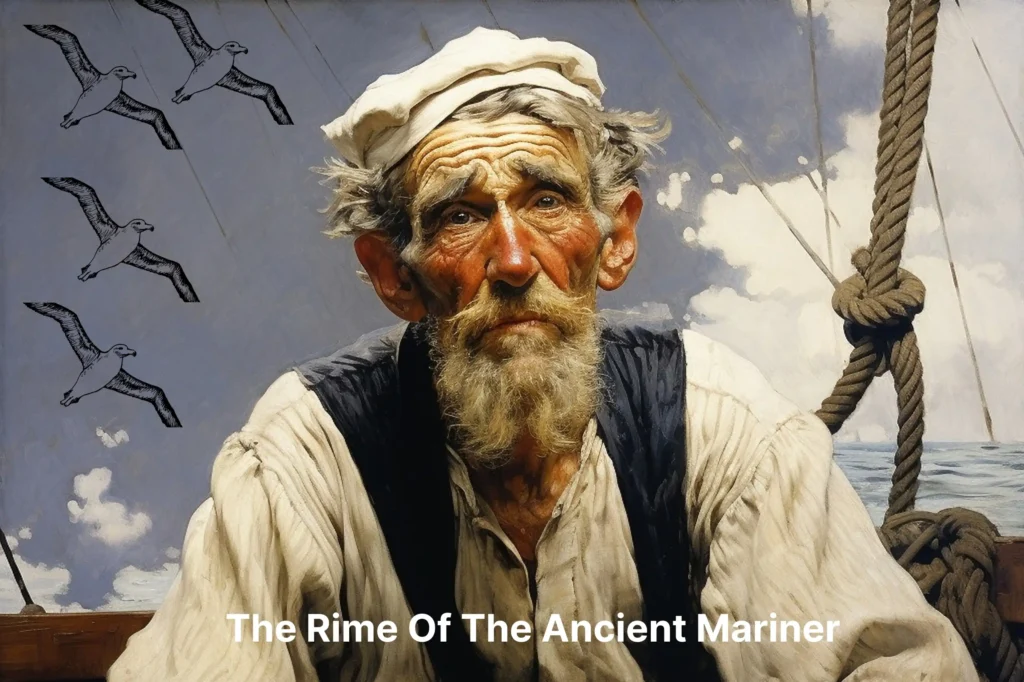

Introduction to ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’

Published in 1798, ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ is one of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s most celebrated works. This poem has left an indelible mark on English literature, influencing countless readers and writers with its haunting narrative and rich symbolism.

This poem is a part of: Lyrical Ballads a collection of poems by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. One of the other poems from: “Lyrical Ballads” written by: Samuel Taylor Coleridge is: The Foster Mother’s Tale Poem

The poem tells the story of an old mariner who recounts his harrowing sea voyage to a captivated wedding guest. Central to the plot is the mariner’s killing of an albatross, an act that brings a curse upon him and his shipmates. The poem explores themes of guilt, redemption, and the natural world, often using vivid and supernatural imagery to evoke a sense of mystery and foreboding.

Coleridge’s use of symbolism in ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ is profound. The albatross represents nature and the mariner’s crime against it, while the ghostly ship and spectral crew symbolize the consequences of his actions. The poem’s rich imagery, from the vast, desolate sea to the haunting figures that populate the mariner’s journey, creates a vivid and immersive reading experience.

‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ has had a lasting impact on literature and popular culture. Its themes and stylistic elements have been referenced and reinterpreted in various forms, from literary works to music and film. The poem continues to be studied and admired for its lyrical beauty and profound moral and philosophical questions.

Explore Our Category: English Poems

Read Poems by William Wordsworth

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Poem

Keywords: the rime of the ancient mariner, the rime of the ancient mariner summary, the rime of the ancient mariner explained, the rime of the ancient mariner pdf, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Poem,

Table of Contents

ARGUMENT

How a Ship having passed the Line was driven by Storms to the cold Country towards the South Pole; and how from thence she made her course to the tropical Latitude of the Great Pacific Ocean; and of the strange things that befell; and in what manner the Ancyent Marinere came back to his own Country.

~ Samuel Taylor Coleridge

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Part 1

THE RIME OF THE ANCYENT MARINERE

It is an ancyent Marinere,

~ Samuel Taylor Coleridge

And he stoppeth one of three:

“By thy long grey beard and thy glittering eye

“Now wherefore stoppest me?

“The Bridegroom’s doors are open’d wide

“And I am next of kin;

“The Guests are met, the Feast is set,—

“May’st hear the merry din.—

But still he holds the wedding-guest—

There was a Ship, quoth he—

“Nay, if thou’st got a laughsome tale,

“Marinere! come with me.”

He holds him with his skinny hand,

Quoth he, there was a Ship—

“Now get thee hence, thou grey-beard Loon!

“Or my Staff shall make thee skip.”

He holds him with his glittering eye—

The wedding guest stood still

And listens like a three year’s child;

The Marinere hath his will.

The wedding-guest sate on a stone,

He cannot chuse but hear:

And thus spake on that ancyent man,

The bright-eyed Marinere.

The Ship was cheer’d, the Harbour clear’d—

Merrily did we drop

Below the Kirk, below the Hill,

Below the Light-house top.

The Sun came up upon the left,

Out of the Sea came he:

And he shone bright, and on the right

Went down into the Sea.

Higher and higher every day,

Till over the mast at noon—

The wedding-guest here beat his breast,

For he heard the loud bassoon.

The Bride hath pac’d into the Hall,

Red as a rose is she;

Nodding their heads before her goes

The merry Minstralsy.

The wedding-guest he beat his breast,

Yet he cannot chuse but hear:

And thus spake on that ancyent Man,

The bright-eyed Marinere.

Listen, Stranger! Storm and Wind,

A Wind and Tempest strong!

For days and weeks it play’d us freaks—

Like Chaff we drove along.

Listen, Stranger! Mist and Snow,

And it grew wond’rous cauld:

And Ice mast-high came floating by

As green as Emerauld.

And thro’ the drifts the snowy clifts

Did send a dismal sheen;

Ne shapes of men ne beasts we ken—

The Ice was all between.

The Ice was here, the Ice was there,

The Ice was all around:

It crack’d and growl’d, and roar’d and howl’d—

Like noises of a swound.

At length did cross an Albatross,

Thorough the Fog it came;

And an it were a Christian Soul,

We hail’d it in God’s name.

The Marineres gave it biscuit-worms,

And round and round it flew:

The Ice did split with a Thunder-fit;

The Helmsman steer’d us thro’.

And a good south wind sprung up behind,

The Albatross did follow;

And every day for food or play

Came to the Marinere’s hollo!

In mist or cloud on mast or shroud

It perch’d for vespers nine,

Whiles all the night thro’ fog-smoke white

Glimmer’d the white moon-shine.

“God save thee, ancyent Marinere!

“From the fiends that plague thee thus—

“Why look’st thou so?”—with my cross bow

I shot the Albatross.

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Part 2

THE RIME OF THE ANCYENT MARINERE

The Sun came up upon the right,

Out of the Sea came he;

And broad as a weft upon the left

Went down into the Sea.

And the good south wind still blew behind,

But no sweet Bird did follow

Ne any day for food or play

Came to the Marinere’s hollo!

And I had done an hellish thing

And it would work ’em woe:

For all averr’d, I had kill’d the Bird

That made the Breeze to blow.

Ne dim ne red, like God’s own head,

The glorious Sun uprist:

Then all averr’d, I had kill’d the Bird

That brought the fog and mist.

’Twas right, said they, such birds to slay

That bring the fog and mist.

The breezes blew, the white foam flew,

The furrow follow’d free:

We were the first that ever burst

Into that silent Sea.

Down dropt the breeze, the Sails dropt down,

’Twas sad as sad could be

And we did speak only to break

The silence of the Sea.

All in a hot and copper sky

The bloody sun at noon,

Right up above the mast did stand,

No bigger than the moon.

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, ne breath ne motion,

As idle as a painted Ship

Upon a painted Ocean.

Water, water, every where

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where,

Ne any drop to drink.

The very deeps did rot: O Christ!

That ever this should be!

Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs

Upon the slimy Sea.

About, about, in reel and rout

The Death-fires danc’d at night;

The water, like a witch’s oils,

Burnt green and blue and white.

And some in dreams assured were

Of the Spirit that plagued us so:

Nine fathom deep he had follow’d us

From the Land of Mist and Snow.

And every tongue thro’ utter drouth

Was wither’d at the root;

We could not speak no more than if

We had been choked with soot.

Ah wel-a-day! what evil looks

Had I from old and young;

Instead of the Cross the Albatross

About my neck was hung.

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Part 3

THE RIME OF THE ANCYENT MARINERE

I saw a something in the Sky

No bigger than my fist;

At first it seem’d a little speck

And then it seem’d a mist:

It mov’d and mov’d, and took at last

A certain shape, I wist.

A speck, a mist, a shape, I wist!

And still it ner’d and ner’d;

And, an it dodg’d a water-sprite,

It plung’d and tack’d and veer’d.

With throat unslack’d, with black lips bak’d

Ne could we laugh, ne wail:

Then while thro’ drouth all dumb they stood

I bit my arm and suck’d the blood

And cry’d, A sail! a sail!

With throat unslack’d, with black lips bak’d

Agape they hear’d me call:

Gramercy! they for joy did grin

And all at once their breath drew in

As they were drinking all.

She doth not tack from side to side—

Hither to work us weal

Withouten wind, withouten tide

She steddies with upright keel.

The western wave was all a flame,

The day was well nigh done!

Almost upon the western wave

Rested the broad bright Sun;

When that strange shape drove suddenly

Betwixt us and the Sun.

And strait the Sun was fleck’d with bars

(Heaven’s mother send us grace)

As if thro’ a dungeon grate he peer’d

With broad and burning face.

Alas! (thought I, and my heart beat loud)

How fast she neres and neres!

Are those her Sails that glance in the Sun

Like restless gossameres?

Are these her naked ribs, which fleck’d

The sun that did behind them peer?

And are these two all, all the crew,

That woman and her fleshless Pheere?

His bones were black with many a crack,

All black and bare, I ween;

Jet-black and bare, save where with rust

Of mouldy damps and charnel crust

They’re patch’d with purple and green.

Her lips are red, her looks are free,

Her locks are yellow as gold:

Her skin is as white as leprosy,

And she is far liker Death than he;

Her flesh makes the still air cold.

The naked Hulk alongside came

And the Twain were playing dice;

“The Game is done! I’ve won, I’ve won!”

Quoth she, and whistled thrice.

A gust of wind sterte up behind

And whistled thro’ his bones;

Thro’ the holes of his eyes and the hole of his mouth

Half-whistles and half-groans.

With never a whisper in the Sea

Off darts the Spectre-ship;

While clombe above the Eastern bar

The horned Moon, with one bright Star

Almost atween the tips.

One after one by the horned Moon

(Listen, O Stranger! to me)

Each turn’d his face with a ghastly pang

And curs’d me with his ee.

Four times fifty living men,

With never a sigh or groan,

With heavy thump, a lifeless lump

They dropp’d down one by one.

Their souls did from their bodies fly,—

They fled to bliss or woe;

And every soul it pass’d me by,

Like the whiz of my Cross-bow.

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Part 4

THE RIME OF THE ANCYENT MARINERE

“I fear thee, ancyent Marinere!

“I fear thy skinny hand;

“And thou art long and lank and brown

“As is the ribb’d Sea-sand.

“I fear thee and thy glittering eye

“And thy skinny hand so brown”—

Fear not, fear not, thou wedding guest!

This body dropt not down.

Alone, alone, all all alone

Alone on the wide wide Sea;

And Christ would take no pity on

My soul in agony.

The many men so beautiful,

And they all dead did lie!

And a million million slimy things

Liv’d on—and so did I.

I look’d upon the rotting Sea,

And drew my eyes away;

I look’d upon the eldritch deck,

And there the dead men lay.

I look’d to Heaven, and try’d to pray;

But or ever a prayer had gusht,

A wicked whisper came and made

My heart as dry as dust.

I clos’d my lids and kept them close,

Till the balls like pulses beat;

For the sky and the sea, and the sea and the sky

Lay like a load on my weary eye,

And the dead were at my feet.

The cold sweat melted from their limbs,

Ne rot, ne reek did they;

The look with which they look’d on me,

Had never pass’d away.

An orphan’s curse would drag to Hell

A spirit from on high:

But O! more horrible than that

Is the curse in a dead man’s eye!

Seven days, seven nights I saw that curse

And yet I could not die.

The moving Moon went up the sky

And no where did abide:

Softly she was going up

And a star or two beside—

Her beams bemock’d the sultry main

Like morning frosts yspread;

But where the ship’s huge shadow lay,

The charmed water burnt alway

A still and awful red.

Beyond the shadow of the ship

I watch’d the water-snakes:

They mov’d in tracks of shining white;

And when they rear’d, the elfish light

Fell off in hoary flakes.

Within the shadow of the ship

I watch’d their rich attire:

Blue, glossy green, and velvet black

They coil’d and swam; and every track

Was a flash of golden fire.

O happy living things! no tongue

Their beauty might declare:

A spring of love gusht from my heart,

And I bless’d them unaware!

Sure my kind saint took pity on me,

And I bless’d them unaware.

The self-same moment I could pray;

And from my neck so free

The Albatross fell off, and sank

Like lead into the sea.

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Part 5

THE RIME OF THE ANCYENT MARINERE

O sleep, it is a gentle thing

Belov’d from pole to pole!

To Mary-queen the praise be yeven

She sent the gentle sleep from heaven

That slid into my soul.

The silly buckets on the deck

That had so long remain’d,

I dreamt that they were fill’d with dew

And when I awoke it rain’d.

My lips were wet, my throat was cold,

My garments all were dank;

Sure I had drunken in my dreams

And still my body drank.

I mov’d and could not feel my limbs,

I was so light, almost

I thought that I had died in sleep,

And was a blessed Ghost.

The roaring wind! it roar’d far off,

It did not come anear;

But with its sound it shook the sails

That were so thin and sere.

The upper air bursts into life,

And a hundred fire-flags sheen

To and fro they are hurried about;

And to and fro, and in and out

The stars dance on between.

The coming wind doth roar more loud;

The sails do sigh, like sedge:

The rain pours down from one black cloud

And the Moon is at its edge.

Hark! hark! the thick black cloud is cleft,

And the Moon is at its side:

Like waters shot from some high crag,

The lightning falls with never a jag

A river steep and wide.

The strong wind reach’d the ship: it roar’d

And dropp’d down, like a stone!

Beneath the lightning and the moon

The dead men gave a groan.

They groan’d, they stirr’d, they all uprose,

Ne spake, ne mov’d their eyes:

It had been strange, even in a dream

To have seen those dead men rise.

The helmsman steerd, the ship mov’d on;

Yet never a breeze up-blew;

The Marineres all ’gan work the ropes,

Where they were wont to do:

They rais’d their limbs like lifeless tools—

We were a ghastly crew.

The body of my brother’s son

Stood by me knee to knee:

The body and I pull’d at one rope,

But he said nought to me—

And I quak’d to think of my own voice

How frightful it would be!

The day-light dawn’d—they dropp’d their arms,

And cluster’d round the mast:

Sweet sounds rose slowly thro’ their mouths

And from their bodies pass’d.

Around, around, flew each sweet sound,

Then darted to the sun:

Slowly the sounds came back again

Now mix’d, now one by one.

Sometimes a dropping from the sky

I heard the Lavrock sing;

Sometimes all little birds that are

How they seem’d to fill the sea and air

With their sweet jargoning,

And now ’twas like all instruments,

Now like a lonely flute;

And now it is an angel’s song

That makes the heavens be mute.

It ceas’d: yet still the sails made on

A pleasant noise till noon,

A noise like of a hidden brook

In the leafy month of June,

That to the sleeping woods all night

Singeth a quiet tune.

Listen, O listen, thou Wedding-guest!

“Marinere! thou hast thy will:

“For that, which comes out of thine eye, doth make

“My body and soul to be still.”

Never sadder tale was told

To a man of woman born:

Sadder and wiser thou wedding-guest!

Thou’lt rise to morrow morn.

Never sadder tale was heard

By a man of woman born:

The Marineres all return’d to work

As silent as beforne.

The Marineres all ’gan pull the ropes,

But look at me they n’old:

Thought I, I am as thin as air—

They cannot me behold.

Till noon we silently sail’d on

Yet never a breeze did breathe:

Slowly and smoothly went the ship

Mov’d onward from beneath.

Under the keel nine fathom deep

From the land of mist and snow

The spirit slid: and it was He

That made the Ship to go.

The sails at noon left off their tune

And the Ship stood still also.

The sun right up above the mast

Had fix’d her to the ocean:

But in a minute she ’gan stir

With a short uneasy motion—

Backwards and forwards half her length

With a short uneasy motion.

Then, like a pawing horse let go,

She made a sudden bound:

It flung the blood into my head,

And I fell into a swound.

How long in that same fit I lay,

I have not to declare;

But ere my living life return’d,

I heard and in my soul discern’d

Two voices in the air,

“Is it he?” quoth one, “Is this the man?

“By him who died on cross,

“With his cruel bow he lay’d full low

“The harmless Albatross.

“The spirit who ’bideth by himself

“In the land of mist and snow,

“He lov’d the bird that lov’d the man

“Who shot him with his bow.”

The other was a softer voice,

As soft as honey-dew:

Quoth he the man hath penance done,

And penance more will do.

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Part 6

THE RIME OF THE ANCYENT MARINERE

FIRST VOICE.

“But tell me, tell me! speak again,

“Thy soft response renewing—

“What makes that ship drive on so fast?

“What is the Ocean doing?”

SECOND VOICE.

“Still as a Slave before his Lord,

“The Ocean hath no blast:

“His great bright eye most silently

“Up to the moon is cast—

“If he may know which way to go,

“For she guides him smooth or grim.

“See, brother, see! how graciously

“She looketh down on him.”

FIRST VOICE.

“But why drives on that ship so fast

“Withouten wave or wind?”

SECOND VOICE.

“The air is cut away before,

“And closes from behind.

“Fly, brother, fly! more high, more high,

“Or we shall be belated:

“For slow and slow that ship will go,

“When the Marinere’s trance is abated.”

I woke, and we were sailing on

As in a gentle weather:

’Twas night, calm night, the moon was high;

The dead men stood together.

All stood together on the deck,

For a charnel-dungeon fitter:

All fix’d on me their stony eyes

That in the moon did glitter.

The pang, the curse, with which they died,

Had never pass’d away:

I could not draw my een from theirs

Ne turn them up to pray.

And in its time the spell was snapt,

And I could move my een:

I look’d far-forth, but little saw

Of what might else be seen.

Like one, that on a lonely road

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turn’d round, walks on

And turns no more his head:

Because he knows, a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread.

But soon there breath’d a wind on me,

Ne sound ne motion made:

Its path was not upon the sea

In ripple or in shade.

It rais’d my hair, it fann’d my cheek,

Like a meadow-gale of spring—

It mingled strangely with my fears,

Yet it felt like a welcoming.

Swiftly, swiftly flew the ship,

Yet she sail’d softly too:

Sweetly, sweetly blew the breeze—

On me alone it blew.

O dream of joy! is this indeed

The light-house top I see?

Is this the Hill? Is this the Kirk?

Is this mine own countrée?

We drifted o’er the Harbour-bar,

And I with sobs did pray—

“O let me be awake, my God!

“Or let me sleep alway!”

The harbour-bay was clear as glass,

So smoothly it was strewn!

And on the bay the moon light lay,

And the shadow of the moon.

The moonlight bay was white all o’er,

Till rising from the same,

Full many shapes, that shadows were,

Like as of torches came.

A little distance from the prow

Those dark-red shadows were;

But soon I saw that my own flesh

Was red as in a glare.

I turn’d my head in fear and dread,

And by the holy rood,

The bodies had advanc’d, and now

Before the mast they stood.

They lifted up their stiff right arms,

They held them strait and tight;

And each right-arm burnt like a torch,

A torch that’s borne upright.

Their stony eye-balls glitter’d on

In the red and smoky light.

I pray’d and turn’d my head away

Forth looking as before.

There was no breeze upon the bay,

No wave against the shore.

The rock shone bright, the kirk no less

That stands above the rock:

The moonlight steep’d in silentness

The steady weathercock.

And the bay was white with silent light,

Till rising from the same

Full many shapes, that shadows were,

In crimson colours came.

A little distance from the prow

Those crimson shadows were:

I turn’d my eyes upon the deck—

O Christ! what saw I there?

Each corse lay flat, lifeless and flat;

And by the Holy rood

A man all light, a seraph-man,

On every corse there stood.

This seraph-band, each wav’d his hand:

It was a heavenly sight:

They stood as signals to the land,

Each one a lovely light:

This seraph-band, each wav’d his hand,

No voice did they impart—

No voice; but O! the silence sank,

Like music on my heart.

Eftsones I heard the dash of oars,

I heard the pilot’s cheer:

My head was turn’d perforce away

And I saw a boat appear.

Then vanish’d all the lovely lights;

The bodies rose anew:

With silent pace, each to his place,

Came back the ghastly crew.

The wind, that shade nor motion made,

On me alone it blew.

The pilot, and the pilot’s boy

I heard them coming fast:

Dear Lord in Heaven! it was a joy,

The dead men could not blast.

I saw a third—I heard his voice:

It is the Hermit good!

He singeth loud his godly hymns

That he makes in the wood.

He’ll shrieve my soul, he’ll wash away

The Albatross’s blood.

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Part 7

THE RIME OF THE ANCYENT MARINERE

This Hermit good lives in that wood

Which slopes down to the Sea.

How loudly his sweet voice he rears!

He loves to talk with Marineres

That come from a far Contrée.

He kneels at morn and noon and eve—

He hath a cushion plump:

It is the moss, that wholly hides

The rotted old Oak-stump.

The Skiff-boat ne’rd: I heard them talk,

“Why, this is strange, I trow!

“Where are those lights so many and fair

“That signal made but now?

“Strange, by my faith!” the Hermit said—

“And they answer’d not our cheer.

“The planks look warp’d, and see those sails

“How thin they are and sere!

“I never saw aught like to them

“Unless perchance it were

“The skeletons of leaves that lag

“My forest brook along:

“When the Ivy-tod is heavy with snow,

“And the Owlet whoops to the wolf below

“That eats the she-wolf’s young.

“Dear Lord! it has a fiendish look”—

(The Pilot made reply)

“I am a-fear’d.—“Push on, push on!”

Said the Hermit cheerily.

The Boat came closer to the Ship,

But I ne spake ne stirr’d!

The Boat came close beneath the Ship,

And strait a sound was heard!

Under the water it rumbled on,

Still louder and more dread:

It reach’d the Ship, it split the bay;

The Ship went down like lead.

Stunn’d by that loud and dreadful sound,

Which sky and ocean smote:

Like one that hath been seven days drown’d

My body lay afloat:

But, swift as dreams, myself I found

Within the Pilot’s boat.

Upon the whirl, where sank the Ship,

The boat spun round and round:

And all was still, save that the hill

Was telling of the sound.

I mov’d my lips: the Pilot shriek’d

And fell down in a fit.

The Holy Hermit rais’d his eyes

And pray’d where he did sit.

I took the oars: the Pilot’s boy,

Who now doth crazy go,

Laugh’d loud and long, and all the while

His eyes went to and fro,

“Ha! ha!” quoth he—“full plain I see,

“The devil knows how to row.”

And now all in mine own Countrée

I stood on the firm land!

The Hermit stepp’d forth from the boat,

And scarcely he could stand.

“O shrieve me, shrieve me, holy Man!”

The Hermit cross’d his brow—

“Say quick,” quoth he, “I bid thee say

“What manner man art thou?”

Forthwith this frame of mine was wrench’d

With a woeful agony,

Which forc’d me to begin my tale

And then it left me free.

Since then at an uncertain hour,

Now oftimes and now fewer,

That anguish comes and makes me tell

My ghastly aventure.

I pass, like night, from land to land;

I have strange power of speech;

The moment that his face I see

I know the man that must hear me;

To him my tale I teach.

What loud uproar bursts from that door!

The Wedding-guests are there;

But in the Garden-bower the Bride

And Bride-maids singing are:

And hark the little Vesper-bell

Which biddeth me to prayer.

O Wedding-guest! this soul hath been

Alone on a wide wide sea:

So lonely ’twas, that God himself

Scarce seemed there to be.

O sweeter than the Marriage-feast,

’Tis sweeter far to me

To walk together to the Kirk

With a goodly company.

To walk together to the Kirk

And all together pray,

While each to his great father bends,

Old men, and babes, and loving friends,

And Youths, and Maidens gay.

Farewell, farewell! but this I tell

To thee, thou wedding-guest!

He prayeth well who loveth well

Both man and bird and beast.

He prayeth best who loveth best,

All things both great and small:

For the dear God, who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.

The Marinere, whose eye is bright,

Whose beard with age is hoar,

Is gone; and now the wedding-guest

Turn’d from the bridegroom’s door.

He went, like one that hath been stunn’d

And is of sense forlorn:

A sadder and a wiser man

He rose the morrow morn.

Poem Source: The Project Gutenberg eBook of Lyrical Ballads 1798, by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Keywords: the rime of the ancient mariner, the rime of the ancient mariner summary, the rime of the ancient mariner explained, the rime of the ancient mariner pdf, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Poem,

The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner summary

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Explained

THE RIME OF THE ANCYENT MARINERE

The poem begins with an eerie and compelling scene: an old mariner stops a wedding guest to recount his harrowing tale. This setting immediately introduces a sense of foreboding and mystery. The wedding, symbolizing joy and new beginnings, contrasts sharply with the mariner’s ominous presence. The reader is drawn into the mariner’s world, filled with dark and supernatural elements, setting the tone for the gripping narrative that follows. As the mariner begins his tale, the audience is enveloped in an atmosphere of suspense and anticipation, eager to unravel the enigmatic events that took place on the ill-fated voyage.

The Mariner’s Tale: The Journey and the Albatross

THE RIME OF THE ANCYENT MARINERE

The Ancient Mariner begins his tale by recounting the initial stages of his sea voyage. The journey starts under auspicious conditions, with the ship sailing smoothly and the crew in high spirits. However, this period of calm is short-lived as the ship soon encounters a severe storm. The tempest is relentless, driving the vessel southward into the frigid and desolate Antarctic waters. The crew battles the elements, facing the harrowing cold and treacherous ice.

In the midst of this icy expanse, hope arrives in the form of an albatross. The bird appears mysteriously, circling the ship and leading it through the perilous ice fields. The crew welcomes the albatross, seeing it as a good omen. The bird’s presence brings a sense of relief and awe, as it seems to guide the ship to safety, away from the clutches of the Antarctic.

However, this sense of reprieve is shattered by an inexplicable act. The Ancient Mariner, driven by an unfathomable impulse, kills the albatross with his crossbow. This senseless act of violence against a creature of nature marks a turning point in the voyage. The immediate aftermath is one of confusion and horror among the crew, as they grapple with the Mariner’s inexplicable deed.

The killing of the albatross quickly brings dire consequences upon the crew. The ship is beset by misfortunes, and the once-favorable winds cease, leaving the vessel stagnant in the water. The crew faces supernatural retribution, as they endure mysterious and terrifying experiences. The albatross, now a symbol of their doom, is hung around the Mariner’s neck by his shipmates, signifying the burden of guilt he must carry.

This episode underscores the theme of nature and the supernatural in ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.’ The Mariner’s thoughtless act against the albatross, a creature personifying the natural world, invokes a supernatural response. The crew’s subsequent suffering serves as a poignant reminder of the interconnectedness of humanity and nature, and the severe repercussions that can arise from disrupting this delicate balance.

The Consequences: Despair and Redemption

THE RIME OF THE ANCYENT MARINERE

The aftermath of the mariner’s fateful decision to kill the albatross is catastrophic. The ship and its crew are soon plunged into a series of dire supernatural events. A curse befalls them, manifesting in the form of relentless hardships. The once favorable wind ceases, leaving the vessel stranded in a motionless sea. The crew suffers from severe thirst and hunger, exacerbated by the oppressive heat and lack of fresh water. Their dire conditions intensify as ghostly figures, Death and Life-in-Death, appear in a spectral ship. These entities cast lots for the souls of the mariners, with Life-in-Death winning the soul of the ancient mariner.

The crew’s suffering reaches a zenith as they succumb one by one to the curse, dying in agony and leaving the mariner as the sole survivor. His isolation is profound, marked by the heavy weight of guilt and remorse. The dead crew, with their eyes open in silent reproach, only deepen his torment. The mariner is subjected to a prolonged period of extreme solitude and reflection, with the albatross hung around his neck as a symbol of his guilt and the curse he brought upon them.

Amidst this despair, a pivotal transformation occurs. The mariner, in his profound isolation, begins to observe the natural world around him. His perception shifts as he starts to see the inherent beauty in the simplest forms of life. This newfound appreciation culminates in a moment of spiritual awakening when he blesses the water-snakes, recognizing them as beautiful creations. This act of genuine appreciation and respect for nature marks the breaking of the curse. The albatross falls from his neck, symbolizing the lifting of his burden. This moment signifies the beginning of his redemption, as he learns to value the interconnectedness of all living things and the importance of respect for nature.

The Return and the Moral Lesson

THE RIME OF THE ANCYENT MARINERE

Upon returning to his homeland, the Ancient Mariner is rescued by a hermit, a pilot, and the pilot’s boy. This moment of rescue is not just a physical salvation but also a spiritual one, symbolizing a chance for the Mariner’s redemption. However, the Mariner’s journey does not end with his return. He is compelled to share his harrowing tale with others as a form of penance, driven by an uncontrollable urge to recount his experiences. This need to narrate his story signifies a deeper moral obligation to spread the lessons he has learned.

The Mariner’s interaction with the wedding guest serves as a pivotal moment in the poem. The wedding guest, initially impatient and dismissive, becomes captivated and profoundly affected by the Mariner’s tale. This transformation underscores the power of storytelling and the profound impact that the Mariner’s experiences have on those who hear them. The wedding guest leaves the encounter a “sadder and a wiser man,” illustrating the poem’s ability to evoke reflection and change in its audience.

The overarching moral lessons of ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ are profound and multifaceted. One of the central themes is the respect for nature. The Mariner’s senseless killing of the albatross, a symbol of nature’s innocence and beauty, sets off a chain of dire consequences, highlighting the interconnectedness of all living things and the importance of respecting the natural world. Additionally, the poem delves into the consequences of one’s actions, illustrating how a single thoughtless act can lead to irreversible repercussions.

Yet, amidst these themes of consequence and suffering, there is also a powerful message of redemption. The Mariner’s journey, though fraught with hardship, ultimately leads to a profound spiritual awakening and a chance for atonement. This theme of redemption resonates deeply, suggesting that while mistakes are inevitable, the possibility for forgiveness and transformation remains.

‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ continues to be relevant in contemporary discussions about humanity and the environment. Its themes of respect for nature, the far-reaching consequences of human actions, and the potential for redemption are timeless, offering valuable insights into our relationship with the world around us. The enduring legacy of this poem lies in its ability to speak to universal truths and inspire ongoing reflection and dialogue.

Conclusion: THE RIME OF THE ANCYENT MARINERE

In conclusion, ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ remains a seminal work in the canon of English literature. Coleridge’s masterful use of narrative, symbolism, and imagery ensures that this poem will continue to captivate and inspire future generations of readers.

The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner pdf

Keywords: the rime of the ancient mariner, the rime of the ancient mariner summary, the rime of the ancient mariner explained, the rime of the ancient mariner pdf, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Poem,