellectual good

Have lost.” And when his hand he had stretch’d forth

To mine, with pleasant looks, whence I was cheer’d,

Into that secret place he led me on.

Here sighs with lamentations and loud moans

Resounded through the air pierc’d by no star,

That e’en I wept at entering. Various tongues,

Horrible languages, outcries of woe,

Accents of anger, voices deep and hoarse,

With hands together smote that swell’d the sounds,

Made up a tumult, that for ever whirls

Round through that air with solid darkness stain’d,

Like to the sand that in the whirlwind flies.

I then, with error yet encompass’d, cried:

“O master! What is this I hear? What race

Are these, who seem so overcome with woe?”

He thus to me: “This miserable fate

Suffer the wretched souls of those, who liv’d

Without or praise or blame, with that ill band

Of angels mix’d, who nor rebellious prov’d

Nor yet were true to God, but for themselves

Were only. From his bounds Heaven drove them forth,

Not to impair his lustre, nor the depth

Of Hell receives them, lest th’ accursed tribe

Should glory thence with exultation vain.”

I then: “Master! what doth aggrieve them thus,

That they lament so loud?” He straight replied:

“That will I tell thee briefly. These of death

No hope may entertain: and their blind life

So meanly passes, that all other lots

They envy. Fame of them the world hath none,

Nor suffers; mercy and justice scorn them both.

Speak not of them, but look, and pass them by.”

And I, who straightway look’d, beheld a flag,

Which whirling ran around so rapidly,

That it no pause obtain’d: and following came

Such a long train of spirits, I should ne’er

Have thought, that death so many had despoil’d.

When some of these I recogniz’d, I saw

And knew the shade of him, who to base fear

Yielding, abjur’d his high estate. Forthwith

I understood for certain this the tribe

Of those ill spirits both to God displeasing

And to his foes. These wretches, who ne’er lived,

Went on in nakedness, and sorely stung

By wasps and hornets, which bedew’d their cheeks

With blood, that mix’d with tears dropp’d to their feet,

And by disgustful worms was gather’d there.

Then looking farther onwards I beheld

A throng upon the shore of a great stream:

Whereat I thus: “Sir! grant me now to know

Whom here we view, and whence impell’d they seem

So eager to pass o’er, as I discern

Through the blear light?” He thus to me in few:

“This shalt thou know, soon as our steps arrive

Beside the woeful tide of Acheron.”

Then with eyes downward cast and fill’d with shame,

Fearing my words offensive to his ear,

Till we had reach’d the river, I from speech

Abstain’d. And lo! toward us in a bark

Comes on an old man hoary white with eld,

Crying, “Woe to you wicked spirits! hope not

Ever to see the sky again. I come

To take you to the other shore across,

Into eternal darkness, there to dwell

In fierce heat and in ice. And thou, who there

Standest, live spirit! get thee hence, and leave

These who are dead.” But soon as he beheld

I left them not, “By other way,” said he,

“By other haven shalt thou come to shore,

Not by this passage; thee a nimbler boat

Must carry.” Then to him thus spake my guide:

“Charon! thyself torment not: so ’t is will’d,

Where will and power are one: ask thou no more.”

Straightway in silence fell the shaggy cheeks

Of him the boatman o’er the livid lake,

Around whose eyes glar’d wheeling flames. Meanwhile

Those spirits, faint and naked, color chang’d,

And gnash’d their teeth, soon as the cruel words

They heard. God and their parents they blasphem’d,

The human kind, the place, the time, and seed

That did engender them and give them birth.

Then all together sorely wailing drew

To the curs’d strand, that every man must pass

Who fears not God. Charon, demoniac form,

With eyes of burning coal, collects them all,

Beck’ning, and each, that lingers, with his oar

Strikes. As fall off the light autumnal leaves,

One still another following, till the bough

Strews all its honours on the earth beneath;

E’en in like manner Adam’s evil brood

Cast themselves one by one down from the shore,

Each at a beck, as falcon at his call.

hus go they over through the umber’d wave,

And ever they on the opposing bank

Be landed, on this side another throng

Still gathers. “Son,” thus spake the courteous guide,

“Those, who die subject to the wrath of God,

All here together come from every clime,

And to o’erpass the river are not loth:

For so heaven’s justice goads them on, that fear

Is turn’d into desire. Hence ne’er hath past

Good spirit. If of thee Charon complain,

Now mayst thou know the import of his words.”

This said, the gloomy region trembling shook

So terribly, that yet with clammy dews

Fear chills my brow. The sad earth gave a blast,

That, lightening, shot forth a vermilion flame,

Which all my senses conquer’d quite, and I

Down dropp’d, as one with sudden slumber seiz’d.

Quoted from the public domain translation of Dante’s Inferno, available on Project Gutenberg.

The Divine Comedy – Inferno: Canto 3 Analysis and Interpretation

In Inferno: Canto 3, Dante and Virgil arrive at the gates of Hell, where the iconic inscription reads: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” This is the point of no return. Beyond the gate, they encounter the souls of the “neutral” — those who lived without committing to good or evil. These are the people who drifted through life without conviction, and now they drift in death, endlessly chasing a blank banner while being stung by insects — a punishment for their moral cowardice.

After witnessing this, Dante and Virgil approach the river Acheron, where the ferryman Charon waits. He angrily refuses to take Dante across because he is still alive. But Virgil explains that Dante’s journey has divine approval. As Dante loses consciousness from the overwhelming experience, the canto ends, and the deeper descent begins.

Analysis and Interpretation of Inferno: Canto 3 — Stanza 1

“Through me you pass into the city of woe:

Through me you pass into eternal pain:

Through me among the people lost for aye.

Justice the founder of my fabric mov’d:

To rear me was the task of power divine,

Supremest wisdom, and primeval love.

Before me things create were none, save things

Eternal, and eternal I endure.

“All hope abandon ye who enter here.”

Summary & Meaning:

This stanza is the inscription on the gate of Hell that Dante and Virgil encounter as they enter the infernal realm. It speaks of the inevitability and permanence of Hell, emphasizing that those who enter must leave all hope behind. The inscription mentions that the city of woe, where the damned reside forever, was constructed by divine justice, supreme wisdom, and love. It points to the eternal nature of the place and the eternal suffering awaiting all who enter.

Themes Introduced:

- Divine Justice and Judgment: The mention of “justice the founder of my fabric mov’d” reinforces the idea that Hell is a result of divine justice. All the damned souls are there due to their own choices and actions in life, and their punishment is just and eternal.

- Eternal Suffering: “Eternal pain” and the condemnation of souls to be “lost for aye” introduce the theme of eternal suffering in Hell, which cannot be escaped or undone.

- Hope Abandonment: The phrase “All hope abandon ye who enter here” sets the tone for the hopelessness that defines Hell, highlighting the absence of redemption for the souls trapped there.

Symbolism:

- The Gate of Hell: The gate symbolizes the irreversible nature of damnation. It is a threshold that once crossed, cannot be returned from, and it serves as a warning to all souls entering Hell.

- Justice, Wisdom, and Love: These divine attributes symbolize the fundamental principles that govern the universe. They are personified as the creators of Hell, suggesting that even punishment and suffering are ultimately rooted in a higher, divine order.

Tone & Mood:

- Tone: The tone is solemn, serious, and authoritative. It’s a divine proclamation, and it instills a sense of inevitability and finality. The tone reflects the gravity of the situation and the severity of what lies ahead.

- Mood: The mood is one of dread and despair. The inscription’s declaration that all hope must be abandoned creates a sense of hopelessness, making the reader (and Dante, the character) feel the weight of the eternal suffering to come.

This stanza sets the stage for the rest of Dante’s journey through Hell, marking it as a place of irreversible torment and divine justice.

Analysis and Interpretation of Inferno: Canto 3 — Stanza 2

Such characters in colour dim I mark’d

Over a portal’s lofty arch inscrib’d:

Whereat I thus: “Master, these words import

Hard meaning.” He as one prepar’d replied:

“Here thou must all distrust behind thee leave;

Here be vile fear extinguish’d. We are come

Where I have told thee we shall see the souls

To misery doom’d, who intellectual good

Have lost.” And when his hand he had stretch’d forth

To mine, with pleasant looks, whence I was cheer’d,

Into that secret place he led me on.

Summary & Meaning:

Dante reads the somber inscription above the gate of Hell and is struck by the weight of its meaning. He turns to Virgil, his guide, for reassurance. Virgil responds with calm resolve, instructing Dante to let go of all doubt and fear—emotions that have no place in their journey ahead. Virgil reminds him that they are about to witness the souls who are damned, those who have lost “intellectual good,” meaning divine reason or alignment with truth and God. With kindness and encouragement, Virgil reaches for Dante’s hand and leads him into the “secret place”—the dark, mysterious realm of Hell.

Themes Introduced:

- Courage in the Face of Fear: Dante’s reaction to the inscription is human—fearful and uncertain. Virgil urges him to abandon fear and distrust, a recurring theme throughout Inferno as Dante must steel himself for the horrors ahead.

- Loss of Divine Reason: Virgil mentions the souls who have lost “intellectual good,” introducing the theme of reason and its divine nature. Hell is not only a place for sinners but for those who turned away from truth and intellect as guided by God.

- Mentorship and Guidance: The bond between Dante and Virgil deepens. Virgil not only guides physically but also emotionally and spiritually, embodying the theme of wise mentorship leading a soul through darkness.

Symbolism:

- The Inscription: Again, symbolizing finality and the divine order, the gate and its grim warning contrast with Virgil’s calm demeanor. This contrast symbolizes the strength found in knowledge and faith over emotional panic.

- Virgil’s Hand: When Virgil extends his hand to Dante, it’s a symbolic gesture of support, mentorship, and reassurance. It reflects the guiding light of human reason (Virgil personifies reason) leading the soul (Dante) through confusion and fear.

- The “Secret Place”: This phrase elevates Hell to a mysterious, almost sacred space of divine justice—“secret” not in the sense of hidden but in the sense of holding great, dreadful truths.

Tone & Mood:

- Tone: The tone shifts from Dante’s initial anxiety and fear to a more comforting and steady tone through Virgil’s words. It reflects preparedness, resolve, and even warmth in the face of impending horror.

- Mood: The mood is tense yet oddly reassuring. There is unease as Dante prepares to enter Hell, but Virgil’s presence softens it with a sense of protection and calm resolve. The anticipation is heavy, but the guidance offers a thread of hope—even in a hopeless realm.

This passage beautifully shows the transition from fear to acceptance. Dante’s spiritual journey requires not just physical travel but emotional and moral fortitude—and Virgil, as reason and wisdom, becomes a comforting compass through the unknown.

Analysis and Interpretation of Inferno: Canto 3 — Stanza 3

Here sighs with lamentations and loud moans

Resounded through the air pierc’d by no star,

That e’en I wept at entering. Various tongues,

Horrible languages, outcries of woe,

Accents of anger, voices deep and hoarse,

With hands together smote that swell’d the sounds,

Made up a tumult, that for ever whirls

Round through that air with solid darkness stain’d,

Like to the sand that in the whirlwind flies.I then, with error yet encompass’d, cried:

“O master! What is this I hear? What race

Are these, who seem so overcome with woe?”

Summary & Meaning:

As Dante and Virgil step into Hell, they are immediately overwhelmed by a cacophony of suffering. The atmosphere is filled with sighs, wailing, and moans—echoes of eternal sorrow that move Dante to tears. In this gloomy, starless space, the very air is heavy with pain. The sounds come from a multitude of voices—spoken in different tongues, expressing anger, grief, and despair—all blending into an eternal, chaotic roar. Even the physical gestures of the damned—like clapping or wringing hands—add to the overwhelming noise.

Dante, still confused and emotional, turns to Virgil and asks: what is this place, and who are these tormented souls?

Themes Introduced:

- Universal Suffering: The chorus of sounds in many languages suggests that sin and its consequences are universal, not limited by geography or language. It reflects the global reach of human folly and divine justice.

- Emotional Vulnerability of the Soul: Dante’s weeping shows that the soul must confront horror and sorrow directly to grow. His journey through Hell isn’t just observation—it’s transformation through emotional exposure.

- Loss of Light and Hope: The air “pierced by no star” hints at total separation from divine guidance or grace. The absence of celestial bodies is symbolic of complete despair.

- Chaos and Disorder: The whirlwind of sounds and darkness represents spiritual confusion and disorder—souls who have lost their way, and now spin eternally in a tumult of meaninglessness.

Symbolism:

- The Soundscape of Hell: The overwhelming noise symbolizes the spiritual noise and disarray of souls disconnected from God. Unlike the harmony of Heaven, Hell is dissonance, filled with unresolved cries of regret and rage.

- Dark, Starless Sky: Stars in The Divine Comedy often represent divine hope or guidance. Their absence here symbolizes the absence of God’s light and direction—these souls are truly lost.

- Whirling Sand: The sand flying in a whirlwind likens the souls to particles, directionless and helpless, swept by forces they can no longer control—symbolizing the consequences of a life without moral grounding.

Tone & Mood:

- Tone: The tone is mournful and chaotic. Dante’s narration is full of sorrow and confusion, while the descriptions of the noise are relentless and disturbing.

- Mood: The mood is oppressive and overwhelming. The blend of noise, darkness, and emotional despair creates a sense of panic and helplessness, mirroring Dante’s inner state as he descends into the spiritual abyss.

This passage powerfully introduces us to the ambiguous souls—those not damned for specific sins but still denied Heaven for lacking moral conviction. It sets the tone for all that follows in Inferno: a world without hope, light, or silence, where punishment is not just physical, but deeply psychological and eternal.

Analysis and Interpretation of Inferno: Canto 3 — Stanza 4

He thus to me: “This miserable fate

Suffer the wretched souls of those, who liv’d

Without or praise or blame, with that ill band

Of angels mix’d, who nor rebellious prov’d

Nor yet were true to God, but for themselves

Were only. From his bounds Heaven drove them forth,

Not to impair his lustre, nor the depth

Of Hell receives them, lest th’ accursed tribe

Should glory thence with exultation vain.”

Summary & Meaning:

Virgil explains to Dante that the tormented souls they hear belong to the “neutrals”—those who lived without committing great sins, but also without standing for anything noble or good. These are the souls who existed only for themselves, never taking a stand for good or evil. Alongside them are the cowardly angels who, during Lucifer’s rebellion, chose neither to side with God nor rebel. Because of their indecision and selfishness, they are rejected from both Heaven and Hell. Heaven casts them out to preserve its purity, while even Hell refuses them, so they won’t give the damned cause for pride by associating with them.

Themes Introduced:

- Moral Indifference & Cowardice: This is a major theme in Dante’s moral universe. Neutrality in the face of moral conflict is not seen as harmless, but as contemptible. Choosing not to choose is, in Dante’s view, a profound spiritual failure.

- Consequences of Self-Centeredness: The souls who lived “for themselves only” represent those who refused to engage in life’s deeper meaning, seeking only personal safety, comfort, or gain. They are now condemned to an eternity of insignificance.

- Rejection by Both Realms: These souls are so lacking in substance that they don’t even earn a proper place in Hell. Their fate is to exist in limbo, erased from memory and divine recognition.

Symbolism:

- “That ill band of angels”: These angels are symbols of moral ambiguity, spiritual apathy, and the dangers of neutrality in moral conflict. They are the eternal fence-sitters—creatures who refused to commit.

- Heaven’s Boundaries and Hell’s Depth: These boundaries represent absolute moral clarity. There is no room in the cosmos for those who choose moral inaction. By being rejected by both realms, these souls symbolize ultimate futility.

- “Nor praise nor blame”: These words are symbolic of lives that left no impact—neither virtuous nor wicked. In Dante’s cosmology, such a life is worse than one filled with sin and repentance—it is a wasted existence.

Tone & Mood:

- Tone: Virgil’s tone here is cold and contemptuous. There’s a certain disdain in the way he explains the fate of these souls—as if their lack of conviction renders them beneath attention.

- Mood: The mood is bleak and pitiful. Unlike the later torments of the damned, which might inspire horror or awe, this evokes scornful sorrow. The sense of meaninglessness and rejection is chilling.

This passage delivers one of Inferno‘s most memorable and damning judgments: that a soul which lives only for itself—avoiding struggle, responsibility, and moral courage—is not worthy even of damnation. It must linger in an eternal no-man’s-land, forgotten by Heaven and scorned by Hell.

Analysis and Interpretation of Inferno: Canto 3 — Stanza 5

I then: “Master! what doth aggrieve them thus,

That they lament so loud?” He straight replied:

“That will I tell thee briefly. These of death

No hope may entertain: and their blind life

So meanly passes, that all other lots

They envy. Fame of them the world hath none,

Nor suffers; mercy and justice scorn them both.

Speak not of them, but look, and pass them by.”

Summary & Meaning:

Dante, deeply affected by the miserable wailing of these souls, asks Virgil what causes them such sorrow. Virgil answers with sharp clarity: these souls are denied even the hope of death. They exist in a state of perpetual non-being—neither truly alive nor fully dead. Their lives were so empty and meaningless that even the damned have a better fate. These souls are so insignificant that the world doesn’t remember them; their names are erased from history. Mercy will not save them, and justice does not judge them—they are beneath both. Virgil urges Dante not to speak of them, but merely to look—and pass on.

Themes Introduced:

- Oblivion as Punishment: These souls aren’t tortured in the traditional sense but are punished by being forgotten. Dante elevates this to the level of spiritual horror: to be forgotten by history, Heaven, and even Hell is the ultimate insignificance.

- Moral Accountability: Dante makes it clear that not taking a moral stance is, in itself, a grave moral failure. Neutrality is shown to be worse than rebellion or sin because it lacks courage, passion, and substance.

- Eternal Futility: The souls’ endless, meaningless existence speaks to Dante’s theme of divine order: if a life is not lived with purpose—whether good or evil—it is reduced to mere noise, unworthy of divine attention.

Symbolism:

- “Blind life”: Symbolizes spiritual blindness—living without direction, insight, or responsibility. These are people who refused to “see” and confront the moral demands of life.

- “No hope of death”: Represents the denial of release or finality. Death is sometimes seen as a mercy in Hell, but even this is denied to the neutral souls. Their punishment is endless stagnation.

- “Speak not of them”: Virgil’s instruction signifies how truly pathetic these souls are—they don’t deserve the dignity of storytelling or memory. In Dante’s world, even the condemned have a voice. These souls do not.

Tone & Mood:

- Tone: Virgil’s tone is dismissive and disdainful. He shows no pity for these souls, suggesting they are not even worth condemnation—only contempt.

- Mood: The mood here is haunting and sorrowful, but also slightly chilling. There’s a sharp contrast between the emotional noise of the souls and the absolute silence Virgil demands from Dante about them.

This passage crystalizes one of the Inferno’s darkest truths:

To have lived without making a mark—for good or ill—is to forfeit one’s place in eternity.

These souls did not sin greatly, but they also did nothing at all. They chose the comfort of inaction over the struggle of virtue or even the passion of vice—and for that, they earn not torment, but oblivion.

Analysis and Interpretation of Inferno: Canto 3 — Stanza 6

And I, who straightway look’d, beheld a flag,

Which whirling ran around so rapidly,

That it no pause obtain’d: and following came

Such a long train of spirits, I should ne’er

Have thought, that death so many had despoil’d.

Summary & Meaning:

Dante looks where Virgil directs and sees a flag—constantly spinning, never stopping—and behind it, an endless train of souls chasing it. The crowd is so large it shocks Dante; he is stunned that death has taken so many people. These are the morally indifferent souls described earlier—those who lived without committing to good or evil. They are doomed to chase a meaningless banner forever, symbolizing the purposelessness of their lives.

Themes Explored:

- The Futility of a Life Without Purpose: These souls now chase a flag they can never catch—just as they spent their lives chasing nothing of value, or constantly shifting desires and allegiances.

- Restlessness of the Spirit: There is no peace or stillness for these souls. Just as they never settled on a moral path in life, they are denied peace in the afterlife.

- Sheer Scale of Indifference: Dante is amazed by how many are condemned to this fate, suggesting that moral apathy is more common—and more dangerous—than outright evil.

Symbolism:

- The Whirling Flag: This is a powerful metaphor. The flag, constantly moving, stands for the ever-changing motivations of the indecisive. It has no emblem, no meaning—it just moves, and they follow. It mocks the notion of loyalty, direction, or cause.

- Endless Procession: The never-ending line of souls is symbolic of the countless people in the world who live without conviction, showing that Hell is not just for the spectacularly wicked, but also for the spiritually empty.

- No Pause: Their chase never ends—no rest, no reflection, no destination. Their fate is to eternally repeat their indecisiveness.

Tone & Mood:

- Tone: Dante’s tone is one of awe and disbelief. It shifts slightly from horror to stunned recognition—he is learning that Hell isn’t just about grand evils, but common, quiet failures.

- Mood: The mood is chaotic and hopeless. The frenzied motion of the flag and the relentless, aimless pursuit create a sense of madness and despair.

This image of the whirling flag and the aimless multitude is one of Dante’s most damning allegories. These souls didn’t stand for anything, so now they chase nothing.

Analysis and Interpretation of Inferno: Canto 3 — Stanza 7

When some of these I recogniz’d, I saw

And knew the shade of him, who to base fear

Yielding, abjur’d his high estate. Forthwith

I understood for certain this the tribe

Of those ill spirits both to God displeasing

And to his foes. These wretches, who ne’er lived,

Went on in nakedness, and sorely stung

By wasps and hornets, which bedew’d their cheeks

With blood, that mix’d with tears dropp’d to their feet,

And by disgustful worms was gather’d there.

Summary & Meaning:

As Dante watches the crowd chasing the whirling flag, he recognizes one soul in particular—someone who once held a high position but gave it up out of cowardice. This solidifies Dante’s realization: these are the souls who were neither for God nor against Him, rejected by both Heaven and Hell.

Their punishment is brutal. They are naked, exposed, and constantly stung by wasps and hornets. The blood and tears they shed from these stings fall to the ground, where disgusting worms feed on the mixture. It’s a deeply unsettling, degrading scene.

Themes Deepened:

- Cowardice and the Fall from Grace: Dante highlights that not all sin is action—inaction can be just as damnable. The specific soul he recognizes is widely interpreted to be Pope Celestine V, who abdicated the papacy and, in Dante’s view, opened the door for corruption (though Dante never names him outright).

- Suffering as Self-inflicted: These souls are stung by wasps—like a physical manifestation of their inner cowardice. Their own choices torment them now, and even their tears become part of the grotesque ecosystem of Hell.

- Disgrace Through Exposure: Their nakedness strips them of all dignity. They have no covering, no protection, just as they had no moral armor in life. Their vulnerability is absolute.

Symbolism:

- The Recognized Shade: Often thought to be Celestine V, he symbolizes the tragic consequences of moral evasion, even by someone in high office. His “base fear” caused real-world suffering, and Dante views that fear as betrayal of divine responsibility.

- Wasps and Hornets: Represent the inner torment that arises from a guilty conscience and the sting of regret. They inflict pain continuously, driving the soul forward in agony.

- Blood and Tears Feeding Worms: A grotesque image of moral decay, where even the suffering of the soul becomes fuel for corruption. The worms, symbols of filth and death, feast on what’s left of the person’s dignity.

Tone & Mood:

- Tone: Dante’s tone is sharper now—he’s not just observing with horror; he’s passing judgment. His disgust for these souls is evident. This is not pity—it’s moral contempt.

- Mood: The mood becomes increasingly grotesque and pitiful, almost nauseating. The imagery is meant to disturb, and it does—because it reflects a complete spiritual collapse.

This is one of Dante’s harshest moral statements:

To refuse to stand for anything is not to avoid judgment—but to forfeit even the possibility of redemption.

These souls didn’t choose evil—but they chose nothing, and in Dante’s moral universe, that is the most pitiful sin of all.

Analysis and Interpretation of Inferno: Canto 3 — Stanza 8

Then looking farther onwards I beheld

A throng upon the shore of a great stream:

Whereat I thus: “Sir! grant me now to know

Whom here we view, and whence impell’d they seem

So eager to pass o’er, as I discern

Through the blear light?” He thus to me in few:

“This shalt thou know, soon as our steps arrive

Beside the woeful tide of Acheron.”

Summary & Meaning:

As Dante continues his descent, he sees a crowd gathering along the shore of a vast, dark river. The people appear restless, urgent, desperate to cross. Dante, confused and curious, asks Virgil who they are and why they’re so eager. Virgil answers only briefly, promising that once they reach the river Acheron, all will be revealed.

Themes Introduced or Reinforced:

- The Journey into the Unknown: The crowd’s eagerness to cross—despite heading into eternal torment—evokes a mysterious pull of divine justice. These souls are compelled not by external force but by an inner drive, which is a common theme in Inferno: every soul in Hell is there by its own accord.

- Anticipation of Judgment: The image of the dead queuing at the riverbank suggests finality and the transition to fate. It echoes ancient beliefs (especially Greek mythology) about the soul’s journey after death.

- Spiritual Geography: Dante’s Hell is not just psychological or metaphorical—it’s mapped, structured, and progressive. Each level has a threshold, and Acheron is the first major boundary.

Symbolism:

- The River Acheron: A direct reference to Greek mythology, Acheron is one of the rivers of the underworld. In Dante’s universe, it becomes the boundary line between the outer vestibule (the neutral souls) and the beginning of true damnation in Hell proper. It marks the moment where the soul accepts its punishment.

- The Bleared Light: Dante uses light imagery here to suggest a fading sense of reality. As they approach deeper into Hell, the clarity of the world diminishes—shadows grow, and the lines between perception and horror blur.

- The Restless Throng: These souls, despite knowing they’re heading toward punishment, are eager to cross. Their desire is no longer governed by free will but by divine judgment—they are drawn to the place that matches their inner truth.

Tone & Mood:

- Tone: The tone is curious but cautious. Dante is trying to understand the process and significance of the next stage, and Virgil is measured in his guidance—offering just enough to keep Dante (and the reader) intrigued.

- Mood: The mood here is ominous and suspenseful. There’s a sense of momentum, as though something irreversible is about to happen. The hush before the plunge.

This passage is the threshold moment, where Dante prepares to leave behind not just the neutral souls but the very idea of limbo. What lies ahead is true Hell, and the first ferryman—Charon—waits just beyond the mist.

Analysis and Interpretation of Inferno: Canto 3 — Stanza 9

Then with eyes downward cast and fill’d with shame,

Fearing my words offensive to his ear,

Till we had reach’d the river, I from speech

Abstain’d. And lo! toward us in a bark

Comes on an old man hoary white with eld,Crying, “Woe to you wicked spirits! hope not

Ever to see the sky again. I come

To take you to the other shore across,

Into eternal darkness, there to dwell

In fierce heat and in ice. And thou, who there

Standest, live spirit! get thee hence, and leave

These who are dead.” But soon as he beheld

I left them not, “By other way,” said he,

“By other haven shalt thou come to shore,

Not by this passage; thee a nimbler boat

Must carry.” Then to him thus spake my guide:

“Charon! thyself torment not: so ’t is will’d,

Where will and power are one: ask thou no more.”

Summary & Meaning:

As Dante, filled with shame and silence, reaches the river Acheron with Virgil, an ancient ferryman named Charon approaches in a bark (boat). Charon curses the damned souls and warns them they will never see the heavens again. He prepares to ferry them to their eternal punishment across the river.

When he notices Dante is still alive, Charon refuses him passage, saying he must go by a different route. But Virgil intervenes with divine authority, telling Charon that this journey is willed from above, and thus Dante must pass.

This scene dramatizes the threshold into actual Hell, and Dante’s status as a living soul among the dead is made stark.

Themes Introduced or Reinforced:

- Divine Authority vs Infernal Will: Charon objects to Dante’s presence—but Virgil reminds him that in Hell, divine will is law. This reinforces the theme that all things in the Divine Comedy operate under a higher justice, even the chaotic ones.

- Rejection of the Living in the Realm of the Dead: Dante being alive makes him an anomaly in Hell. Charon’s protest underscores the unnaturalness of his journey—and also raises tension around whether he can safely make it through.

- The Soul’s Fate After Death: Charon’s fierce declaration reveals the stark finality awaiting the damned: eternal darkness, suffering in fire and ice, and no hope of redemption.

Symbolism:

- Charon: Taken directly from Greek mythology, Charon ferries souls across the river to the underworld. In Dante’s version, he represents the reluctant but bound servant of divine justice. His unwillingness to carry Dante adds drama, but his eventual compliance shows that even infernal figures must obey divine decree.

- The Bark (Boat): Symbolizes the crossing from the world of the living (or its borderlands) into the realm of punishment and judgment. It’s like stepping into the eternal consequence of one’s earthly life.

- Fire and Ice: Charon’s warning about both heat and cold prefigures the types of punishments in Hell—this isn’t just a fiery inferno, but a place of contrasting torments tailored to sin.

- Eyes Cast Down in Shame: Dante’s body language shows humility and dread. He senses the gravity of the journey and fears having offended Virgil—representing moral awakening and self-awareness.

Tone & Mood:

- Tone: The tone is grave, mythic, and commanding. Charon’s arrival marks a shift into truly epic terrain, with booming declarations and mythological power.

- Mood: The mood is foreboding and surreal. There’s awe, terror, and a heavy sense of crossing a point of no return. This is a turning point: once they cross Acheron, Dante steps fully into the Inferno proper.

This section beautifully blends classical mythology with Christian allegory, something Dante does masterfully throughout The Divine Comedy. Charon is not just a mythic figure—he’s now an agent of divine justice, reluctantly ferrying the damned because Heaven says so.

Analysis and Interpretation of Inferno: Canto 3 — Stanza 10

Straightway in silence fell the shaggy cheeks

Of him the boatman o’er the livid lake,

Around whose eyes glar’d wheeling flames. Meanwhile

Those spirits, faint and naked, color chang’d,

And gnash’d their teeth, soon as the cruel words

They heard. God and their parents they blasphem’d,

The human kind, the place, the time, and seed

That did engender them and give them birth.

Summary & Meaning:

As Dante, filled with shame and silence, reaches the river Acheron with Virgil, an ancient ferryman named Charon approaches in a bark (boat). Charon curses the damned souls and warns them they will never see the heavens again. He prepares to ferry them to their eternal punishment across the river.

When he notices Dante is still alive, Charon refuses him passage, saying he must go by a different route. But Virgil intervenes with divine authority, telling Charon that this journey is willed from above, and thus Dante must pass.

This scene dramatizes the threshold into actual Hell, and Dante’s status as a living soul among the dead is made stark.

Themes Introduced or Reinforced:

- Divine Authority vs Infernal Will: Charon objects to Dante’s presence—but Virgil reminds him that in Hell, divine will is law. This reinforces the theme that all things in the Divine Comedy operate under a higher justice, even the chaotic ones.

- Rejection of the Living in the Realm of the Dead: Dante being alive makes him an anomaly in Hell. Charon’s protest underscores the unnaturalness of his journey—and also raises tension around whether he can safely make it through.

- The Soul’s Fate After Death: Charon’s fierce declaration reveals the stark finality awaiting the damned: eternal darkness, suffering in fire and ice, and no hope of redemption.

Symbolism:

- Charon: Taken directly from Greek mythology, Charon ferries souls across the river to the underworld. In Dante’s version, he represents the reluctant but bound servant of divine justice. His unwillingness to carry Dante adds drama, but his eventual compliance shows that even infernal figures must obey divine decree.

- The Bark (Boat): Symbolizes the crossing from the world of the living (or its borderlands) into the realm of punishment and judgment. It’s like stepping into the eternal consequence of one’s earthly life.

- Fire and Ice: Charon’s warning about both heat and cold prefigures the types of punishments in Hell—this isn’t just a fiery inferno, but a place of contrasting torments tailored to sin.

- Eyes Cast Down in Shame: Dante’s body language shows humility and dread. He senses the gravity of the journey and fears having offended Virgil—representing moral awakening and self-awareness.

Tone & Mood:

- Tone: The tone is grave, mythic, and commanding. Charon’s arrival marks a shift into truly epic terrain, with booming declarations and mythological power.

- Mood: The mood is foreboding and surreal. There’s awe, terror, and a heavy sense of crossing a point of no return. This is a turning point: once they cross Acheron, Dante steps fully into the Inferno proper.

This section beautifully blends classical mythology with Christian allegory, something Dante does masterfully throughout The Divine Comedy. Charon is not just a mythic figure—he’s now an agent of divine justice, reluctantly ferrying the damned because Heaven says so.

Analysis and Interpretation of Inferno: Canto 3 — Stanza 11

Then all together sorely wailing drew

To the curs’d strand, that every man must pass

Who fears not God. Charon, demoniac form,

With eyes of burning coal, collects them all,

Beck’ning, and each, that lingers, with his oar

Strikes. As fall off the light autumnal leaves,

One still another following, till the bough

Strews all its honours on the earth beneath;E’en in like manner Adam’s evil brood

Cast themselves one by one down from the shore,

Each at a beck, as falcon at his call.

Summary & Meaning:

As Dante watches, the damned souls—wailing and miserable—gather at the cursed shore of the river Acheron. These are the souls of those who lived without reverence for God. Charon, now described as a demonic figure with burning eyes, herds the souls toward the boat. Those who hesitate are struck with his oar.

The souls cast themselves down into the boat like falling autumn leaves—a haunting image of mass surrender to their fate. Dante compares their response to trained falcons answering their master’s call, emphasizing how inevitable and inescapable their damnation is.

Themes Introduced or Reinforced:

- Inevitability of Divine Judgment: No one escapes this passage—“every man must pass / Who fears not God”. It’s not just punishment—it’s cosmic order at work.

- Loss of Individuality: The damned no longer act with free will. They fall into Hell like leaves, or answer like falcons to a master. The soul’s agency is gone—replaced by mechanical obedience to judgment.

- Damnation as Natural Process: The comparison to autumn leaves falling from a tree suggests that entering Hell is as natural and unstoppable as the seasons. Sin has a consequence that is organic and inevitable.

Symbolism:

- Burning Eyes of Charon: Symbolic of demonic fury and the torment awaiting the damned. His eyes are like coals—reflecting the fiery punishments to come.

- Striking with the Oar: The oar becomes a tool of coercion, not just transportation. It shows that Hell is not entered willingly by all, but none can resist it.

- Autumn Leaves: This is one of Dante’s most famous and haunting metaphors. Leaves fall when they are detached from life—like these souls, who have lost their connection to divine grace.

- Falcons at the Call: A falcon answering its master’s whistle suggests trained obedience. These souls, once rebellious in life, now follow orders without resistance, further highlighting the loss of moral and spiritual freedom.

Tone & Mood:

- Tone: The tone here is resigned and mournful, but also intensely visual and mythic. Dante’s narrative style elevates the scene with poetic sorrow.

- Mood: The mood is tragic and eerily calm, like the quiet of falling leaves—but beneath it lies agony and submission. There’s an undercurrent of dread, made worse by how natural everything feels.

This section marks the final transition before Dante is truly within the First Circle of Hell (Limbo). His journey has already passed the warning at the Gate and entered into the space of moral consequence—a place where divine justice moves with unrelenting grace and force.

Analysis and Interpretation of Inferno: Canto 3 — Stanza 11

Thus go they over through the umber’d wave,

And ever they on the opposing bank

Be landed, on this side another throng

Still gathers. “Son,” thus spake the courteous guide,

“Those, who die subject to the wrath of God,

All here together come from every clime,

And to o’erpass the river are not loth:

For so heaven’s justice goads them on, that fear

Is turn’d into desire. Hence ne’er hath past

Good spirit. If of thee Charon complain,

Now mayst thou know the import of his words.”

Summary & Meaning:

As Dante observes, souls are continuously ferried across the dark river Acheron by Charon. The boat drops them on the opposite bank, but more souls instantly gather, forming an endless cycle of damnation. Virgil explains that these are the souls of those who died in God’s wrath—sinners from every land, drawn here not by external force but by a twisted inner compulsion.

Despite the horror that awaits, they come willingly, because divine justice drives them with such intensity that their fear transforms into desire—not desire for punishment, but for the fulfillment of their fated judgment. Virgil also clarifies why Charon had protested Dante’s presence earlier: no righteous soul has ever passed through this gate.

Themes Introduced or Reinforced:

- Divine Justice as Compelling Force: Heaven’s justice doesn’t just punish—it compels sinners to enter Hell of their own accord, driven by an irresistible spiritual force.

- Desire for Judgment: A paradox is introduced here: the souls desire punishment, because divine order demands it. This desire is not rational—it’s existential, like gravity pulling them downward.

- Eternal Process of Damnation: There is no pause or break in this system. As one group lands, another gathers. This illustrates the timeless, ceaseless nature of Hell’s operations.

- Exclusivity of the Infernal Path: No good soul ever passes this way. This isn’t a place of trial—it’s final judgment. It emphasizes the separation of the damned from the saved.

Symbolism:

- “Umber’d Wave”: The dark river Acheron, shaded and murky, symbolizes spiritual ignorance, despair, and transition from life to damnation.

- The Boat’s Endless Cycle: Represents the unending arrival of sinners into Hell. Like a spiritual conveyor belt, the process is both mechanical and grimly efficient.

- Desire to Cross the River: Symbolic of how souls, even in the afterlife, are subject to divine will. Their inner compasses have shifted—they now seek what they once feared, drawn to it by truth too overwhelming to resist.

Tone & Mood:

- Tone: Calm but weighty and philosophical. Virgil speaks with authority and compassion, guiding Dante through existential revelation.

- Mood: Inevitable and eerie. The souls are not being dragged—they are rushing into Hell willingly, which creates a chilling sense of order within horror. There’s a somber beauty in how divine justice aligns even terror with desire.

This moment is important because it reveals a profound metaphysical truth in Dante’s theology: Hell is not unjust. It is the necessary end for those who have aligned themselves against divine will—so much so that even the souls accept their damnation as just.

Analysis and Interpretation of Inferno: Canto 3 — Stanza 12

This said, the gloomy region trembling shook

So terribly, that yet with clammy dews

Fear chills my brow. The sad earth gave a blast,

That, lightening, shot forth a vermilion flame,

Which all my senses conquer’d quite, and I

Down dropp’d, as one with sudden slumber seiz’d.

Summary & Meaning:

After Virgil’s explanation, the ground itself seems to react to the divine justice in motion. The region trembles violently, and the air is filled with a terrifying blast. A flame of vermilion strikes, resembling lightning, overwhelming Dante’s senses. The overwhelming fear and intensity of the moment cause Dante to faint, as if struck by an overpowering slumber. The scene builds to a dramatic climax, signaling a powerful shift in Dante’s experience in Hell.

Themes Introduced or Reinforced:

- The Power of Divine Justice: The very earth trembles in response to the weight of God’s judgment. This underscores that the entire universe is aligned with divine justice—nothing is neutral. Even nature itself reacts with awe and fear.

- Overwhelming Fear and Powerlessness: Dante is struck with such fear and awe that he loses control of his senses. This highlights the powerlessness of mortal man in the face of divine will.

- Supernatural and Terrifying Forces: The flame and the sudden trembling of the earth reflect supernatural forces at work, signifying that Hell is not just a physical place but a realm ruled by spiritual and existential forces that transcend human understanding.

Symbolism:

- Trembling Region: The earth shaking indicates the very foundations of existence are being stirred by the presence of divine justice. It’s a cosmic disturbance, revealing that judgment is not just a personal or human event but a universal upheaval.

- Vermilion Flame: This red flame, often associated with violence and punishment, symbolizes both the fury of divine wrath and the purifying fire of judgment that overwhelms the sinner.

- Fainting/Slumber: Dante’s fainting mirrors the sudden shock of realizing the full scope of divine retribution. It’s a symbol of human fragility in the face of overwhelming spiritual truths.

Tone & Mood:

- Tone: The tone is ominous and intense. The passage’s language creates a sense of dread and unrelenting fear. Virgil’s calm explanation is sharply contrasted by the terrifying forces that overwhelm Dante.

- Mood: The mood is one of overwhelming terror and awe. Dante’s physical collapse emphasizes the all-consuming nature of the experience. There’s an eerie, supernatural quality to the moment, as if the very world is reacting to the presence of divine justice.

This passage really highlights Dante’s vulnerability in the face of Hell’s forces. It serves as a stark reminder of how insignificant and fragile mortal beings are when exposed to divine judgment. Dante’s experience is both humbling and terrifying, and it’s a pivotal moment in the journey where the reality of the Inferno fully sinks in.

YouTube Channel Link:

YouTube Channel Link:

YouTube Channel Link:

YouTube Channel Link