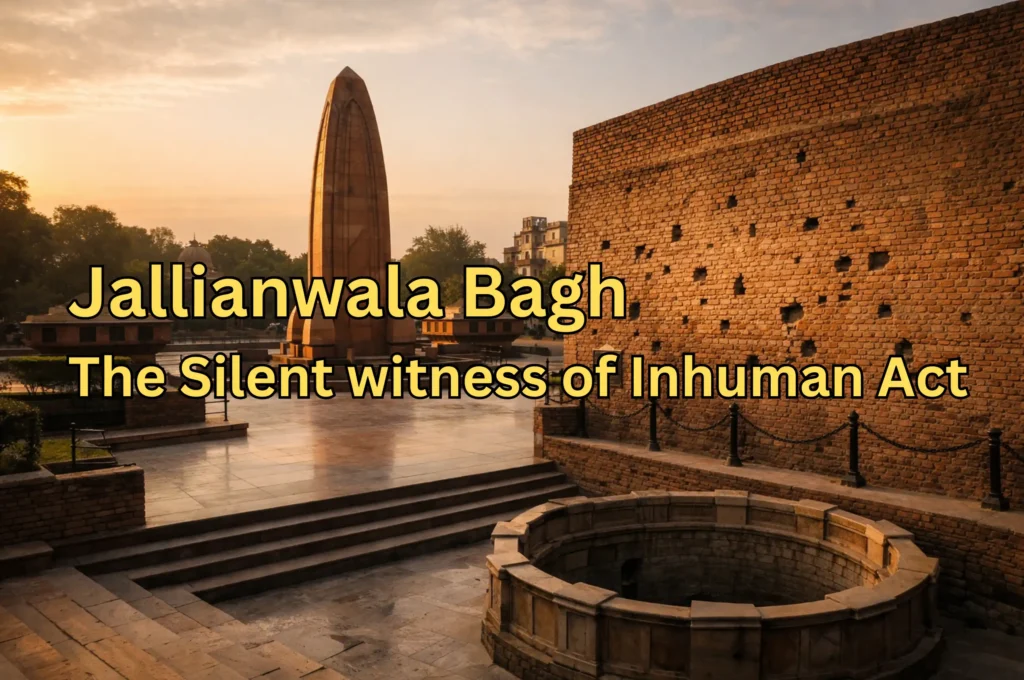

Some events in history are not remembered because of their dates, but because of the pain they left behind. The Amritsar Massacre, better known as the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, is one such tragedy—an event so brutal that it shattered any remaining illusion of British justice in India.

On April 13, 1919, in Amritsar, Punjab, hundreds of unarmed Indian men, women, and children were mercilessly gunned down by British Indian Army troops under the command of Brigadier General Reginald Dyer. What unfolded that evening was not an act of crowd control—it was a calculated display of colonial terror.

Even today, more than a century later, Jallianwala Bagh remains a silent witness to one of the most inhuman acts in world history.

Also Read: Story of Bhagat Singh | The Pioneer of Indian Freedom Struggle

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

Jallianwala Bagh Events in Detail

A Peaceful Gathering on Baisakhi

The afternoon of April 13, 1919, began like any other festival day in Punjab. Baisakhi, a time of harvest and celebration, had drawn people from nearby villages into Amritsar. Farmers in simple attire, families with children, elderly men leaning on walking sticks—everyone moved through the streets with the ease and familiarity of a day meant for joy.

Jallianwala Bagh, a walled public garden near the Golden Temple, slowly filled with people. Some came intentionally, others wandered in after visiting the city or offering prayers. The mood was calm. Groups sat on the ground talking, children played close to their parents, and a sense of togetherness hung in the air. No banners were raised. No slogans were shouted. It did not feel like a protest ground—it felt like a public meeting on a festive day.

Yet beneath this calm was a quiet sense of concern.

Just days earlier, the British authorities had arrested and deported Dr. Satya Pal and Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew, two deeply respected leaders in Punjab. Their removal had happened without trial, without explanation, and without warning. People were confused, angry, and hurt. Many felt that if such leaders could be taken away so easily, no ordinary citizen was safe.

The gathering at Jallianwala Bagh was meant to address this injustice—but peacefully. There were to be speeches, discussion, and silent resistance. The people came not to fight, but to be heard.

Most important of all, no one carried weapons. There were no sticks, no stones, no signs of violence. Men, women, children, and the elderly stood or sat together, believing that their presence alone was enough. They trusted that a peaceful assembly, on a religious and cultural festival, would not be met with force.

What they did not know was that Jallianwala Bagh was a closed space—surrounded by walls, with narrow exits. What seemed like a safe gathering place would soon become a cage.

At that moment, as laughter mixed with conversation and the dust of the ground settled under thousands of feet, no one could imagine that within minutes this peaceful scene would collapse into terror, bloodshed, and silence.

The people had come to celebrate life.

History was about to confront them with death.

Arrival of General Dyer

As the peaceful gathering continued inside Jallianwala Bagh, around 5:00 PM, a sudden and ominous shift took place outside its walls. Brigadier General Reginald Dyer arrived at the site, accompanied by a contingent of British Indian Army soldiers, all armed and in formation.

Jallianwala Bagh was not an open field. It was a confined enclosure, surrounded on all sides by high brick walls. The few exits it had were narrow lanes, some partially blocked, others already crowded with people moving in and out. Anyone familiar with the place knew one thing clearly—once inside, escape was difficult.

Dyer surveyed the crowd from the entrance. He did not walk in to address the people.

He did not ask them to disperse.

He did not issue a warning.

There was no announcement, no declaration of curfew, no attempt at dialogue.

Instead, Dyer positioned his troops at the main entrance, deliberately blocking one of the primary exits. The soldiers stood in a line, rifles aimed forward, facing thousands of unarmed civilians trapped inside the enclosure.

Then, without hesitation, Dyer gave the order to fire.

There was:

- No provocation

- No violence from the crowd

- No attempt at crowd control

This was not a response to disorder.

This was a deliberate, calculated use of lethal force.

Ten Minutes of Uninterrupted Gunfire

The first shots rang out without warning—and within seconds, panic swept through the garden.

Armed with rifles and machine guns, the soldiers fired directly into the densest parts of the crowd, where people were packed tightly together. The gunfire did not pause. It did not slow. It continued relentlessly for nearly ten full minutes.

What followed was chaos beyond words.

People ran in every direction, desperately searching for an exit that no longer existed. Some pressed themselves against the walls, hoping to make themselves invisible. Others stumbled and fell, only to be trampled by those running behind them.

Children were knocked down in the rush.

Parents lost sight of their families within moments.

Cries for help were drowned out by the sound of gunfire.

Bodies began to pile up—one falling over another—turning the ground into an obstacle course of the wounded and the dead. The confined space offered no shelter, no cover, no escape.

The firing did not stop because mercy prevailed.

It stopped only because the soldiers ran out of ammunition.

When the guns finally fell silent, Jallianwala Bagh was no longer a gathering place.

It had become a field of devastation, filled with lifeless bodies, injured survivors, and a silence heavy with shock and grief.

In those ten minutes, the illusion of British justice was destroyed forever—and the course of India’s freedom struggle was changed beyond repair.

Casualties: Numbers That Could Never Tell the Full Story

According to official British records, 379 people were killed in the massacre. However, independent investigations and Indian sources suggest the real number was far higher—possibly close to 1,000 deaths.

More than 1,000 people were injured, many of them severely. Hospitals were overwhelmed, and for hours after the firing, wounded people lay unattended, bleeding in the open.

These were not militants or fighters.

They were festival-goers, protesters, and families.

The Shahidi Kuan: The Well of Martyrs

As bullets rained down and exits remained blocked, many people saw no way out.

Inside the Jallianwala Bagh compound was a deep well. In sheer panic, dozens of people jumped into it, hoping to escape the gunfire. Many died instantly from the fall; others suffocated or were crushed as more bodies fell in.

This well later came to be known as Shahidi Kuan, meaning “The Well of Martyrs.”

It stands today as one of the most haunting symbols of the massacre—proof of the desperation and terror faced by the crowd.

Dyer’s Justification and Global Condemnation

After the massacre, General Dyer expressed little to no regret. He openly defended his actions, stating that his objective was to:

- Assert British authority

- Create fear among Indians

- Prevent future uprisings

Rather than seeing the killings as excessive, he described them as necessary.

This attitude shocked many across the world. The incident was widely condemned in India and criticized internationally. Newspapers, political leaders, and human rights voices questioned how such an act could be carried out against unarmed civilians.

Impact on India’s Freedom Movement

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre sent a wave of anger and grief across India. Public trust in British rule collapsed almost completely. Protests, strikes, and demonstrations spread rapidly.

For Mahatma Gandhi, the massacre marked a decisive moment. He intensified his call for:

- Nonviolent resistance

- Civil disobedience

- Complete rejection of British moral authority

From this point onward, the Indian independence movement gained a new urgency and mass participation.

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre – The Aftermath

Britain Forced to Respond: The Hunter Commission

The scale of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre was so shocking that even the British government could not fully ignore it. Facing mounting criticism from India and growing discomfort abroad, the British authorities announced an official inquiry.

In 1920, the government constituted the Hunter Commission to investigate what had happened in Amritsar.

After examining testimonies and evidence, the commission:

- Strongly condemned General Dyer’s actions

- Declared the use of force excessive and unjustified

- Recommended that Dyer be removed from military service

As a result, Reginald Dyer was dismissed from his post and formally censured.

However, what followed exposed the deep moral divide between colonial power and colonial victims.

No Trial, No Punishment — Only Silence

Despite the commission’s findings, General Dyer was never tried in a criminal court.

No jail sentence.

No legal accountability.

For the families of the victims, justice remained painfully incomplete.

Even more disturbing was the reaction in Britain. Sections of British society:

- Defended Dyer’s actions

- Collected public donations in his honor

- Presented him with a ceremonial sword

To many Indians, this felt like a second betrayal—proof that Indian lives were valued far less than imperial authority.

General Reginald Dyer: A Life Without Legal Consequences

It is important to clarify a common misconception:

General Dyer was not assassinated.

After his dismissal, Dyer:

- Retired from service in 1920

- Lived quietly in the United Kingdom

- Died a natural death in 1927

Though widely condemned in India and criticized internationally, he never faced legal punishment for ordering the massacre.

History, however, judged him far more harshly than any court ever did. Today, his name is remembered not as that of a soldier, but as a symbol of colonial cruelty and unchecked power.

Sardar Udham Singh: Revenge Born of Memory

While the law failed the victims, memory did not.

One man carried the trauma of Jallianwala Bagh for over two decades—Sardar Udham Singh.

He believed that the massacre was not only the responsibility of General Dyer, but also of the colonial administrators who approved, defended, and justified the killings. Chief among them was Sir Michael O’Dwyer, the former Lieutenant Governor of Punjab.

The Assassination of Michael O’Dwyer

On March 13, 1940, Udham Singh entered Caxton Hall, London, where a meeting was being held by the East India Association and the Royal Central Asian Society.

Sir Michael O’Dwyer was present as a guest speaker.

As O’Dwyer was leaving the hall, Udham Singh fired multiple bullets, killing him on the spot.

Udham Singh made no attempt to escape. He was arrested immediately.

“I Did It for My People”

During his trial, Udham Singh made his motive clear.

He stated that the assassination was revenge for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

He was convicted and sentenced to death.

On July 31, 1940, Udham Singh was executed at Pentonville Prison in London.

In India, he was remembered not as a murderer, but as a martyr—a man who gave voice to those who had been silenced by bullets.

Conclusion: An Inhuman Act the World Must Remember

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre remains one of the most inhuman acts in modern history.

It exposed a painful contradiction:

- Nations that speak today of human rights and equality

- Once ruled through fear, violence, and racial superiority

This was the cost India paid under imperialism:

- Children shot

- Elderly killed

- No warning

- No escape

Reading this story makes one feel the true price of freedom.

The massacre also deeply impacted young minds—most notably Bhagat Singh, who was still a child at the time. Witnessing such brutality convinced him that peaceful appeals alone could not end injustice. For him, Jallianwala Bagh marked the end of innocence.

Imagine the scene:

- A walled garden

- Narrow exits blocked

- Bullets fired into a helpless crowd

Any act that treats human lives with such cruelty deserves to be remembered—not to spread hatred, but to ensure history never repeats itself.

This is not just a story.

This is real history.

And if you ever visit Jallianwala Bagh, you won’t need words.

The silence itself will leave you with goosebumps and grief.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

What was the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre?

The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre was a brutal incident that occurred on April 13, 1919, in Amritsar, Punjab, when British Indian Army soldiers opened fire on a peaceful, unarmed gathering of Indian civilians. Hundreds were killed and thousands injured, making it one of the most tragic events in Indian history.

Why had people gathered at Jallianwala Bagh on that day?

People had gathered for two reasons:

To celebrate Baisakhi, an important Punjabi harvest festival

To peacefully protest the arrest and deportation of Indian leaders Dr. Satya Pal and Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew

There was no plan for violence or rebellion.

Was the crowd armed or violent?

No. The crowd was completely unarmed.

It included:

Men and women

Children and elderly people

Farmers, traders, and families

There was no provocation, no attack, and no threat from the public.

Who ordered the firing at Jallianwala Bagh?

The firing was ordered by Brigadier General Reginald Dyer, a British officer commanding troops in Amritsar at the time.

He gave the order without warning, without negotiation, and without asking the crowd to disperse.

Why was escape almost impossible for the people?

Jallianwala Bagh was a walled enclosure with:

High surrounding walls

Only a few narrow exits, some blocked or congested

When firing began, people were trapped, leaving them with almost no chance to escape.

How long did the firing last?

The firing continued for approximately ten minutes.

It stopped only because the soldiers ran out of ammunition, not because the situation was brought under control.

How many people were killed in the massacre?

Official British figure: 379 deaths

Independent estimates: 700 to over 1,000 deaths

Injured: More than 1,000 people

The exact number was never conclusively established.

What is the Shahidi Kuan (Well of Martyrs)?

The Shahidi Kuan is a well located inside Jallianwala Bagh.

When people could not escape the gunfire, many jumped into the well in desperation. Numerous victims died from drowning, injuries, or being crushed by others.

Today, the well stands as a symbol of sacrifice and desperation.

Did General Dyer show any regret after the massacre?

No. General Dyer showed no remorse.

He later stated that his goal was to:

Instill fear among Indians

Prevent future resistance

Assert British authority

He even claimed he would have continued firing if he had more ammunition.

Was General Dyer punished for the massacre?

General Dyer was:

Dismissed from service

Censured by the British government

However:

He was never tried in a court

He was never imprisoned

He died of natural causes in 1927.

What was the Hunter Commission?

The Hunter Commission (1920) was a British inquiry formed to investigate the massacre.

It:

Condemned Dyer’s actions

Declared the firing excessive and unjustified

Recommended his removal from service

Despite this, no legal punishment followed.

Who was Sir Michael O’Dwyer?

Sir Michael O’Dwyer was the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab at the time of the massacre.

He:

Supported General Dyer’s actions

Publicly justified the massacre

Represented the political authority behind the military action

Why did Sardar Udham Singh kill Michael O’Dwyer?

Sardar Udham Singh assassinated Michael O’Dwyer in London in 1940 as an act of revenge for the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre.

He believed O’Dwyer was morally responsible for approving and defending the killings.

Was General Dyer assassinated by Udham Singh?

No.

This is a common misconception.

Reginald Dyer ordered the firing

Michael O’Dwyer supported and justified it

Udham Singh assassinated Michael O’Dwyer, not Dyer.

How did the massacre affect India’s freedom movement?

The massacre:

Destroyed Indian trust in British justice

Radicalized public opinion

Strengthened mass participation in the freedom struggle

Marked a turning point for Mahatma Gandhi’s civil disobedience movement

It transformed the demand for reform into a demand for complete independence.

Did the massacre influence Bhagat Singh?

Yes.

Bhagat Singh was deeply affected as a child by the massacre.

It shaped his revolutionary thinking and convinced him that injustice could not always be met with silence or compromise.

Why is Jallianwala Bagh still important today?

Jallianwala Bagh is:

A national memorial

A reminder of colonial brutality

A warning against unchecked power

A symbol of the price paid for freedom

The bullet marks and Shahidi Kuan still stand as silent witnesses.

Can Jallianwala Bagh be visited today?

Yes.

Jallianwala Bagh is open to the public in Amritsar and preserved as a memorial. Visitors often describe the experience as deeply emotional and humbling.

Why is the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre called an inhuman act?

Because:

Unarmed civilians were targeted

No warning was given

Escape was blocked

Firing continued deliberately

No accountability followed

It violated the most basic principles of humanity.