When did religion enter Indian society — and why did it take the shape it did?

This question sits at the crossroads of archaeology, anthropology, and history. For a civilization as ancient and continuous as India, religion feels timeless, almost inseparable from social life. Yet when we examine the earliest material evidence — especially from the Indus Valley Civilization — the picture becomes far more complex.

Well-planned cities, advanced sanitation systems, standardized weights, and vibrant trade networks flourished thousands of years ago, but clear signs of organized religion — temples, priestly hierarchies, canonical texts, or dominant gods — remain strikingly absent. This raises a deeper historical puzzle: was religion always central to Indian society, or did it emerge gradually in response to changing social, environmental, and political conditions?

To answer this, we must move beyond myths and assumptions and look closely at evidence — from archaeological remains and burial practices to early ritual traditions and the rise of Vedic literature. Only then can we understand not just when religion entered Indian society, but why it did so at that particular moment in history.

Read More in History Section.

Also read articles on Indian History

Did the Indus Valley Civilization Have Religion?

Table of contents

When Did Religion Enter Indian Society — Gradually or Suddenly?

When did religion enter Indian society as an organized, named, doctrine-bearing system — and did it happen slowly or all at once?

There’s a strange, magnetic pause in the story of South Asia. On one side stand the carefully planned cities of the Indus (Harappa, Mohenjo-daro), where drainage systems, craft specialization, granaries, and markets speak of extraordinary civic energy. On the other echo the thunderous hymns of later Vedic poets, where gods quarrel, kings sacrifice, and priestly ritual organizes social life.

Between these two scenes lies a question that is as simple as it is unsettling. Was religion already present in the streets of the Indus cities, quietly embedded in daily practice? Or did it emerge later, growing from a different historical soil altogether? If religion took shape after the Harappan world faded, what social forces nudged a largely ritual-centered human life toward named gods, priestly hierarchies, and sacrificial systems?

This article follows the evidence — archaeological traces, burial practices, commodities and climate shifts, oral traditions, and early texts. Along the way, we encounter ancient baths that may have functioned as ritual pools, enigmatic seals that suggest symbolic practice without dogma, and poets who reshaped communal identity through liturgy. More than a timeline, this is an attempt to understand why people began to structure meaning in religious forms — and why that shift mattered for the shape of Indian civilization itself.

1. What counts as “religion”? Defining our terms

Before we step into ancient cities and sacred hymns, it helps to pause and ask a simple but important question: what do we actually mean by religion? The word feels familiar, but when applied to deep history, it often carries modern assumptions that don’t always fit the past.

In this article, religion does not simply mean belief. Humans everywhere have believed in unseen forces — fate, ancestors, spirits, or cosmic order. Nor does religion mean ritual alone. Communities can perform rituals for birth, death, seasons, or prosperity without belonging to anything we would recognize as an organized religion.

Here, religion refers to a structured social system, usually marked by several of the following features:

- Named gods or supernatural beings with distinct identities and stories

- Organized rituals overseen by specialists such as priests, rather than practiced informally by everyone

- Shared bodies of religious knowledge, including hymns, doctrines, or ritual rules recognized by a community

- Institutional structures like temples, priesthoods, or ritual calendars tied to authority and public life

- Enduring ideas about morality and the cosmos, such as sin, purity, duty, or the afterlife, that shape social order and power

This definition is deliberately balanced. It is broader than belief — because belief alone leaves little trace in the archaeological record — but narrower than ritual, since rituals can exist without theology, hierarchy, or doctrine.

Why does this distinction matter? Because a society can be deeply symbolic and ritual-rich without having an organized religion in the formal sense. Sacred acts may be woven into daily life without named gods, written traditions, or priestly institutions controlling them.

A simple comparison helps clarify this.

The Indus Valley Civilization shows abundant evidence of ritual and symbolism — public bathing spaces, seals with sacred imagery, and careful treatment of the dead — yet it lacks clear signs of temples, priesthoods, or named deities. By contrast, the later Vedic world presents hymns addressed to specific gods, complex sacrifices conducted by trained priests, and a growing body of ritual knowledge preserved across generations.

Both worlds were meaningful and sacred in different ways. But only one clearly fits the definition of organized religion used here.

Keeping this distinction in mind allows us to ask sharper historical questions: did religion emerge suddenly in India, or did it take shape gradually as ritual practices became structured, specialized, and institutionalized? The rest of this article follows that transformation through evidence, not assumption.

2. The Indus cities: craft, water, and a surprising silence

The mature Indus Civilization (c. 2600–1900 BCE) gave us the earliest urban map of South Asia: wide streets, fired-brick houses, centralized granaries, finely worked beads, seals bearing animals and symbols, and the famous Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro — a public structure that looks, and feels, like ritual architecture.

But when archaeologists look for the signs we usually associate with organized religion — large temples, monumental cult statues, sacrificial altars with repeated deposits, priestly cemeteries, clear iconography of named gods — the results are muted.

What we do find:

- Seals and figurines. Hundreds of seals portray animals, processional scenes and enigmatic animals; some human figures are horned or seated in yogic posture. Terracotta figurines, including mother-goddess-like shapes, appear in houses.

- The Great Bath. A massive tank with steps, drains and waterproofing — it could be a communal bathing tank, or a place for ritual purification.

- Fire altars? Sites such as Kalibangan show traces of hearths and possible fire-altars; whether these were domestic cooking, ritual hearths, or something in between is debated.

- Burials and cremations. The Indus people used varied funerary practices — extended inhumation in some areas, occasional cremation elsewhere — not a single standardized rite across the civilization.

But what’s missing is the kind of institutional complexity we recognize in Egypt or Mesopotamia: monumental state temples with long stratified records of offerings, kings depicted as divine intermediaries, or extensive written ritual prescriptions. The Indus script remains undeciphered, so if such texts existed we cannot read them; yet, the lack of obvious temple complexes or palace-temple compounds suggests a different civic-religious anatomy.

The take-away: The Indus world shows ritual and symbolic life — but not the clear markers of an organized, text-driven religion as seen later.

3. The silence of the script: why undeciphered texts matter

One frustrating but crucial fact about the Indus is the undeciphered script. Short inscriptions exist on seals and potsherds, but they are brief and formulaic. If long ritual manuals or priestly codes were written and copied, they have not survived — or they were not produced in the volume that would leave a clear archaeological signal.

Compare that to the Vedic corpus (composed later): long hymns, ritual prescriptions and layered commentaries that create a textual architecture for religion. Writing — or, more precisely, readable, repeatable textual practice — is a hinge. A literate priesthood that codifies rituals turns fluid cultural practices into a durable religion.

So part of the answer to “when did religion enter?” depends on whether high-volume textuality and priestly authority developed. On current evidence, the Indus leaves us with symbols and repetitive motifs, but no clear, extensive ritual textuality. That suggests the later textual turn — the Vedic composition and its ritual manuals — is a pivotal moment in the institutionalization of religion.

4. The Vedic horizon: hymn, sacrifice, and the rise of priestly knowledge

From roughly 1500 BCE onward, across parts of the northern subcontinent, we find a very different social pattern in the surviving record: the Vedas. These are collections of hymns, ritual formulas and layered liturgies composed, memorized and transmitted by specialist families. Several features matter:

- Named deities. Indra, Agni, Varuna, Soma and others have personalities, myths, and specific roles in the cosmos.

- Sacrificial ritual (yajña). Complex fire rituals, with precise offerings and sequences, require specialist knowledge and trained performers.

- Priestly authority. Brahmin families become custodians of ritual knowledge; ritual competence is a source of status and authority.

- Oral textuality. Even without early writing, these texts were transmitted with strict memorization techniques creating permanence.

This combination — named gods, canonical rituals, and specialist priests — is a clear marker of organized religion by our working definition.

But how did this system grow from earlier practices? Two large processes help explain the shift.

5. Two social engines of religious change

Engine 1 — Social complexity, elites, and legitimation

As societies scale, new forms of social coordination are needed. Urban economies, hierarchical land control, and warrior elites must create social legitimacy that is not purely economic. Ritual — especially large public sacrifice — serves to:

- Display elite authority. Sponsoring a great sacrifice publicly demonstrates wealth, capacity and cosmic favor.

- Create shared symbolism. Hymns and collective rituals fuse disparate communities into single moral imaginations.

- Legitimize new hierarchies. Priesthoods that control ritual knowledge can legitimize kingship and social stratification.

In short, organized religion is an effective technology of rule: it provides narratives, sanctions and public spectacles to justify a new social order. The Vedic sacrificial system fits this function well.

Engine 2 — Mobility, mixing, and new ritual needs

Large climatic and demographic shifts at the end of the third millennium BCE fragmented old systems. If pastoral groups moved into new regions (whether via migration, diffusion or trade), those movements introduced different ritual repertoires, mobility-based cosmologies and emphasis on household sacrifice. The fusion of urban sedentary practices and mobile ritual traditions could produce hybrid forms that crystallize into organized religion.

Where Indus urban centers fell into decline, communities reorganized — landlords, counselors, and war leaders emerged — and ritual became a social adhesive in new, less urban polities.

6. Environmental shocks and the psychology of ritual increase

Another dynamics: crisis breeds ritual. Environmental stress — river shifts, droughts, crop failure — encourages communities to seek control through ritual. Scholars have noted that the drying of the Sarasvati river system and climatic oscillations around 2000–1500 BCE likely affected many communities. Under stress, people often:

- Increase ritual frequency to control what appears uncontrollable.

- Elaborate ritual prescriptions to create predictable social patterns.

- Treat ritual experts as valuable, consolidating their social power.

This “ritual response to crisis” doesn’t create doctrine overnight, but it can magnify ritual practices and give priestly actors social leverage — a stepping-stone to organized religion.

7. The role of literacy, memory, and transmission

Religion becomes durable when the ritual and myth can be transmitted across generations reliably. Two complementary technologies matter:

- Scripted texts (when available) make rituals replicable across space. We have less of this in early South Asia.

- Oral textual traditions — the Vedic memorization techniques — produce similar durability without writing.

The emergence of a ritual class that specializes in exact recitation turns practice into institution. The Vedic corpus is a triumph of oral textuality: it allowed priests to claim ancient authority and control ritual detail tightly.

When religious knowledge becomes a resource (a skill families provide and transmit), it becomes an institution — a key step from ritual practice to religion.

8. Evidence from material culture: temples, iconography, and cult objects

Material correlates of organized religion appear more clearly as we move later in time and geography:

- Stone and brick shrines appear in later periods, sometimes associated with cult images.

- Iconography becomes standardized — gods with attributes, recurring motifs tied to myth.

- Temple economy. As temples amass land and donations, they become bureaucratic and central to religious life.

Compare this to the Indus: small cult objects, seals, and possibly ritual baths, but not the large, persistent temple-economies of early historic South Asia. The archaeological signature thus supports the idea that organized temple-based religion as a major structuring force mainly developed after the Harappan urban phase.

9. Regional diversity and the long tail of religious emergence

One crucial point: religion did not “enter India” in a single moment. Startling regional diversity characterizes the subcontinent’s past. In many places, ritual practices and deities formed locally and later aggregated into broader formations. A few implications:

- Multiple entries. In some regions, organised priestly systems may have fastened earlier; in others, much later.

- Hybridization. The Vedic sacrificial world blended with local cults, animist practices and folk deities, producing the plural religious landscape that followed.

- Continuity and reinvention. Some Indus motifs may have persisted inside folk practice even if institutional religion transformed the upper-caste ritual core.

So, instead of a single “religion arrives” moment, think of a long process: ritual abundance → ritual specialization → textual institutionalization → temple economies.

10. Why this change matters — social, moral, political consequences

The institutionalization of religion carried deep consequences:

- Political integration. Ritual provided a language of legitimacy for rulers and elites across regions.

- Social stratification. Specialization of ritual knowledge often reinforced social hierarchies (later linked to caste formation).

- Cultural memory. Text-based traditions extended the reach of shared narratives, creating broader civilizational identities.

- Moral frameworks. Organized religion offered public ethics and social sanctions that outlived local crises.

All of these changes shaped the next thousand years of South Asian history: the formation of kingdoms, the crystallization of social orders, and the emergence of literary, philosophical traditions.

11. Common objections — careful replies

Objection 1: “The Indus had gods — see the seals.”

Reply: Seals and figures certainly show symbolic and possibly religious behavior, but symbolic practice is not identical to an institutional religion. The seals suggest ritual memory and sacred symbols; they do not prove the existence of a textual priesthood or temple economies.

Objection 2: “Vedic religion was imported; it has nothing to do with Indus traditions.”

Reply: The relationship is complex. Some elements could be new, others may be local continuities reinterpreted. Migration, diffusion and local adaptation all play roles. Archaeology shows both change and continuity.

Objection 3: “Religion can exist without texts.”

Reply: Absolutely — and the Vedic corpus itself was oral for centuries. The important point is institutionalization. Whether by texts, priestly memorization, or temple practices, organized religion requires durable frameworks — and those frameworks become visible in social structures and material culture.

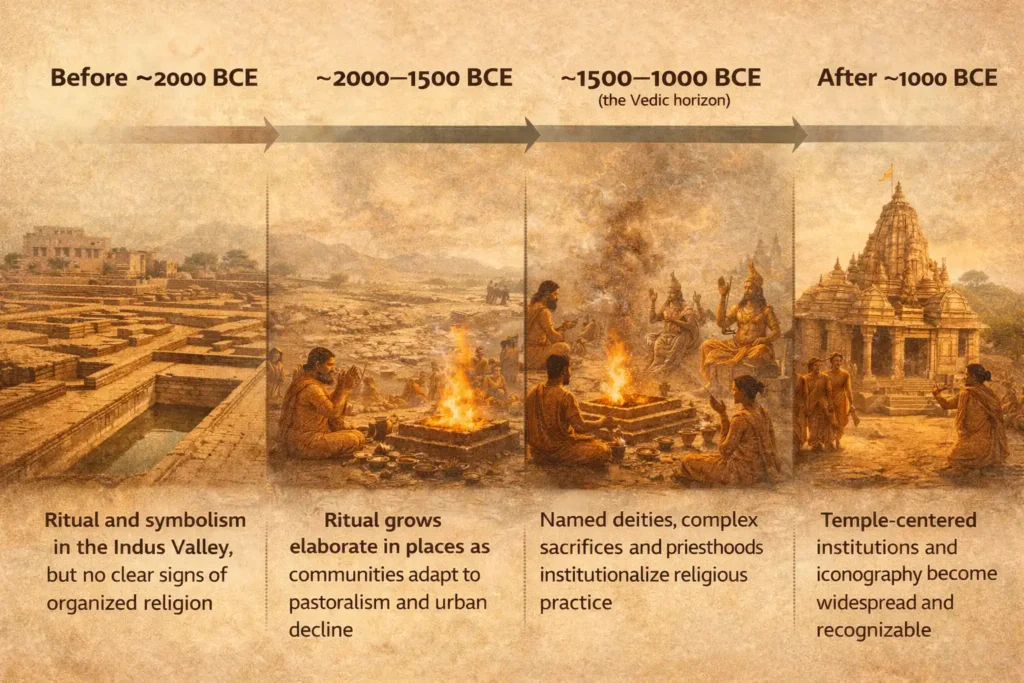

12. A short, evidence-led chronology (a synthesis)

To make sense of this long transformation, it helps to step back and view it as a gradual historical movement rather than a single turning point. What follows is a simplified timeline — not a rigid sequence, but a guide to how ritual life slowly took on religious form in the Indian subcontinent.

Before ~2000 BCE

Across much of the region, communities were rich in ritual and symbolism. In the cities of the Indus Valley, civic life was carefully organized around shared spaces, standardized practices, and symbolic acts. Yet there is little clear evidence of large temples, priestly hierarchies, or named gods dominating public life. Meaning appears embedded in daily practice rather than formalized religion.

~2000–1500 BCE

This period was marked by significant environmental and social change. Shifting river systems, climatic stress, and the decline of some urban centers reshaped how communities lived and moved. As populations adapted, ritual practices also evolved — becoming more elaborate in certain regions and more closely tied to emerging social authority. Religious expression was still fluid, but it was beginning to take on clearer structure.

~1500–1000 BCE (the Vedic horizon)

Here the evidence changes noticeably. We see the emergence of hymns addressed to specific deities, complex sacrificial rituals, and specialist priests trained to preserve and perform them. Religious knowledge becomes organized, transmitted across generations, and increasingly central to social life. This marks a key moment in the institutionalization of religion.

After ~1000 BCE

Over time, religious life became more visibly anchored in institutions. Temples grew in importance, iconography became standardized, and regional traditions began to interact and merge. What we recognize today as the broad religious landscape of later Indian history starts to take shape during this long phase of synthesis.

This timeline is necessarily simplified, but it captures the larger pattern: a slow movement from ritual abundance toward religion as a structured institution, shaped by environment, society, and historical encounter rather than by a single event or origin story.

13. Final reflection — a human story, not just an archaeological puzzle

Why should we care when and how religion entered Indian society? Because this is not a sterile timeline — it is the story of people seeking meaning in changing worlds.

Imagine a small community beside a river that’s drying, watching grain fail and markets shrink. Leaders stage a festival, orchestrate a sacrifice, recite old lines whose power seems to tether uncertain futures. Over generations, those lines become scripture; the families who guard them become authorities; ritual becomes the social mortar that holds groups together in uncertain times.

Religion, in this view, is not only metaphysics — it is a human technology for social survival, identity and authority. The Indus cities show us one way of organizing life; the later Vedic world shows us another. Each answer to “when” and “why” tells us something essential about how communities adapt to fragility, scale, and memory.

FAQ Questions – When Did Religion Enter Indian Society — And Why?

When did religion enter Indian society?

Religion, in its organized and institutional form, began to emerge gradually after the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization, becoming clearly visible during the Vedic period (c. 1500–1000 BCE). Earlier societies practiced ritual and symbolism, but without the temples, priesthoods, and canonical texts associated with organized religion.

Did the Indus Valley Civilization have a religion?

The Indus Valley shows strong evidence of ritual life and symbolism, but little clear evidence of organized religion. Archaeologists have not found large temples, named gods, or priestly hierarchies comparable to later traditions.

Read: Did the Indus Valley Civilization Have Religion?

Is Hinduism older than the Vedic period?

Elements that later shaped Hinduism—rituals, symbols, cosmological ideas—existed earlier, but Hinduism as a recognizable religious system formed over many centuries, especially after the Vedic age and well into the first millennium BCE.

Did invasions or migrations introduce religion to India?

Rather than a single invasion “bringing” religion, evidence suggests gradual cultural interaction, migration, and synthesis. Religious systems evolved through environmental change, social restructuring, and the blending of ritual traditions.

Why does this question still matter today?

Understanding when religion entered Indian society helps separate historical process from modern identity debates. It reminds us that religions are not timeless monoliths but evolving responses to human needs, environments, and power structures.

🎥 Watch the Video

Continue Reading History

History often reveals itself slowly—through patterns, pauses, and questions that refuse simple answers. If this exploration stayed with you, there are more essays waiting, tracing civilizations, ideas, and the human stories behind them.